I recently subscribed to The Met on YouTube and found a trove of treasures from this institutional mainstay. Since 2020, the museum has released three to four films from the moving-image archive to celebrate its 150th anniversary. Called “From The Vaults,” the series continues through March 2022.

Hey, when you turn 150 years old, it’s your party and you can make everyone celebrate for two years if you want to.

I’m slowly making my way through all the artifacts they’ve posted; most recently, a 1992 film about American painter Ralph Fasanella, who was known for his depictions of working-class city life and born in the Bronx on Labor Day 1914 to newly minted Italian immigrants.

Berenice Abbott: “A View of the 20th Century”

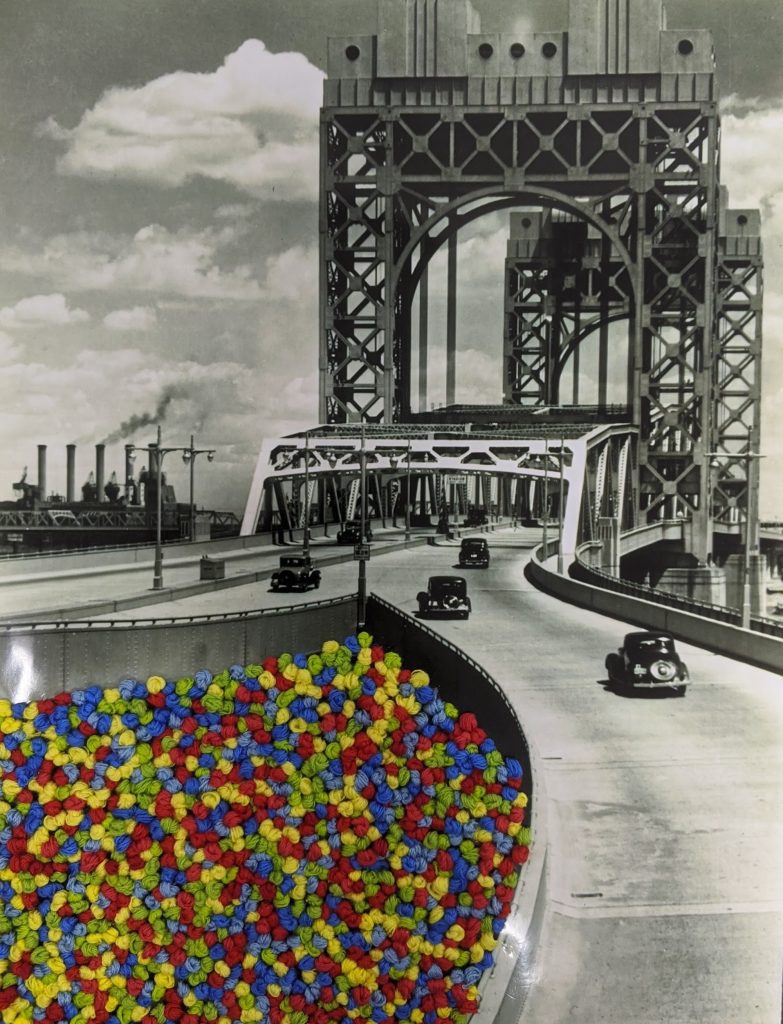

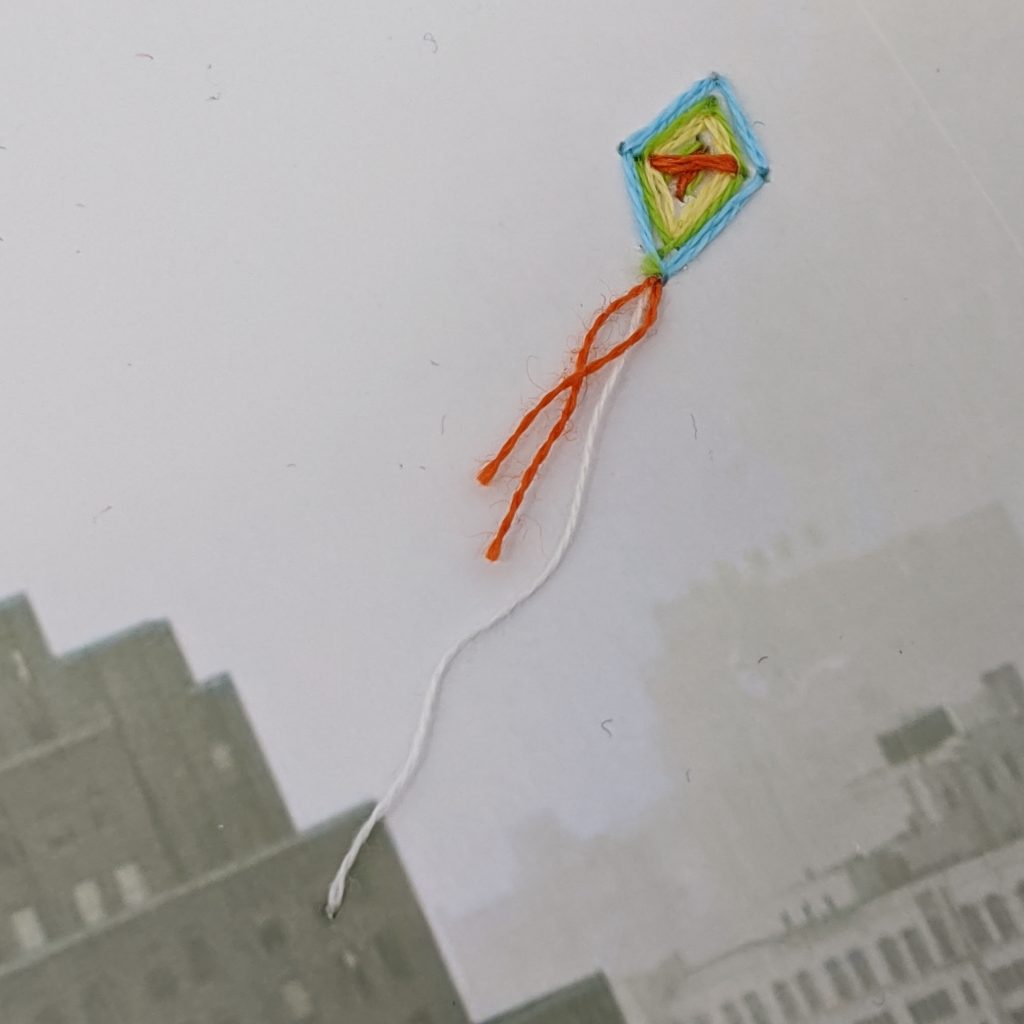

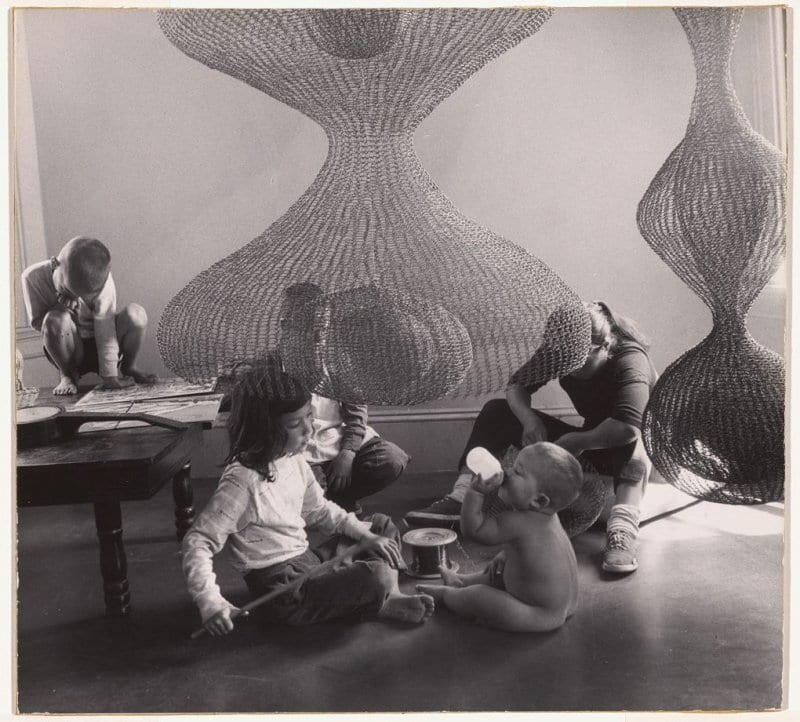

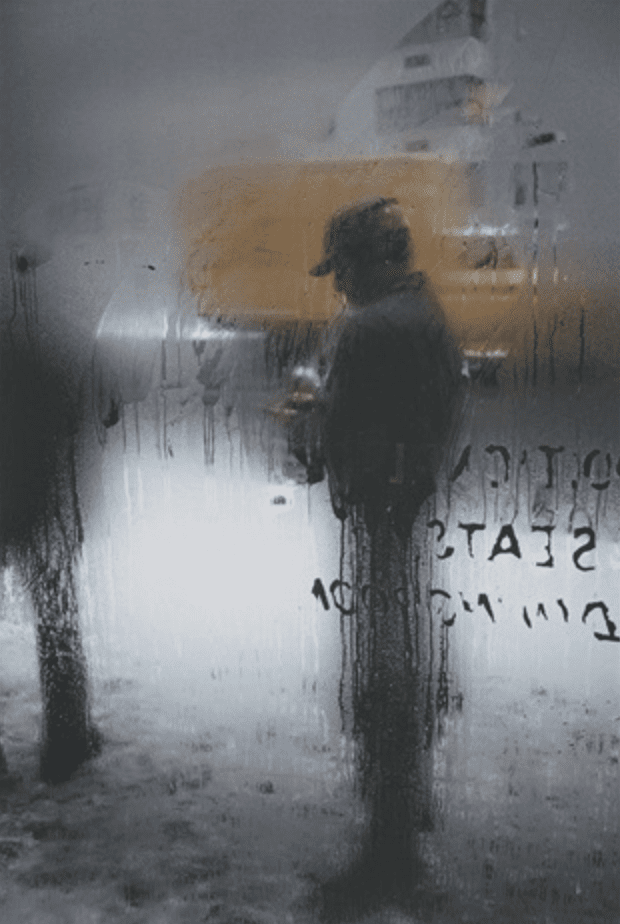

One of the most compelling docs I’ve watched in The Met’s series so far was another 1992 piece, this one about the photographer Berenice Abbott. I LOVE Berenice and am often drawn to her Works Progress Administration images when selecting images for my embroidery collection.

As one source in the film so succinctly put it, Berenice took, “Emotionally resonant pictures of ordinary things.” That’s as working class as it comes.

