The past few months I’ve been grooving to a morning routine that’s 100% helped me get 85% focused for each day. It involves some variation of tea (I’m that person now… tea drinkers are to blogging about being a tea drinker as marathon runners are to 26.2 bumper stickers), journaling, reading, and watching a meditation or an affirmation video. I know, affirmations seem so corny, but I swear to 20-something granola Jesus, they have helped me out of many a morning funk.

While I try to watch the meditation or affirmation videos ~mindfully~, I sometimes—almost all the time—end up getting distracted and, instead, mindlessly scroll through Pinterest (I figure my subconscious is picking up on whatever’s audibly streaming at me in the moment, so all is not lost). Pinterest is one of the few (two) social media platforms that don’t make my blood pressure rise (the other being Instagram). I end up pinning artwork the most. It’s such a visual platform and has helped me discover many artists whose work I really enjoy or feel inspired by. Or, the best, feel rapturously in awe of.

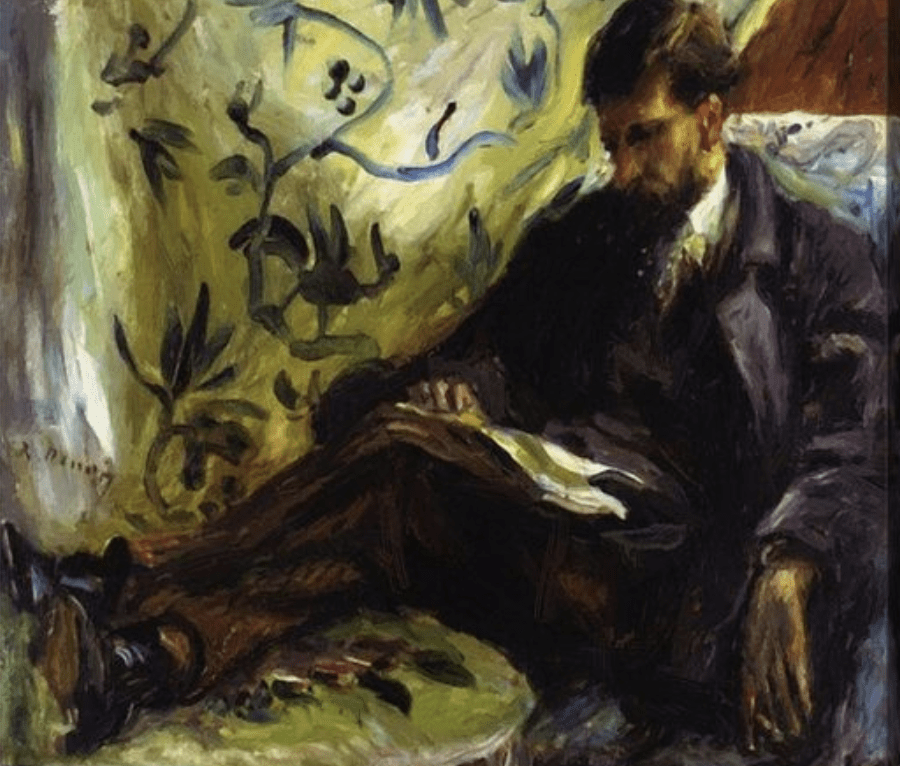

Genieve Figgis was one such morning scroll find.

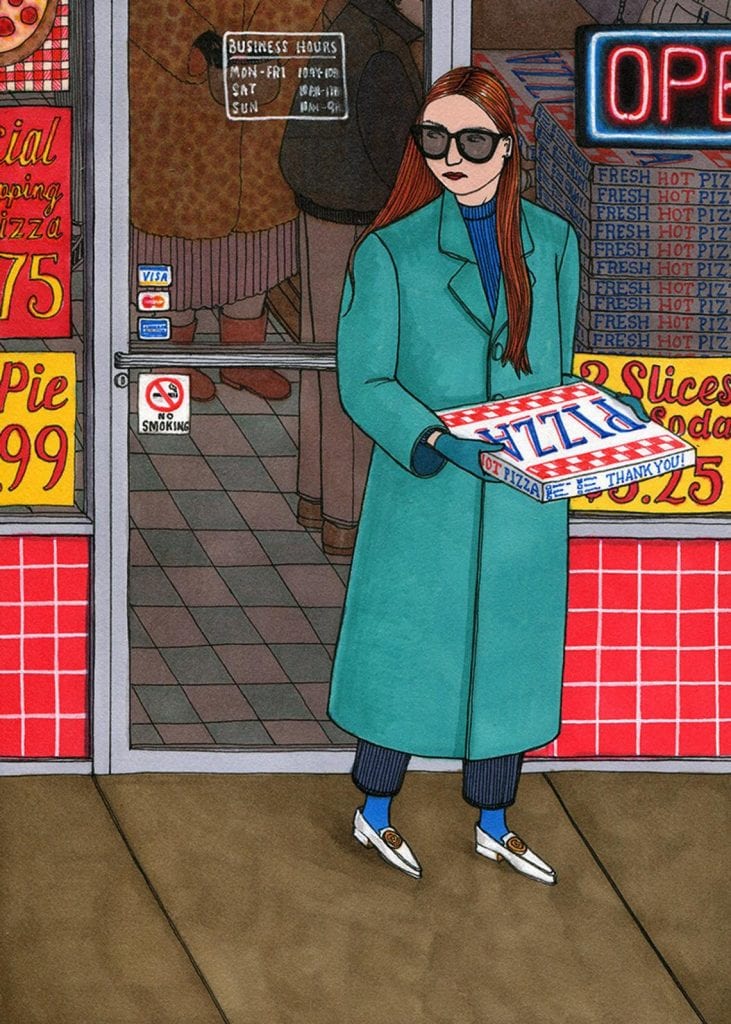

The Ireland-born and -based painter creates murky, dramatic scenes that are at once recognizable but elusive. They continuously capture my attention and then do something with said attention that’s increasingly impossible in an oversaturated visual culture—hold it.

“Not doing what was told would be my future, avoiding that, was just so fantastic”

Painter Genieve Figgis

Her work makes me feel like I’ve been in it before. Not just seen it; known it intimately. Like when you see, for a split second, a face on the street and you do a double-take because it kind of looks like a kid you used to know in high school. And that kid definitely died three years ago.

The familiarity I feel toward her acrylic paintings is partly easy to explain: We’ve all seen some crisper version of it, as she often uses 18th century paintings of aristocratic life as her starting point. But her work also feels familiar because of its ability to evoke the kind of primal dread that is exciting and addictive. The kind of dread you can’t turn away from. The kind of dread where you don’t understand you’ve sauntered into something deadly until the teeth around you have already closed… you were just stunned by the beauty and sipping your Earl grey and then BOOM, you’re falling down the throat of the beast.

The dramatic danger, the warning, her paintings seem to emanate is made fully clear after you spend more than a scroll-click-Pin with it. In fact, the more I look at her paintings, the more they seem to melt before my very eyes. I find that darkly exciting too.

“If you’re really enjoying something you don’t need to see the end of the road, the finishing line. That’s not always going to be the ultimate triumph, you know? If you’re not enjoying the journey, the end result will be no good.”

Painter Genieve Figgis

Suggested reading:

- A Twitter Artist Makes Fun of Rich People The Cut

- Genieve Figgis: Why I Paint Phaidon

- Artist page Almine Rech gallery

- From Ireland’s Wicklow Mountains, Genieve Figgis Paints Dark Narratives of Previous Worlds Artsy

- Good Morning, Midnight New York Times