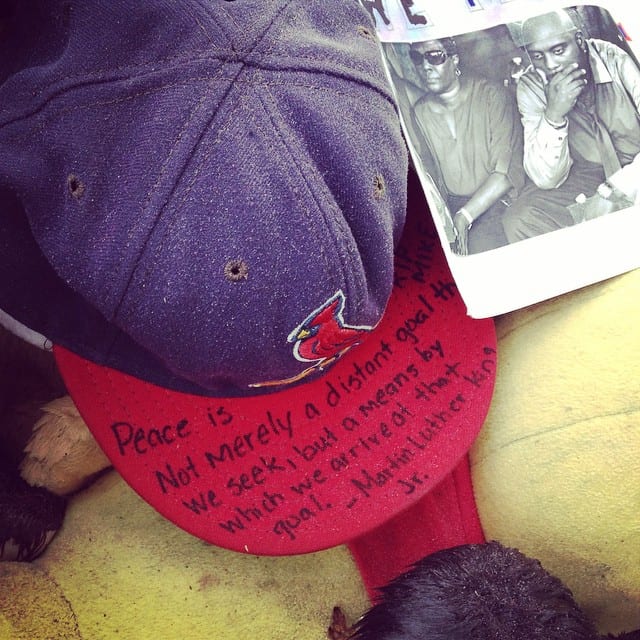

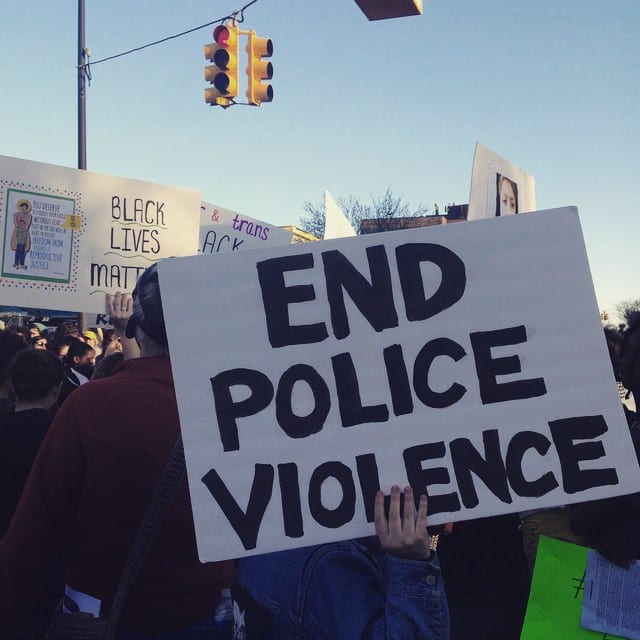

All photos courtesy Austin McCoy

I’m lucky enough to have a handful of academics as friends in my Facebook feed. As the post-election noise gets ever more urgent and confusing, I’ve turned to these friends for article links, books to read as I scramble to get a more careful background on some of these issues, or calm, reasoned takes on what is happening now and what we can do in the future.

With the scourge of fake news stories and the normalization of prejudice-through-language happening in non-fake news sources, I’m overwhelmed. I guess I’m craving to see where we are through the lens of education and history, because those are where I’m convinced the path to truth and answers can be found.

Apropos, then, that I turn to Austin McCoy, a very well-educated historian.

I originally messaged him to talk about the Black Lives Matter movement. I focused my questions on how white people like me, and most of you readers, can be participants and how can we educate ourselves to be better advocates for equality.

I think the most obvious thing we can do is listen to minority experiences and then, with compassionate self-criticism, ask how we, especially white liberals, act out our own systemic bias. Because we do. I do, too.

The racism, straight-up not stirred, hurled at Austin on Twitter recently has been outrageous. I’m always in awe at how gracefully Austin handles the hatred, amazed at his ability to peel the leeches off and stay standing, fighting for what he believes in in a way that is underpinned by the calm, compassion and consideration he encourages his opponents to employ. That resilient courage is inspiring, which is probably why he’s become a strong voice in the organizing he leads.

He’s a role model for me and many.

Today, Austin brings that thoughtful, powerful presence here. Following are Austin’s thoughts on post-election America as well educating ourselves on the African American experience, which seems particularly poignant after this weekend’s big news stories about racial disparity in the New York parole system, the jury in the Walter Scott shooting and the alarming story of Joe McKnight’s murder.

As for me, I’ll be heading to the library after work today to pick up one of his book recommendations. And I look forward to soon buying his own book.

Tell us about your background and the work you do now.

