Show Your Work

2019

See all my work from this series on Instagram @jackiemanteydotcom

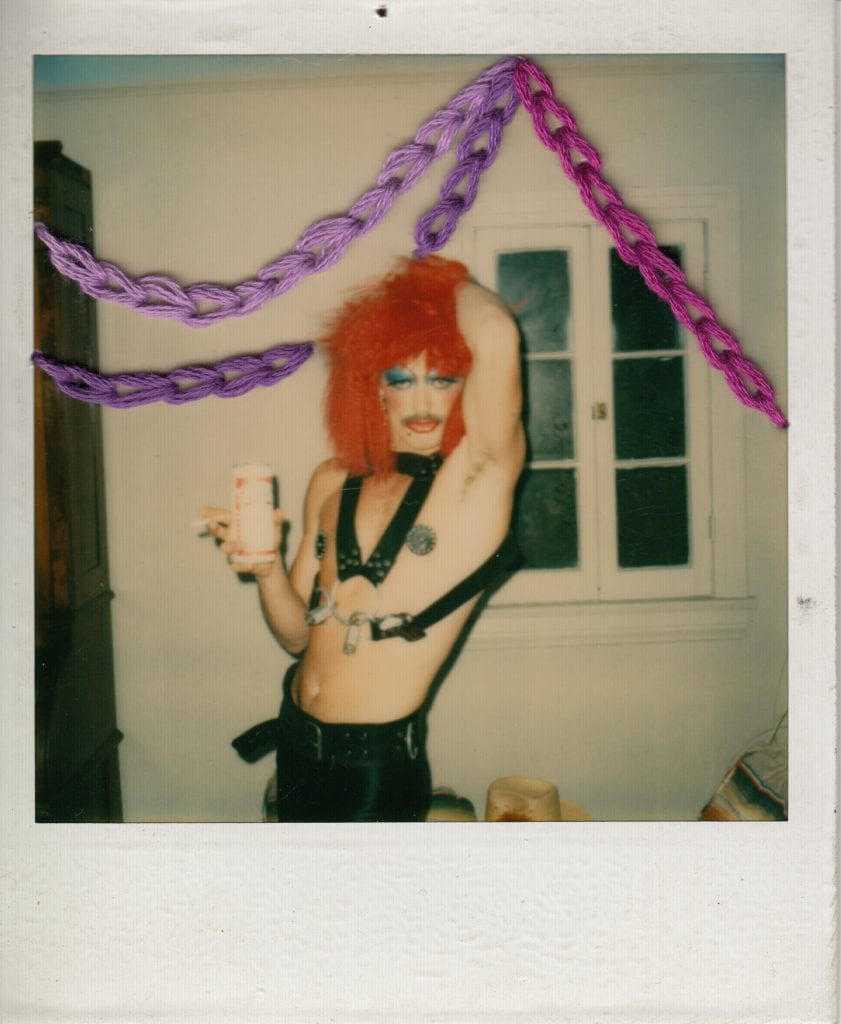

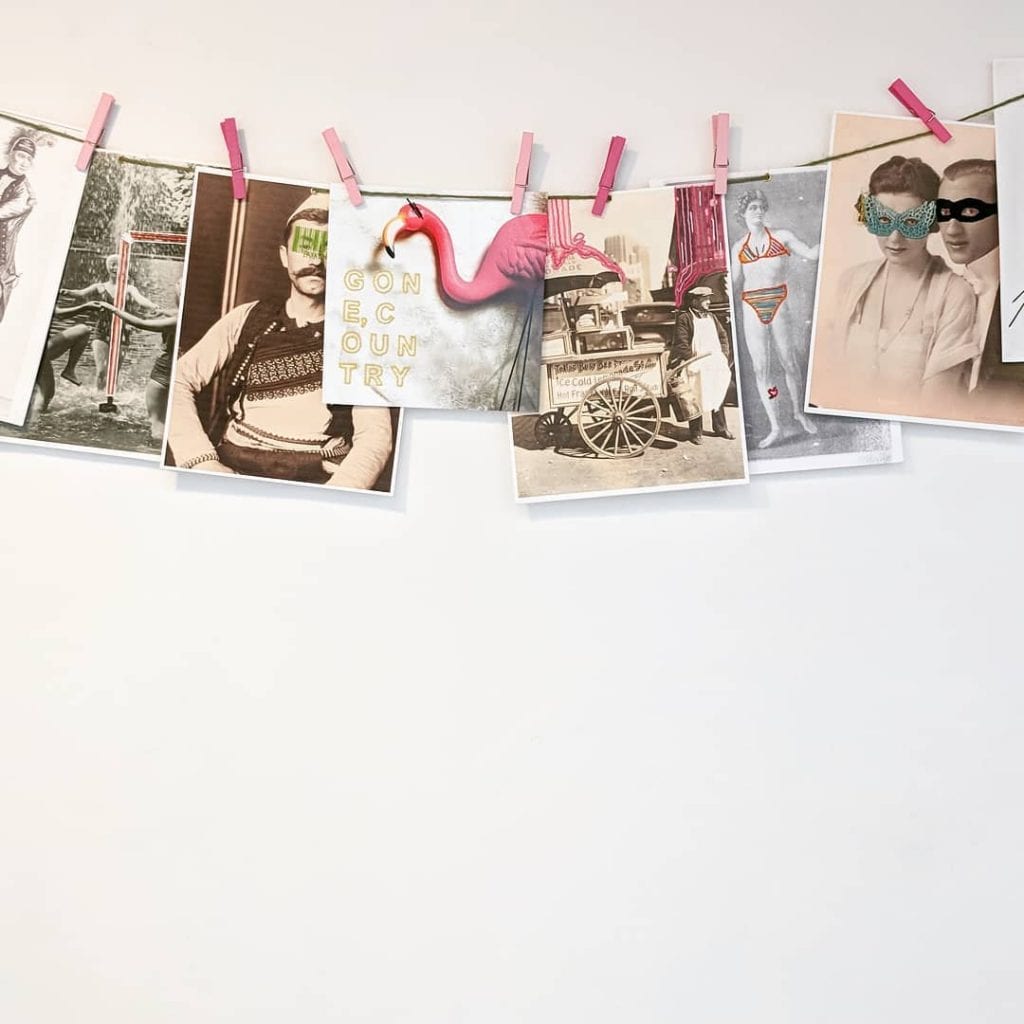

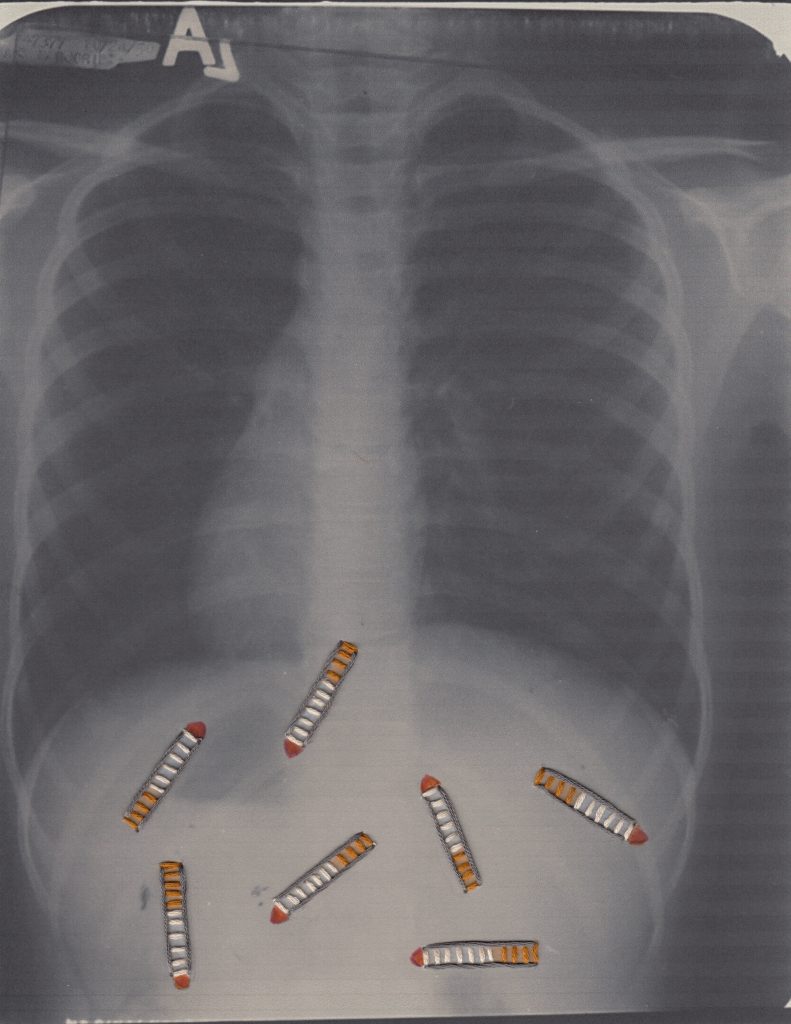

