Agnes Richter was institutionalized in Germany in 1893 when she was 49 years old. She pieced together this jacket during her time in the asylum using materials on-hand, like linens, wool, and thread, likely from her work as a seamstress in the institution. The embroidery is worn down and sweat stains abound, but some of the writing can still be read in deutsche schrift, a German script that’s nearly obsolete. Some of the phrases historians have deciphered: “I am not big,” “I plunge headlong into disaster,” and “583m,” her case number. Read more here.

Tag: art you should know

Three things that, much to my surprise, gave me goosebumps this week

Eminem’s verses on “Caterpillar”

I rely on Justin to keep me musically relevant and he played this song for me last night on our drive home from Denny’s (home of the 11:30 pm breakfast-skillet-sanity-saver). Eminem is a genius. His syncopation, cadence, rhyme, and god-like wit are on full display in this song. What a fucking writer.

Jen’s death scene on “Dawson’s Creek”

We finally finished the last season of “Dawson’s Creek” on Hulu following a binge of all the seasons. It was my first time watching any of it, but I knew (because I didn’t live under a rock in the early 2000s like I kind of do now) that Pacey gets the gal and Jen bites the dust.

That said, I think I would have cried at poor, lovely Jen’s death regardless, but goosebumps? That was courtesy how subtly, reverently they shot this. I love the choice to make the scene include only Jen and Grams in the room; a nod to the special relationship these two share and how, I think, Grams is really Jen’s soulmate, not Jack.

One final breath and a peaceful farewell while Grams is sleeping. It’s so soft, that goodbye from Jen. We don’t get to see her face full on through most of the scene, graciously giving us one last chance to see life from Jen’s perspective. And of course Grams knows immediately that Jen has died. Grams always knows. Grams carries Jennifer in her heart. “I’ll see you soon, child.” So gentle and loving a send off. So perfect for these two.

Bravo, 20 years later. Holds up.

The robot dress in “McQueen” the documentary

In an attempt to get as much out of our Movie Passes as possible before it goes popcorn-stuffed-belly up, we’ve been seeing a lot of movies lately, including “McQueen,” the visual feasty documentary about poor English boy turned fashion world icon Alexander McQueen.

1) Yes, go see it. 2) Justin and I both were a bit surprised when I reacted so physically to the robot dress scene from his 1999 runway show. I started CRYING and, of course, had the aforementioned goosebumps. It was surprising because there was no real lead-up to this footage; it wasn’t supposed to be this super emotional moment. But it was for me and I’ve been trying to figure out why.

Here’s what I’ve landed on: This robot spray paint dress finale happened in the midst of the Y2K scare, thus, everyone kind of saw these robots as menacing the model and destroying her virginal gown. But when I watched it, I thought it was so hopeful! The robots dance with the model, learn to move with her and try to learn her language, and then they add something to her experience. Sure, what they do to her dress is messy and has an underlying violence to it, but I see in this choice McQueen’s optimism, his openness, his ability to find something beautiful in the darkest places. Contrast that with his last runway show, “Plato’s Atlantis,” right before his suicide in 2010. The “robots” of that famous show were cameras that moved in front of the audience and in front of the models; watching, waiting, judging with a lens. In those robots, the violence was clear, the battle lines drawn, the hope gone. We should have known then the tragedy to come.

Art you should know: Watercolor tattoos by Amanda Wachob

Amanda Wachob is a New York-based tattoo artist whose method gets rid of the black border around a tattoo, opening the piece up for a softer, blended look with fluid lines that resemble watercolor paintings or gestural paint strokes. (Watch her and other pros talk about the watercolor tattoo movement here.)

If you want her to ink you next, good luck. Her waitlist is supposedly years long. Luckily, there are plenty of other ways for you to get your eyes on her work.

She prints hyper-close images of her skin tattoos on to silk canvases, and collaborates on super cool projects, such as the Skin Data project with neuroscientist Maxwell Bertolero. The pair recorded the time and voltage of her tattoo machine’s power supply as she created several tattoos, and they made images based on the data that resulted. I also really dig her collaboration with conceptual artist Mary Ellen Carroll, called HOLÉ. Participants wore an article of clothing with a hole in it and the artists then “filled the hole” with tattoo ink as if to say “all holes can be fixed permanently.”

In Amanda’s Bloodlines series, she tattoos a subject with meaningful shapes in a non-permanent water line. The body will eventually heal the tattoo and dissolve the mark into the skin, the energy of the symbol also absorbed symbolically into the person.

