The Lincoln Park Zoo lights

John Muir was a naturalist. An archivist. A tree-hugger.

In fact, he found so much purpose in these roles, he founded the Sierra Club.

He also said this: “When we tug at a single thing in nature, we find it attached to the rest of the world.”

He viewed going out in nature as a way to “wash your spirit clean,” but can it wash our conscience? What do we do with the discomforting irony of seeing nature — primal-puncturing-jaw-to-the windpipe, moved-by-the-moon nature — in cages?

Well, we put lights on the structures around these cages and pat ourselves on the back for the job well done. We hold our mittened hands together and give thanks that we have to strangle no living thing to live free. Not anymore.

But it’s still kind of awkward to see the lioness 20 feet away drowsy eyed and dreaming of pate from a jar or a seal clinging to a plastic plant as if it were food, unable to spear a bite.

Or maybe he was just playing.

To not be so depressing — we are seeing holiday lights after all! — I decide to find pleasure in how the animals adapt to their sanctuaries, how they make them feel like home.

It’s like when we go to a hotel and claim the bed near the window and take all the pillows off but two; because that is most similar to where and how we fold into one another every other night.

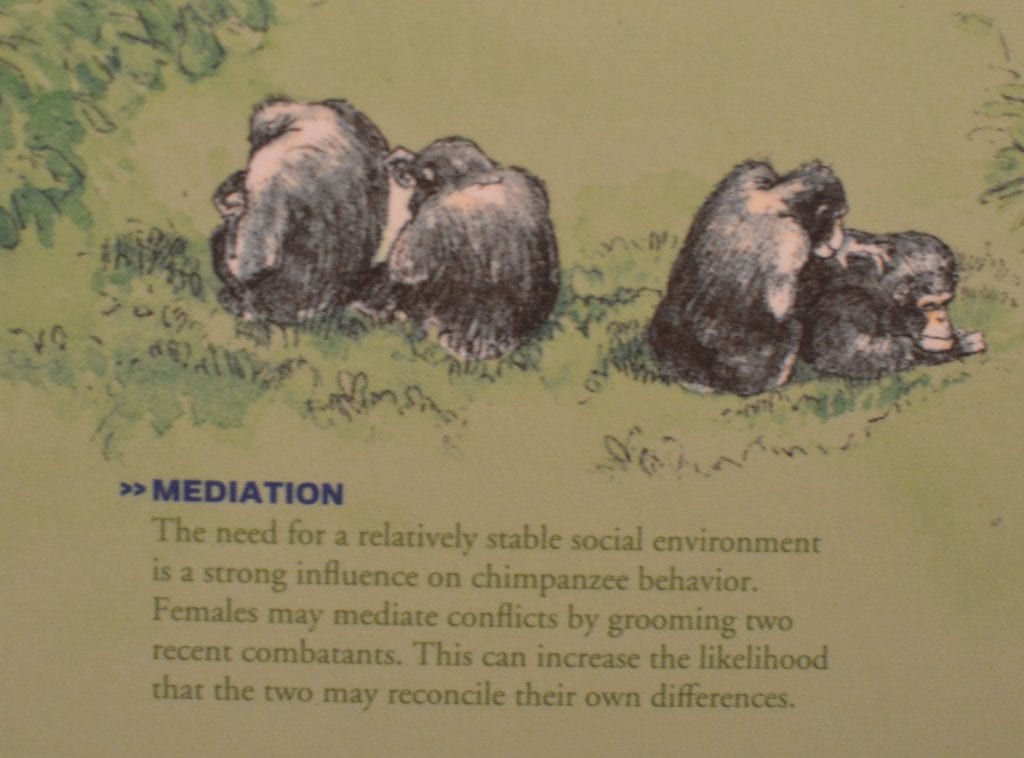

The gorillas are my favorite for this. They are so smart and full of attitude.

Chest thumpers.

Ball scratchers.

Hand holders.

Nest builders. They form little individual mattresses of leaves and sticks on which to lay. If anyone can appreciate needing to make a space for oneself, a private place to put a head about to dream — it’s a human.

Other things about them are familiar, too. And away we tug, attached to all of each other.

The writing of Rush Oh!