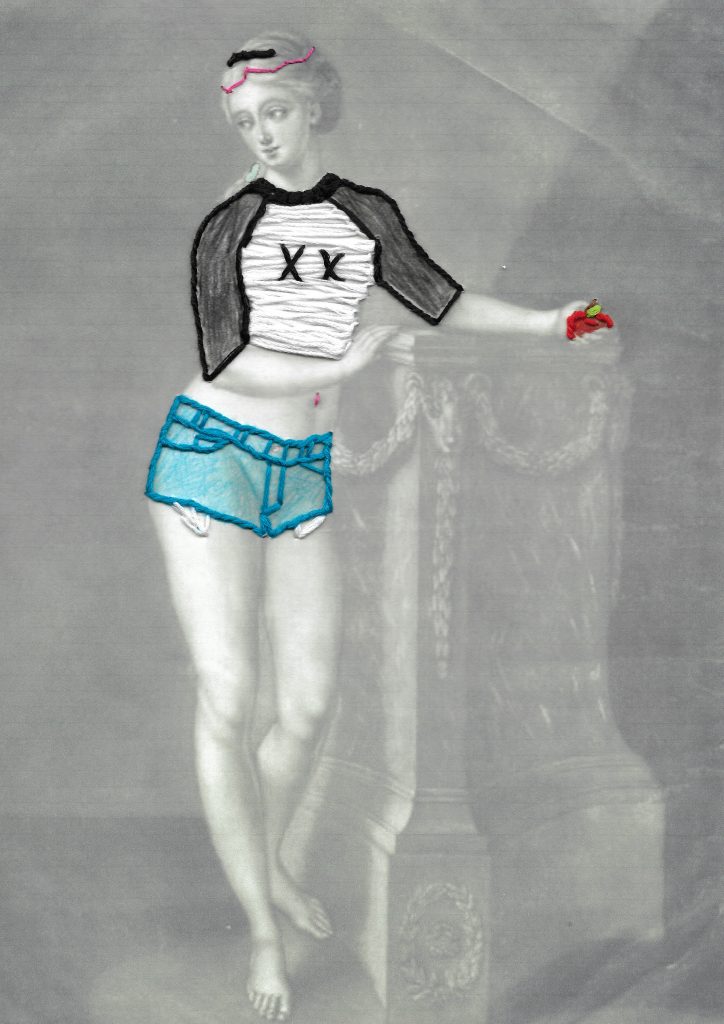

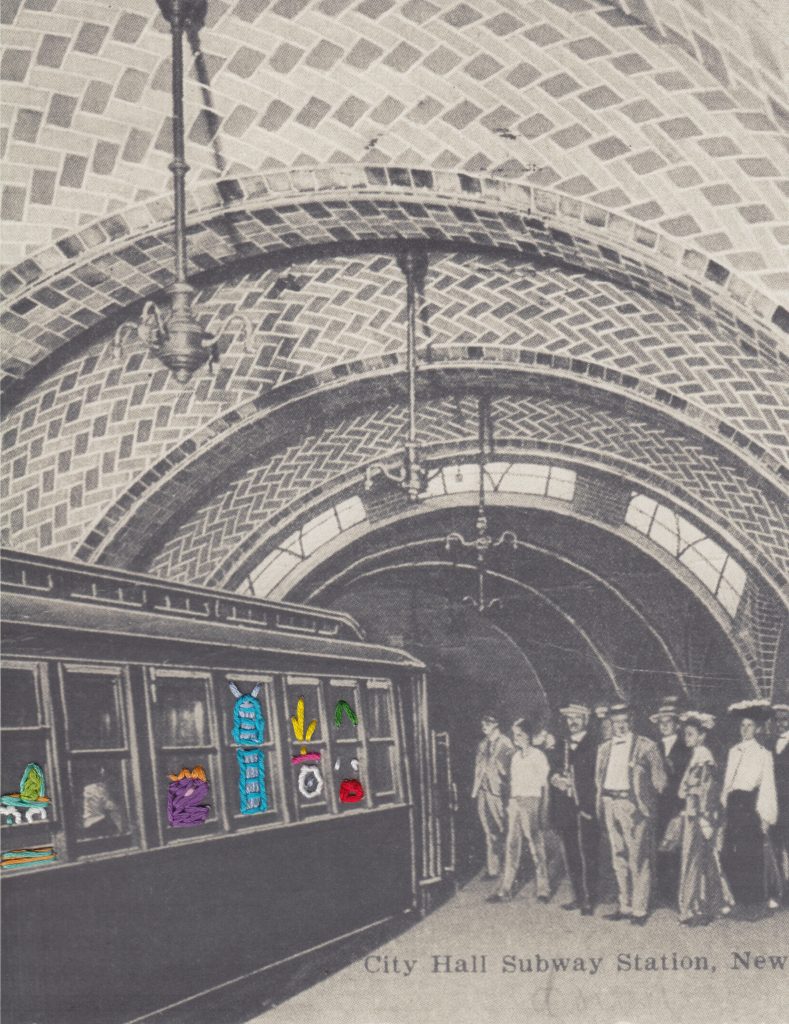

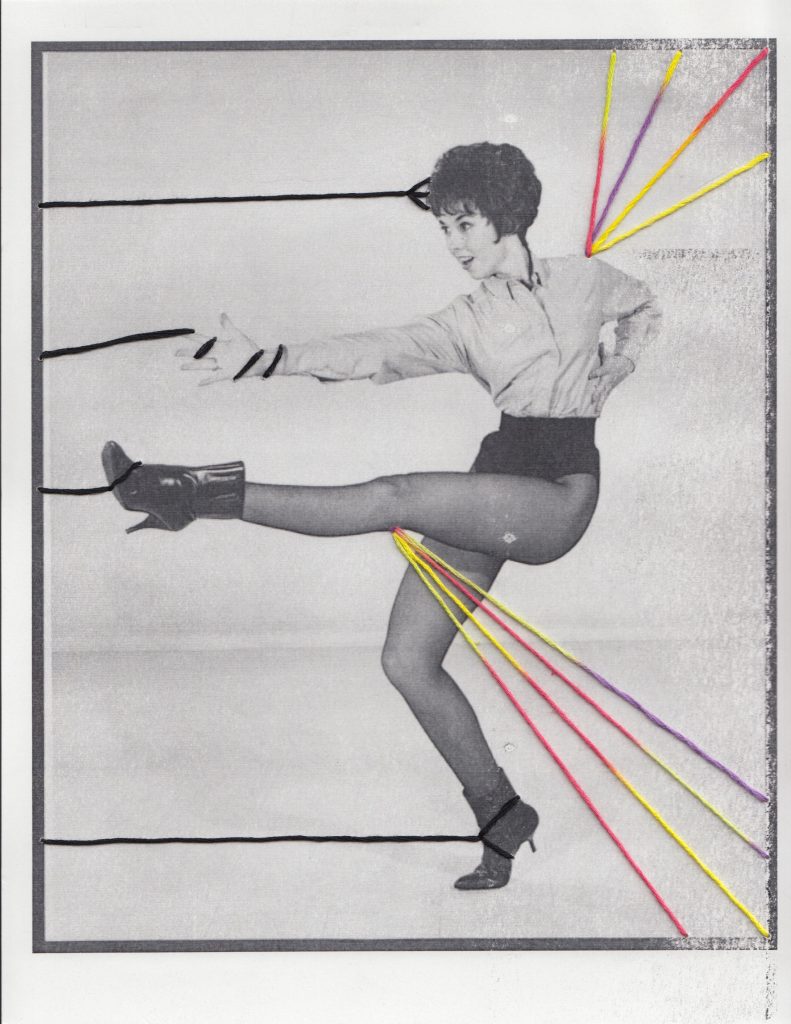

The Show Your Work series considers the human tendency to impose our own narratives on another’s truth, as well as the layered and complicated process of rewriting the present by reconsidering the past. Each image in the Show Your Work series is a previously discarded photograph dug up at an antique store or on a found-photo resale site.

To determine what to embroider on each image, I Google-searched a question sparked by the original photograph, selected the most intriguing image that showed up in the Google results, and then embroidered that web-found image onto the original photograph.