And while her specialty is skin, don’t miss her work on fruit. Tattoo artists practice on plant rinds before moving on to human skin. I’m particularly smitten by her lemon tattooed with the word “tryst.” What a great word, especially to betroth the bitter, beautiful, impermanent lemon.

Art you should know: Painter Toyin Ojih Odutola

Someone once asked Toyin Ojih Odutola, a contemporary portrait painter based in New York, what her purpose as an artist was.

This is how she answered: “To make the world less small.”

On the surface level, how she does that seems obvious. Toyin is Nigerian-born and grew up in Texas. The perspective her artwork brings to the white walls of traditionally white, male spaces is important as we grow the space for voices.

But diversity means more to Toyin than representation of skin color in art. Diversity also means diversity of thought in the room. I love this little reminder that “diversity” isn’t a call to lift up one voice over another; it should be an attempt to elevate all voices to an equal level so that we can hear, and ostensibly learn, from each one.

Making the world feel less small comes through in her art in very powerful ways. Not only does her portraiture capture and express the magic of black skin, the conceptual work of her images reveals much. For her recent exhibition at The Whitney, she presented life-size portraits from the “private estates” of two fictional Nigerian aristocratic families.

As i-D writes, these are “radically soft visions of black wealth” driven by Toyin’s diversification of the stories we tell ourselves.

“Toyin says this was the driving question for her Whitney exhibition: What if you claimed everywhere you go as a home? Some black people avoid traveling because they (reasonably) fear they’ll encounter racism. Toyin wanted to help ease this hesitation by depicting black people outside, in nature, swimming in lagoons, chilling on the beach, taking in the sunset.”

That sounds so simple… but when you consider all the ways popular media can misrepresent black experiences and bodies by the imagery they choose, Toyin’s portraits seem all that more powerful in their commonness of scene.

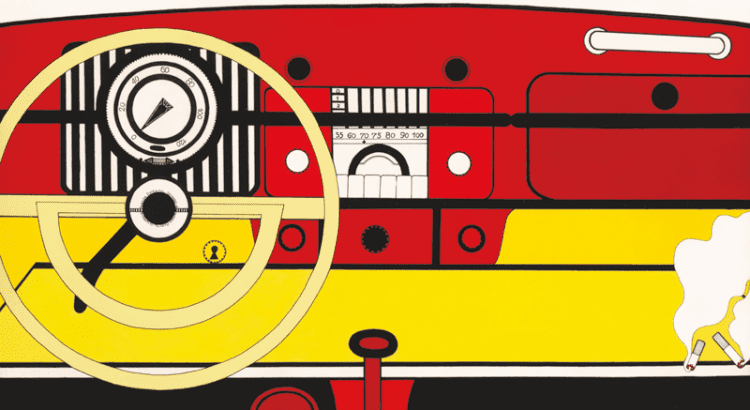

Art you should know: Involvement Series by Wanda Pimentel

Involvement Series by Wanda Pimentel, 1968-69, vinyl on canvas

Brazilian artist Wanda Pimentel began her series titled “Envolvimento” (or Involvement) in 1968, the year the country’s military dictatorship decreed one of 17 major institutional acts that gave the regime authoritarian rule and mostly threw judicial review in the can.

So, her dissent of the country’s politics and violence toward the powerless had to be somewhat veiled lest she and her work face censorship… or worse. At the same time, in other places across the world, pop art and nouveau realism were rubbing their graphically shaped stones together and making lots of boldly saturated sparks.

In the Involvement Series, Pimentel painted in vibrant colors but a reduced palette. Her flat scenes uncomfortably cram together interior objects, from which there seems to be no escape. Body parts hint at the humans in the rooms, but their disembodied, naked status comment on the feeling that humans can be props, just like the objects of consumerism they use and discard, use and discard.

“Everyday objects crowd compressed interiors and suggest acts of corresponding domestic labor. Figures are fragmented,” states the AIC placard. “In this canvas, two disembodied feet emerge below the red ironing board. Their owner is otherwise only indicated by the closet full of blouses and the ready iron, the trappings of consumer culture through which we assume and care for our external appearances.”

Trouble inside. Trouble out.

But there’s some exciting expression in the series too, again subliminally disguised. “Messy piles of clothing, pools of spilled liquid and slowly dripping faucets seem to reflect the recent collapse of the political order, but also the excitement of sexual self-discovery,” writes Frieze.

