Bust magazine readers may recognize the name Mimi Matthews.

This California-based writer pens a weekly column for the feminist magazine’s website. It chronicles the mostly fascinating, truly fabulous, and sometimes straight-up weird life and style aspects of Victorian culture.

Matthews does rabidly precise research and has a thoughtful eye for a good story — from Victorians’ beautiful fall dresses made of a toasted-orange fabric (the Pumpkin Spice Girls?) to the fate of old men who married young women in the 1800s (it’s, as predicted, pretty yikes) to their gone-viral beauty obsessions (mmmm, violet perfume).

You can (and should) read her Bust entries here. I, being an auburn-leaning ginger, am partial to the one about why auburn haired women were beloved (we cray!):

Auburn hair, with a florid countenance, indicates the highest order of sentiment and intensity of feeling, along with corresponding purity of character, combined with the highest capacities for enjoyment and suffering.

Matthews has two non-fiction books on the way, including “The Pug Who Bit Napoleon: Animal Tales of the 18th and 19th Centuries,” due out in November, and “A Victorian Lady’s Guide to Fashion and Beauty,” due out July 2018.

As an attorney with a Juris Doctor and a Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, it’s no surprise Matthews can expertly handle not only separating fact from fiction — but making them play together nicely.

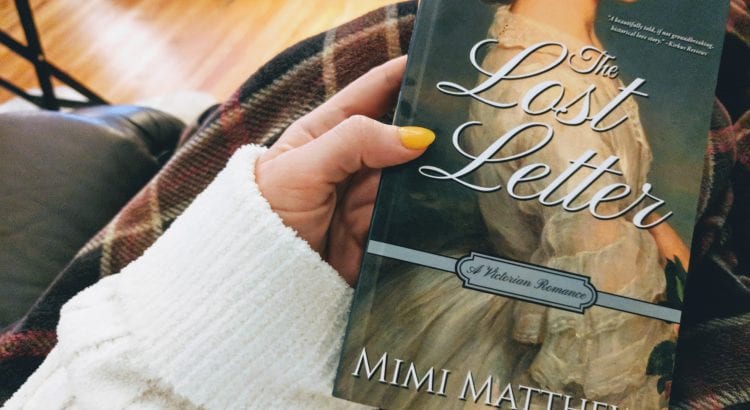

Proof: Her debut fiction novel “The Lost Letter.”

This Victorian romance is the perfect companion for a cuddled-up Fall Saturday. It follows the story of the dynamic Sylvia Stafford. The tragic death of her father demotes her to a life of spinsterhood (no more pumpkin colored evening gowns for Ms. Sylvia!), until fate intervenes and she is reunited with her former love, the once charming Colonel Sebastian Conrad, gone surly and sour from a devastating battle wound. The Victorian countryside is the lush backdrop for this story of love, loss and redemption.

In the following interview, Matthews talks about her own love affair with the Victorian era, how she balances research with crafting fiction, what she’s working on next, and advice she has for anyone writing a historical novel.

Oh, and which Bronte she would invite to a dinner party. Would you be able to choose just one?

***

What do you love about the Victorian era? What draws you to it?

The Victorian era has always appealed to me on multiple levels. First, there’s the obvious: the gorgeous fashions—from wire crinolines to enormous bustles. Then there’s the emphasis on manners and decorum; the strict societal rules for ladies and gentlemen and the limitations imposed on courting couples. The Victorian era was also a time of enormous advancements in industry, medicine, and the rights of women. Aniline dyes were discovered, the sewing machine was invented, train travel became ubiquitous, and women shed their cumbersome skirts and hopped on safety bicycles, an invention which gave them enormous independence. What’s not to love?

What made you want to write fiction about a subject whose real-life stories you’re so knowledgeable about?

The Victorian era has a wealth of fabulous history to tap into. And I already write so much about it in the non-fiction realm, it seemed only natural to set my novels there as well. I think my readers would have been disappointed if I hadn’t. Not to mention, when I read historical romances, I really notice when an author gets their history wrong. I was determined that I would use my knowledge of Victorian social history to help me get my own novel right.

How do you balance being true to the gender roles of the Victorian era with creating an interesting woman and romance your reader wants to root for? (Hello, Sylvia!)