The framing methodology of double-sided glass frames encourages viewers to turn the frame around to see the back of each altered photograph—to see the work. The flip side of the photo can reveal the history of the photo, a pentimento of its years as a multi-purpose object, and hint at the many hands that have touched it. See the messy embroidery backside not often shown by artists and crafters, find the Googled question in my handwriting, and read any prior markings by previous owners of the photograph (including years, names, notes, and/or antique store sales information).

In a time that’s all about content generation, what do we do with the “content” that’s already here? This work also engages contemporary culture’s historically profound ability to divine answers almost immediately, as well as the tension and confusion that results from our very mortal inability to find the answers we are most often in search of.

This presumptuous layering work was partly inspired by photographer Cindy Sherman’s famous 1981 photograph “Untitled #93,” which, though technically not titled, she calls “The Black Sheets.” Sherman is purposefully ambiguous, leaving the viewer to make their own assumptions about the image—often vastly different from her own intent when staging the portrait. She says, “I think of that character as having just woken up from a night out on the town and she’s just gone to bed like five minutes before and the sun is waking her up and she’s got the worst hangover and she’s about to pull the sheets over her head or something and go to sleep. And other people look at that [photograph] and think she’s a rape victim.” Why do we see what we see? How does our perspective get it wrong? What does it get it right? Is there a space in between these extremes and, if so, how do we hold that space for ourselves and others?