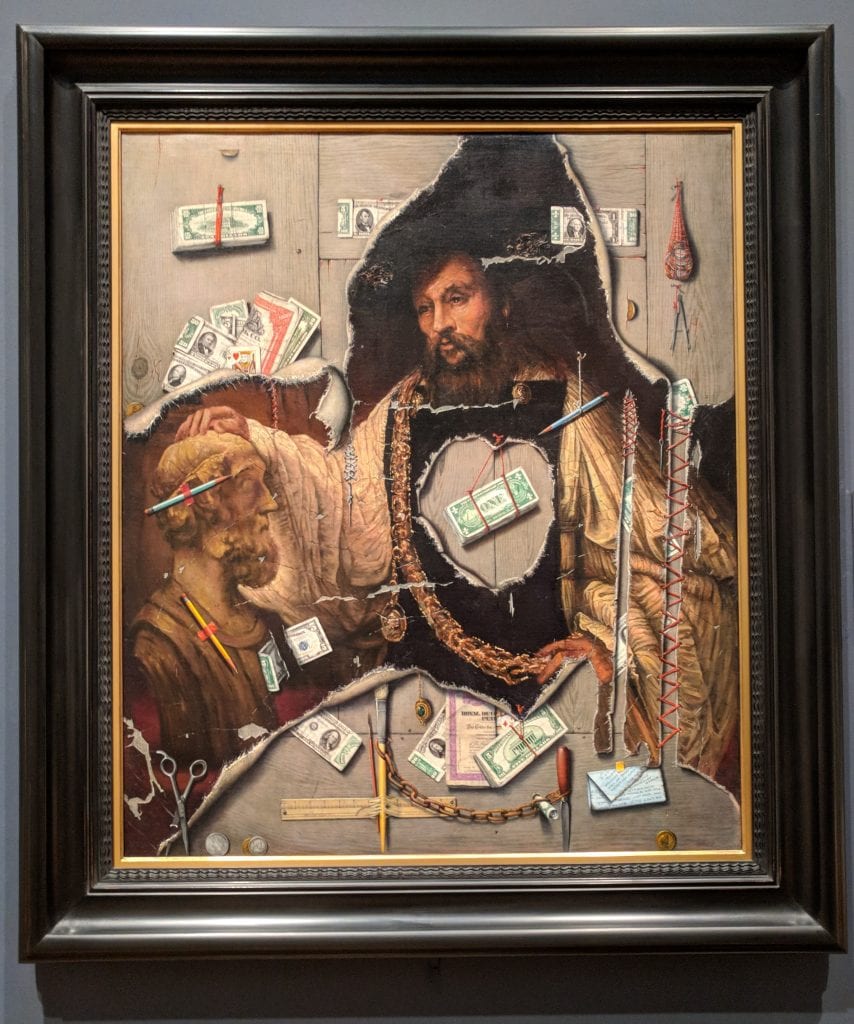

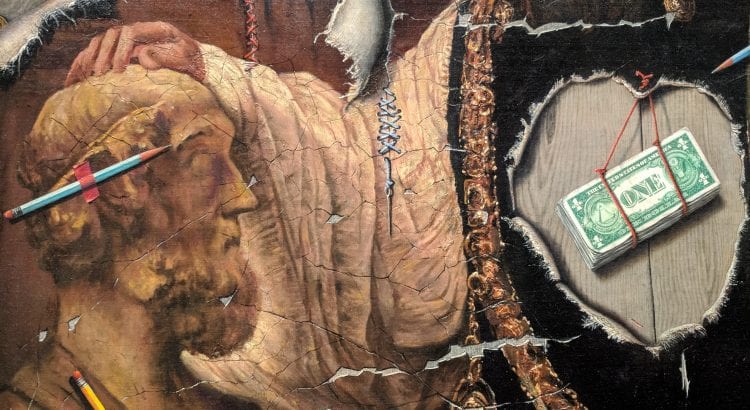

Art you should know: “Heart of the Matter” by Otis Kaye

So this guy, Otis Kaye, lost all his savings in the stock market crash of 1929. This loss had to have pissed him off or at least left him a little numb to and/or disillusioned by the financial world’s proclamations of glory, right? Right. He began making more and more forms of currency—coins, bills, etc.—the focus of his incredibly detailed paintings.

Decades later, in 1963, he created this oil on canvas masterpiece, “Heart of the Matter.” It “represents Rembrandt’s ‘Aristotle with a Bust of Home’ (1653)—which had been purchased two years earlier by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, for a record-breaking price—torn into pieces and surrounded by and even interlaced with money,” according to the Art Institute of Chicago’s placard by the painting. “At the very center appears a suspended stack of bills; the ‘heart of the matter’ is thus the close connection between art and commerce.”

Now, before you go judging the irony of an artwork with these anti-capitalist undertones now living in an art museum itself, consider this: It was given to the AIC as a gift by Anonymous.