It’s a challenge, especially as I hate when characters in a historical [novel] come across as nothing more than modern men and women in costume. This is why I really liked writing Sylvia. Since she had essentially been ejected from fashionable society, she wasn’t strictly bound by Victorian social conventions. It was up to her to make her own way in the world. It was a grim situation, but one that allowed her to gain a measure of feminine independence. At the same time, she was still quite constrained in regard to how she could interact with the opposite sex—especially Sebastian. Also, it helps that a lot of the emotion that she and Sebastian felt—the romantic angst, fear of rejection, and feelings of betrayal—is emotion that many of us have felt at some point in our modern romantic lives. This made the characters relatable in spite of the restrictions imposed by the era.

How did your background studying Victorian era history and culture help and/or hinder the fiction writing process?

It helped tremendously in that I was able to draw on my knowledge of Victorian fashion, etiquette, and social norms without having to do too much additional research. It hindered me on occasion because I’m such a stickler for historical accuracy and, in writing a scene, I would often think, “They would never have said/done this!” It was sometimes hard for me to put that aside in order to allow my characters to have time on their own to talk—or to kiss!

Do you have any advice for writers about doing research for a fiction novel?

If they’re striving for true historical accuracy, I would strongly advise them not to limit their research to uncited blog posts or Wikipedia articles. They should read historic newspapers, magazines, and books. They should get a feel for the language and the behaviour of the era in which they’ve set their story. And if they’re writing about something they know nothing about—like horseback riding—they really need to have their research down. Nothing is more irritating to a reader than being absorbed in a story only to have some anachronism wrench them out of it.

What do you listen to or watch or read to get pumped up to write?

I get most pumped up to write when I’ve been researching something. I often find some odd Victorian fact which inspires me to envision a scene or a scrap of dialogue. Victorian fiction—especially classic novels like those by the Brontë sisters, Margaret Gaskell, or George Eliot—also inspires me and helps to get me in a certain frame of mind. As for music, though I love it, I can’t really listen to it when I’m writing. It’s too distracting. I have to have everything super quiet.

Do you have a daily writing routine or schedule when you’re working on a novel? If so, what is it and how does this help you get the work done?

I had to finish my latest non-fiction book, “A Victorian Lady’s Guide to Fashion and Beauty,” on a hard deadline. I was at my computer writing every day by one o’clock. I would then write straight through until dinner. For fiction I’m not so strict with myself. I write whenever the muse takes me. There are some days I can write thousands of words. Other days I only write a few hundred—or none. I aspire to be more disciplined (and more prolific), but life often gets in the way.

Do you want to write another romance set in this time period? If so, what will you do differently or how do you want to grow or explore as a writer in a second book?

I’ve got a few other novels set in the Victorian era that will be out over the next year or two. “The Viscount and the Vicar’s Daughter” is coming in January. I actually wrote it before I wrote “The Lost Letter.” Because of that, I’m not sure how much it will read as if I’ve grown as an author. It’s far less angst-ridden than “The Lost Letter” was. In fact, it reads more like a romp, with an impulsive, rakish hero and a prim heroine who can’t resist him. Following that, I have a much darker Victorian novel coming out (as yet untitled). It’s about an injured soldier in coastal Devon who places a matrimonial advertisement in a London newspaper. The woman who arrives on his doorstep is not quite what he was expecting. This novel allowed me to explore more sinister themes, including those relating to the legal power that Victorian men had over their wives and female relations.

What has been inspiring you lately?

I’ve recently been researching 19th century breach of promises cases. In many, the gentleman had written compromising letters to his betrothed before breaking their engagement. The jilted girl’s father then used the letters as evidence when bringing suit. I’m planning on using one of these old cases as a basis for a novella about a broken engagement which results in a breach of promise suit. I’ve already written the first five pages. We’ll see where they lead!

If you could invite three people, living or dead, to a dinner party, who would they be and why?

I’d like to say Queen Victoria would be on the list, but I actually think she’d put a damper on dinner conversation. The guests would be too intimidated to speak. Instead, I’d invite all three Brontë sisters, Charlotte, Emily, and Anne. They were three of the most talented authors of the Victorian era. I would love to hear their thoughts on life, love, and the business of writing.