Gone, Country

2017–2018

See all my work from this series on Instagram @jackiemanteydotcom

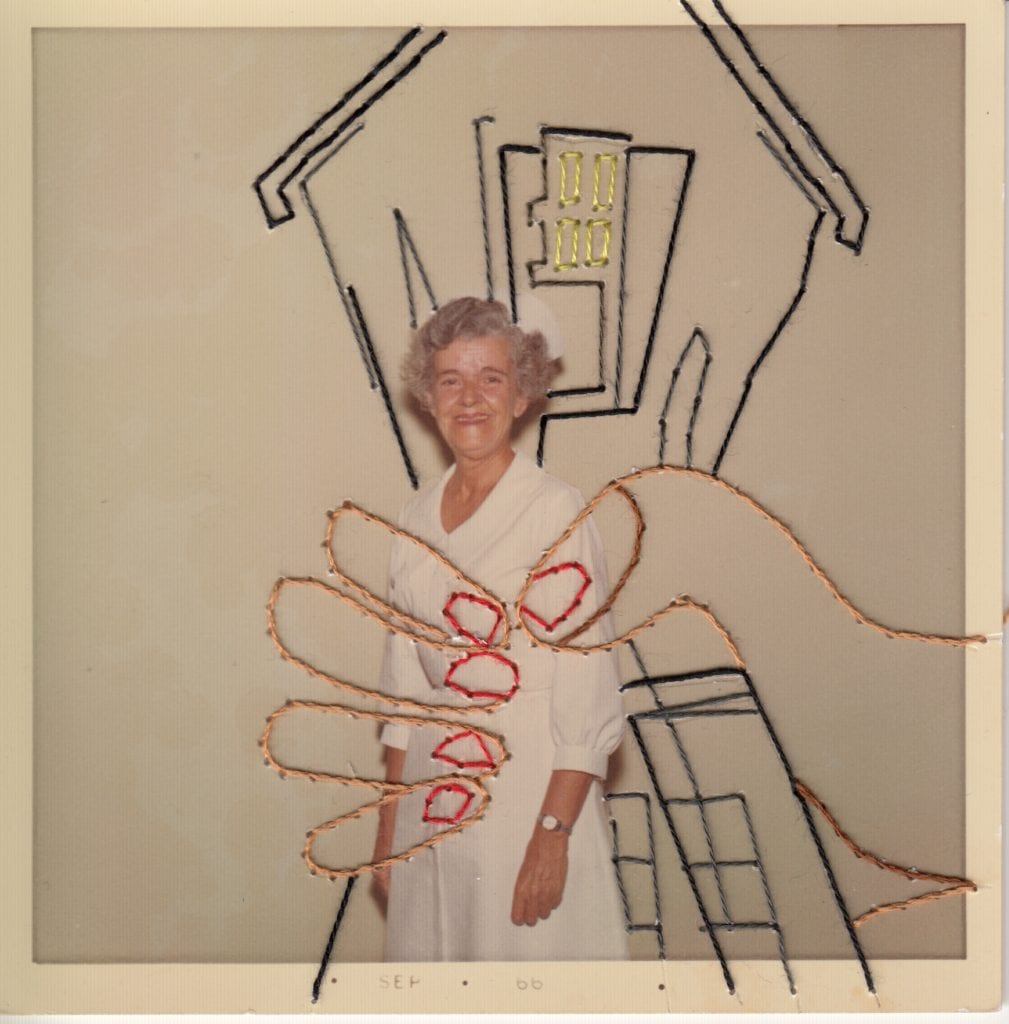

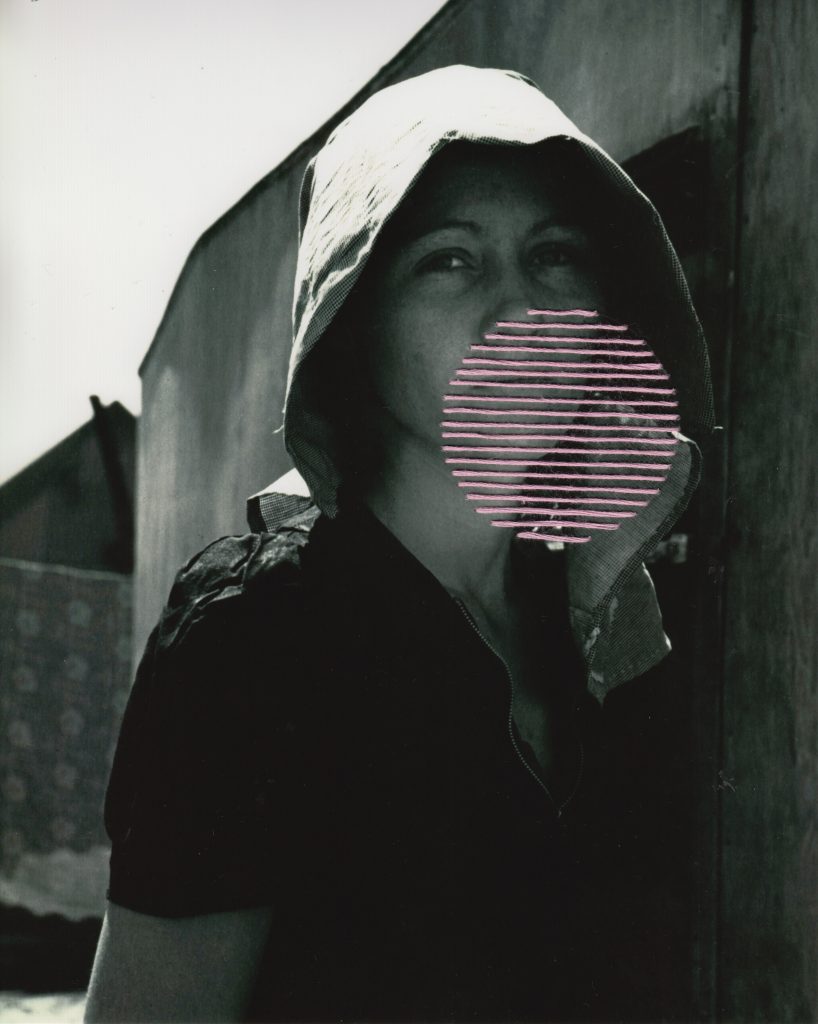

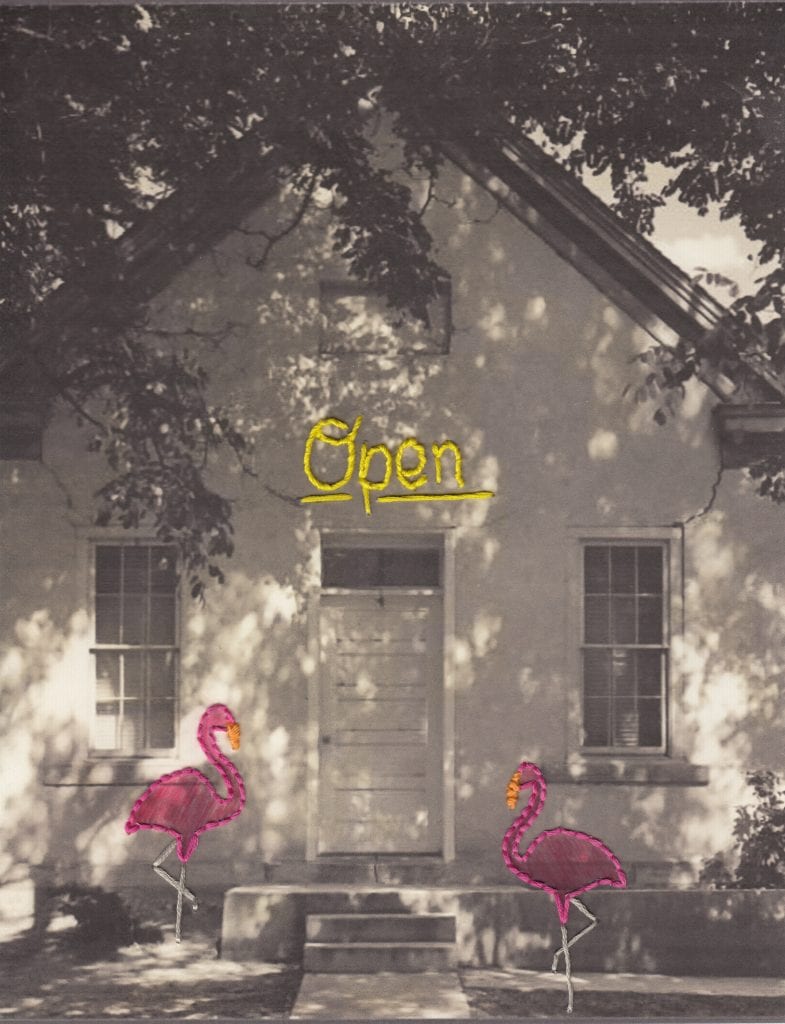

The black and white images in Gone, Country were selected from the public domain of the New York Public Library Digital Collection. The photographs used as source material for the exhibition were search results for the words “Home,” “Ohio,” “Chicago,” “Local,” or “Native.”

The work explores America’s contemporary rural/urban divide, a division highlighted and exacerbated by the corrosive 2016 presidential election. My embroidery on top of these historical images creates visual cues that warp the story of the original image. The resulting work is at once playful and unsettling, witnessed through the plastic lens of modern America, as well as our individual experiences of isolation as we struggle culturally with an identity crisis. As progress continues to polarize traditionally privileged communities, a look back at American history tells a more nuanced story.

Presented alongside each image title in Gone, Country is the original name of the historical photograph. The language and terminology used in these original titles is important. Whose portraits have names deemed worthy enough to record? What locations and homes have been recorded for posterity? How did Americans think of and name other Americans? What was recorded and what wasn’t? What visuals are provided, by fate and algorithms, as answers to a search?