What I didn’t realize was how accomplished Berenice was in other intellectual and theoretical pursuits beyond artmaking. Here are some of my favorite quotes from this legendary artist.

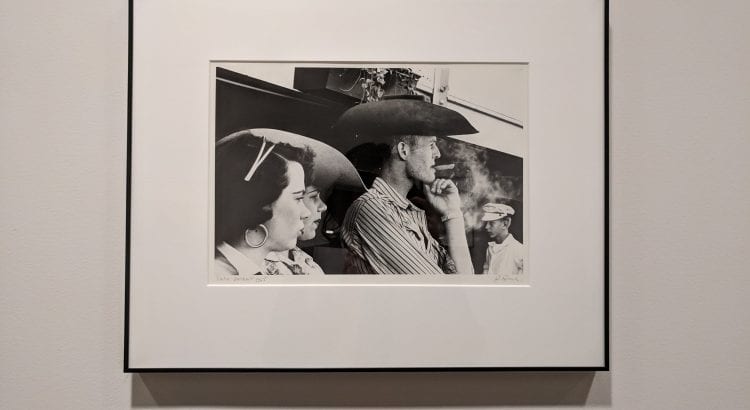

“This clear-eyed, insightful documentary, directed by Martha Wheelock and Kay Weaver, offers a grand tour of Abbott’s extraordinary life, from her youth in Ohio and apprenticeship in Paris through her later groundbreaking scientific photography at MIT and final years in Maine.

Using the artist’s memories as a lens for apprehending nearly a century of American and European cultural history, this film pays homage to Abbott’s genius for invention, her free-spirited embrace of uncertainty and experience, and her unshakeable devotion the art of photography.”

Watch Berenice Abbott: A View of the 20th Century

Best Berenice Abbott quotes

in “A View of the 20th Century”

Berenice Abbott photographing on South Street, New York, 1937. Photo by Consuelo Kanaga.

ON BEING AN ARTIST

“The only pleasure you can get from creating something is the pleasure you have in doing it. Not the final product even. The pleasure you have in doing it. And that cannot be taken away from you. And it cannot be crushed. But you had a certain kind of joy creating it. And that’s all you can expect.”

“There are many teachers who could ruin you. Before you know it you could be a pale copy of this teacher or that teacher. You have to evolve on your own.”

“I think you have to be intensely personal and be true to yourself. The subject matter that excites you is something you want to photograph. You have to convey to the person who looks at it what it was that excited you.”

ON ART

“If you’re trying to express people, you have to be part of it because it’s an exchange. You’re a part of that time.”

“The art is selecting what is worthwhile to take the trouble about.”

“I think it stands to reason that if you recognize and appreciate your heritage, it helps you with your future.”

ON PHOTOGRAPHY

“Anything you photograph has to be exciting somehow visually. It has to be photographically important, visually important. Otherwise you write about it.”

“Photography is very much a prisoner of its time. You work within the framework of the technique at the time, and that’s the way you have to judge photography.”

“I think all photography is documentary or it isn’t even photography. Most photographs are documents by their very nature of the realistic image. When they try to make it a nonrealistic image, they’re imitating another medium. Selectivity is key.”