I study 20th Century U.S. history, particularly African American history, social movements, and labor and political economy. Currently, I am working on a book project that examines the progressive left in the Midwest and their movements around the 1960s uprisings, police brutality, the war in Southeast Asia, and economic justice. I serve as a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Michigan.

My background inspired my research. I grew up in Mansfield, Ohio, which is a small deindustrialized city. Initially, I was interested in how progressives responded to factory shutdowns because so many closed in Mansfield. The Mansfield area lost twelve manufacturing plants, including the Mansfield-Ontario General Motors factory, since 1971. I am a son of the black working class. My grandfather, father, mother, uncle, and aunt worked in factories in Mansfield. I was also an activist looking for guidance in how to organize for racial and economic justice.

I did some organizing work as an undergraduate student at The Ohio State University, Mansfield. I focused mainly on issues of race and diversity. I was one of a very few African American students on campus. I barely saw any other black students on campus and was typically the only one in my classes. Some of us also organized and started a little leftist magazine—we called it Spirit of the Nation. Since I have been at the University of Michigan, I have organized around issues of racial justice on campus, police killings (“Black Lives Matter”), and now against white supremacists, or whom some in the media have called the “alt-right.” I helped organize an all-night teach-in to support black undergraduate students at Michigan seeking racial justice. I also participated in Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Cleveland, and Chicago.

When and how did your family first talk to you about race?

I cannot recall the first time my parents first spoke to me about race. I remember my mom would talk to me about always having to be careful because black men were becoming an “endangered species.” This was probably during the late-1980s or early-1990s. I was really young, maybe around ten- or eleven-years-old. My mother worried about me because she believed that I would be a target, or a fall guy, if I got into a bad situation while hanging around white and non-black folks. She talked to me more about how to interact with police and other authority figures as I entered my teenage years. This “endangered species” discourse circulated among other black folks too. I always tell people that one of the primary examples of this is in hip hop. Ice Cube and Chuck D recorded a song together that appeared on Cube’s first album, Amerikkka’s Most Wanted, called “Endangered Species.” This was a gendered phenomenon, obviously. My parents were protective of my sister, but mom never spoke as if she was in imminent danger.

What makes you proud to be a black man?

First, I’m proud because of my family—my parents, my sister, my brothers, my grandparents—especially the struggles we have endured. Second, I’m proud of our extremely complex history. It seems cliché, but since I went to college and started studying history, I became more inspired. Black folks destabilized the slave system and overturned Jim Crow in the South and simultaneously challenged racism in the North and West. Hip hop culture also instilled a pride in my racial identity. I would name some specific artists, but there are too many to name. Nas, Public Enemy, X-Clan, Dead Prez, Ice Cube, Talib Kweli, Lauryn Hill, A Tribe Called Quest, and the Wu-Tang Clan are at the top of my list, though. Obviously, black history and hip hop culture are also crooked vessels. They are not perfect and can perpetuate problematic views of gender and sexuality. But, my point is that I had to learn how to hold what inspired me in tension with those problems.

What inspires you to do the work you do and face the hate you do on a daily basis?

Sometimes I do not know what motivates me besides the obvious—a desire to address and eradicate various forms of oppression and inequalities. I have been doing some sort of organizing work for a long time, so I often pull water from that well, and it runs deep. What keeps me going is knowing that the causes I believe in are just. But I also know that I do not have the luxury to be a bystander, especially now. In the last couple months, I have encountered racism more on social media since I have a presence. What also drives me now is the desire to help people organize themselves to change the world around them. I want to help anyone who wants to organize to be, well, better organizers than I. Watching folks develop the capacity to organize and resist is also inspirational.

How did these election results make you feel?

I felt terrible. I felt on-edge and on the verge of crying. I also felt physically sick. The thing that some Trump supporters clearly did not understand was that some of our feelings about the outcome of the contest actually transcended the election, itself. Many of us were, and are, not sad because a Republican won. Many of us are fearful because we have taken Trump at his word—about Muslims, undocumented folks, women, and Black Lives Matter.

Beyond the racist rhetoric and actions Trump has emboldened, are there any policies or actions the Trump campaign has promised that should have us on high alert?

The real question is where to start—the proposed Muslim registry, mass deportation, Trump’s demonization of Black Lives Matter and support for a national “stop and frisk” law (which would not be constitutional)? As I write this, social media and news outlets are reeling at Trump’s latest tweet suggesting that those who burn the American flag should lose their citizenship and/or be jailed. White nationalists and white supremacists see Trump as an inspiration and an opportunity to mainstream their ideas and influence policy. Trump’s rhetoric has emboldened many of these folks to harass people like myself on Twitter and social media, and, even more disturbingly, to commit hate crimes. Donald Trump and white nationalists are a threat to what little democracy we may have. What is good is that we are not sure what he will actually do, but we are wise to take him at his word, or tweet.