I lean into these questions when rewriting each image’s story with needle and thread. Throughout the exhibition are evocations of both rural and city life; their traditions, aesthetic, and people; their similarities and power-sanctioned differences; and the things our country has taken, given, or brutally left behind. Each image is framed in repurposed barn wood that was torn down as America’s landscape changes. At its core, Gone, Country is a search for a place to land and effort to bridge an identity inspired by seemingly opposed forces.

Mildly Depressed

2016–Present

See all my work from this series on Instagram @jackiemanteydotcom

In spring 2016, I moved to Chicago and, at the same time, quit drinking. These were two ~huge~ life changes, and I found I had a lot of time on my white-knuckled hands, in a new place where I knew, like, three people.

Writing (my main squeeze at the time) during early sobriety was too challenging. I couldn’t put into words what was happening to me in recovery. I needed something visual and physical and slow-going and mind-numbing. I began making embroidery art on found imagery that spring. The work was a salve. A meditation. An outlet. A distraction. A time suck. An architecture for a different lifestyle. I was essentially punching one hole in the darkness at a time.

I called the work at that time Mildly Depressed, because that was the best way I could describe how I felt and why I was doing what I was doing. Years later, still sober (and way less sad :)), this work continues to be a calming and introspective space for me. Many people champion alcoholism or self-destruction as an integral cause and effect of creativity, but I have found the opposite to be true. Sobriety led me to a profound well of creativity that was waiting to be discovered deep inside myself. I’m still surprised I had/have this inside of me. (Who knew?!) I think of my evolving visual art practice as a gift of sobriety—a gift I am endlessly thankful for.