“Many interesting things aren’t photogenic at all.”

ON CITY APPEAL

“It isn’t just that you think the city is beautiful. It’s that the city is very interesting. Everything in it has been built by man. It expresses people more than people themselves.”

“The city is full of every period, every epoch. Everything there comes out of the human gut. Everything that’s built. Every sign that’s put up. The new, the old, the beautiful, the ugly. It’s the juxtaposition of all this that is an intensely, immensely human subject. You’re photographing people when you’re photographing a city. You don’t have to have a person in it.”

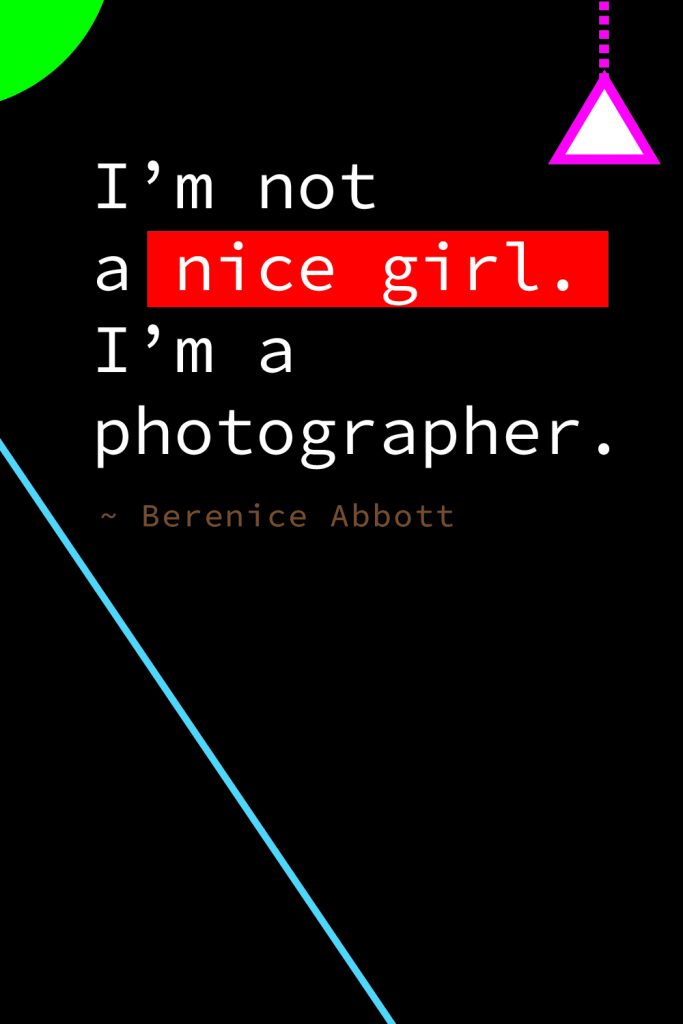

ON BEING A WOMAN

“He said, ‘Nice girls don’t go down on the Bowery.” And I said, ‘Well, I’m not a nice girl. I’m a photographer.‘”

“My assistant got the job. A young man whom I had trained. I think the last thing the world really wants are independent women. I don’t think they like independent women much. Just why I don’t know. But I don’t care.”

“Yes, I’ve always been a loner. I’m certain that some people marry and it doesn’t spoil their independence, even women in some cases. The vast majority seems to snare the woman and she can lose track of her directions and her desires and her interests. I’ve heard so many women say, ‘Oh I would like to have done this but after all my family came first. I had to look after my sons.’ So apparently that was more important to them. To me it would be like losing yourself. I think your work is the most important thing in your life. To spend more time with it.”

ON BEING

“I believe in nature and truth and common sense, pursuit of knowledge. Nothing is any good unless you sort of live up to it. Do unto others as you would have done unto you. That is very valid and can’t get you into any trouble. But you don’t need religion to have morals.”

“I always thought that there was nothing smarter than an old woman. You’ve lived so much, you’ve seen so much, in some sense you’ve been on the passive end of it, which means that you have observed plenty. But my impression was always that most ordinary women, if they’re old, have some remarkable quality that no other people have.”

“I had no idea I was getting older. I’ve never worried about getting older. I don’t see why people make so much of a thing about aging. It’s so natural to age. Everything is aging all the time. Everybody’s aging constantly. Why worry? It’s slow. You’re not aware of it.You just take it in your stride. But women are so harassed with the idea because of the social attitude, the unfairness of social attitudes between the aging of men and women is so ridiculous and so dreadful that women’s years seem to be only good as long as she can procreate, but a man can be very attractive at 80.”

“I’m planning to live to be 102.” 🙂