Dawoud Bey is a MacAurthur Genius Award-winning portrait artist whose most moving photographs are black and white images in urban settings; however, his exhibition currently on view at the Art Institute of Chicago happens across a different landscape.

Titled, in a nod to Langston Hughes, “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” is a compilation of 25 photographs taken of places in Hudson and Cleveland, Ohio, that marked the end of the Underground Railroad.

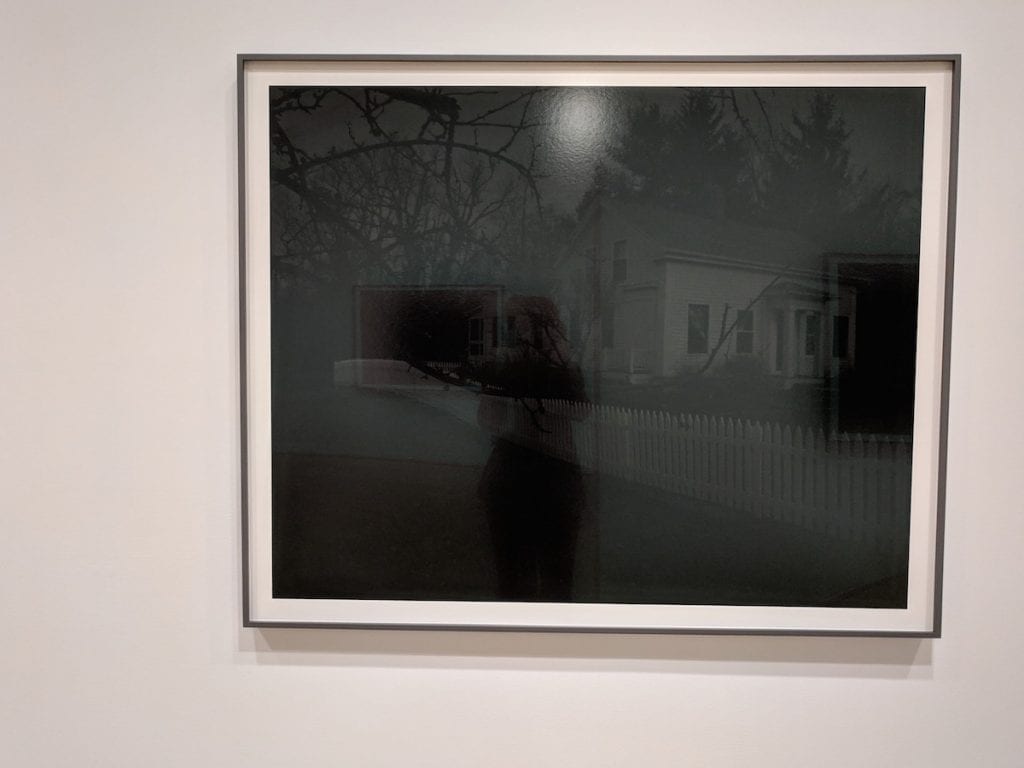

The large-scale images are darkened to mimic the blackness of night, a time of day when it was “safest” to run. The darkness makes it hard to see what you’re looking at, inducing a sinister terror that must, when you think about it, only be .01% (if that) of the sinister terror runaway slaves felt when approaching these final stops toward freedom—a term that feels especially meaningless when faced with the final resting stop, Lake Erie and sky. Canada’s freedom on the horizon, but at what cost? How did these people ever feel free or safe or whole? It seems as impossible as swimming in the dangerous choppy waves of the photograph.

Their reflective nature is particularly Bey-brilliant. With this effect, the viewer sees themselves in the image, in this situation, both long ago and in the modern world. At first, I thought about how alone these images made me feel, no human to be found, just the potential for danger that had to freeze you in your tracks. Seeing a shadow of myself in each image, I also thought about the ways white supremacy has shaped my own understanding of the world. How its effects linger today. I thought of Flint. Of Chicago police brutality. Of my own willful blindness that contributes to modern racism.

I was moved by the titles of his images, too. A forest. A marsh. These seem idyllic to me—because they can. But in light of the darkness of these settings and the truth behind them, I understand how these words and places represented a challenge, a cover, an enemy to the people who had to escape through them without the cover of peace… or even hope… or even, sometimes, other people.

Outside the gallery is a wall of framed photographs Bey curated from the AIC’s private collection. In addition to harrowing images of the murder that racism has justified on American soil are images of people who fought back and found strength in the darkness. Their courage is breathtaking.

The landscape portraiture Bey picked to include in the roundup is also meaningful. A particular Ansel Adams image of a tree, which, in a different context, I would have mused on romantically or in a rosy awe of nature, gave me chills instead. The photograph’s juxtaposition to a lynched murder victim evoked the trauma of a tree, how everything has been affected exploited in the name of “natural order.” It’s a devastating exhibit. It’s an important one. It’s on view through April 14.