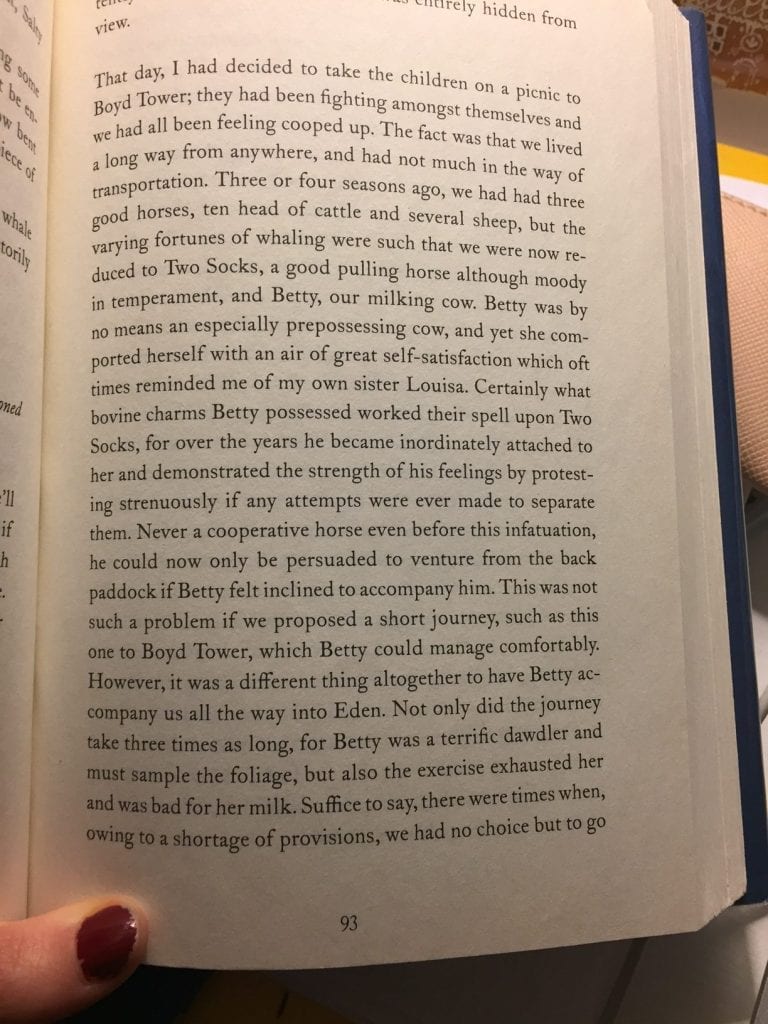

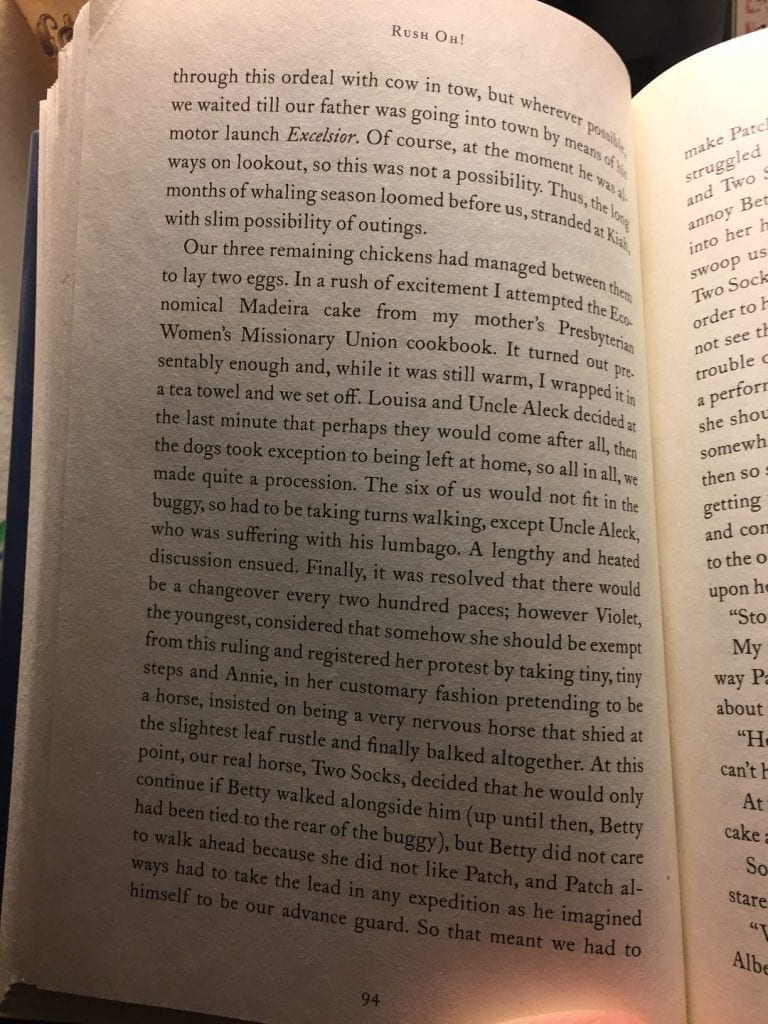

It’s hard to imagine how a book can be both brutally sad and giggle-inducing, yet here were these reviews, saying “Rush Oh!” was exactly such. It’s the fictional memoir of a daughter of a whaling family in Australia’s Twofold Bay. Loosely based on a real family, it recounts the haunting 1908 whaling season.

Here’s my favorite passage example of how the author, Shirley Barrett, nails this uncommon voice.

I learned a lot about whaling too? Who knew I would find it so interesting, especially the personalities of the Killer whales who helped the human hunters (the Killers got first dibs in the water’s depths before the carcass gassed up to the surface). Turns out there’s a real museum dedicated to these cetaceans and this incredible, dichotomous era of violence and cooperation between man and beast at Australia’s Twofold Bay. One more thing to add to the bucket list!

Survival is weird.

Snowflakes!

Are we all over the “YOU ARE NOT A SPECIAL SNOWFLAKE” retort yet?

Ugh, we should be.

Listen, you can find yourself to be special and not be entitled. You can recognize that a snowflake is one of millions but also, that when fallen into a snowy drift or peed on by a dog alongside millions of its fallen brethren, it is not so special. But does that lessen any of the fact that it has its own, made-just-for-it, swirling, spiked design?

That can still be freaking cool (it is!) and appreciated while admittedly part of a bigger picture in which one’s own personal needs or identity hold, well, a snowflake-size worth of importance.

From water to water ye shall return!

What seems more “special snowflake-y” in attitude is actually calling someone else a “special snowflake.” When someone else’s self-awareness or individuality personally offends you, I’d say you appear to be the one with deep, unwarranted entitlement issues.

The hypocrisy of the bully is never ending, though.

So to that statement, “You are not a special snowflake!”, I happily give a smile and a middle finger.

And, oh, what do you know? Look here! Staring back at me from my one finger salute to your self-righteous poo-pooing of my self-worth is my own, made-just-for-me swirly design.

I’m special snowflake af!