How is All Lives Matter counter-productive? What you say to people who come at you with that?

The counter-slogan, “All Lives Matter,” misses the point and is really a distraction from the problem that many people of color, particularly black people, face—disproportionate state violence. All African Americans, trans people of color, and Native Americans are more likely to be killed by police. Residential segregation, the poverty concentrated in these spaces, mass incarceration, and an unwillingness for Democrats and Republicans to devise policies that could address inequalities show a disregard for black bodies. Black folks, as well as many poor people, have become more disposable as inequalities have widened. So, the easy answer is there is no need for a black lives matter movement if all lives truly mattered. If all lives mattered, then there would never be a time when the state would circumscribe black folks’ civil liberties. We wouldn’t be criminalized by laws. We wouldn’t be racially profiled. We would not have to contend with negative racial stereotypes that suggests we are criminal, either due to biology, behavior, or geography. Our families would not have to contend with the negative racial stereotypes when loved ones are killed by the police. We would not be blamed for our own criminalization nor our own deaths.

What can white people who want to be agents of change do to help, especially in this oncoming environment of a Trump presidency?

First, white folks need to support the Movement for Black Lives’s platform. This needs to be a point of conversation among white folks. White and non-black folks should consider supporting and organizing around a political platform that doesn’t totally center on their own preferences, or what they consider a “universal” political vision. Then, as white folks voice their support for the Movement for Black Lives’s platform, they can continue to find ways to educate themselves about the history of structural racism, patriarchy, settler colonialism, Islamophobia, economic exploitation, and xenophobia. All of these phenomena are connected. These are the phenomena that obstruct unity, democracy, liberty, and equality. White folks, as well as all of us, have to think of the ways in which we are complicit individually and collectively.

Do you have any book or reading or even movie/ documentary recommendations for people who want to learn more about racial injustice? Where are good starting points for people who might not be educated on the complex history of racial injustice in America?

This is a tough question for an historian because there are so many!

Martin Luther King, Jr’s Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? has been formative in my understanding the challenge of attaining racial justice after the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts. In this text, Dr. King is extremely critical of white liberals and those who thought the movement had realized racial equality. He also offers his thoughts on the Poor People’s Movement and the prospects for democratic socialism in the U.S.

Toni Cade Bambara’s The Black Woman: An Anthology is one of the first collections about intersectionality edited by a black woman. This text, published in 1970, provided necessary critiques of white liberal feminism, black power, and racist and sexist views of the black family and black womanhood. One cannot understand the history of the women’s liberation movement and black feminism without consulting this collection.

Keeanga-Yahmatta Taylor’s From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation and Jordan Camp’s and Christina Heatherton’s Policing the Planet: Why the Policing Crisis Led to Black Lives Matter are great resources for understanding the historical context of the Black Lives Matter movement. Taylor offers a concise radical interpretation of race, racism, black politics, and policing after the 1960s. Camp’s and Heatherton’s book is a collection of essays and interviews by intellectuals and activists. It examines the issue of policing and state violence from various points of view. I am teaching a class on resisting state violence next semester and I plan on assigning all of parts of both texts.

I would also suggest Robin Kelley’s Black Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination, Barbara Ransby’s Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement, and Michael Dawson’s Blacks In and Out of the Left because they provide the hope we need.

Movies and Documentaries: I love HBO’s Boycott because it offers a great insider account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution resonates with our contemporary moment.

Can you offer any words of wisdom or hope to people and especially minorities who feel threatened by this new president?

There is not anything I can tell minorities, or folks marginalized in our society, something they do not already know. I think Trump supporters should try harder to understand why marginalized folks feel threatened. I am confident that the real defenders of democracy—justice-seeking students, community organizers, intellectuals, teachers, journalists, cultural critics, comedians, artists, and librarians—will challenge this new regime and make the president-elect feel uncomfortable with pursuing his program each day he is in office. My hope continues to lay in all of my friends, accomplices, and the folks that I don’t know, and their willingness to organize at the drop of a dime and put their bodies on the line. I do not have any words because there is no hope without us working and struggling together.

If you could invite three people to a dinner party, living or dead, who would they be and why?

Three people? Wow. I am going to name five — Frederick Douglass, community organizer Ella Baker, author Toni Cade Bambara, historian Howard Zinn, and Martin Luther King. I would want to talk to all of them about how we can resist the new administration. I work best with a large team.