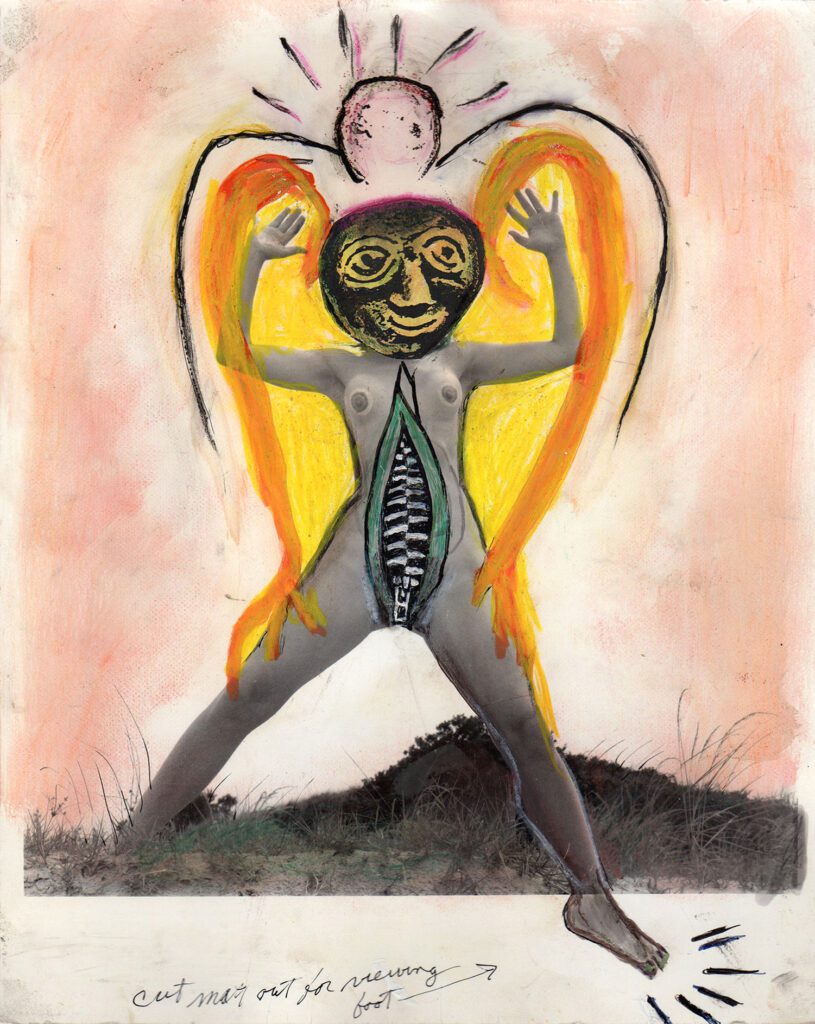

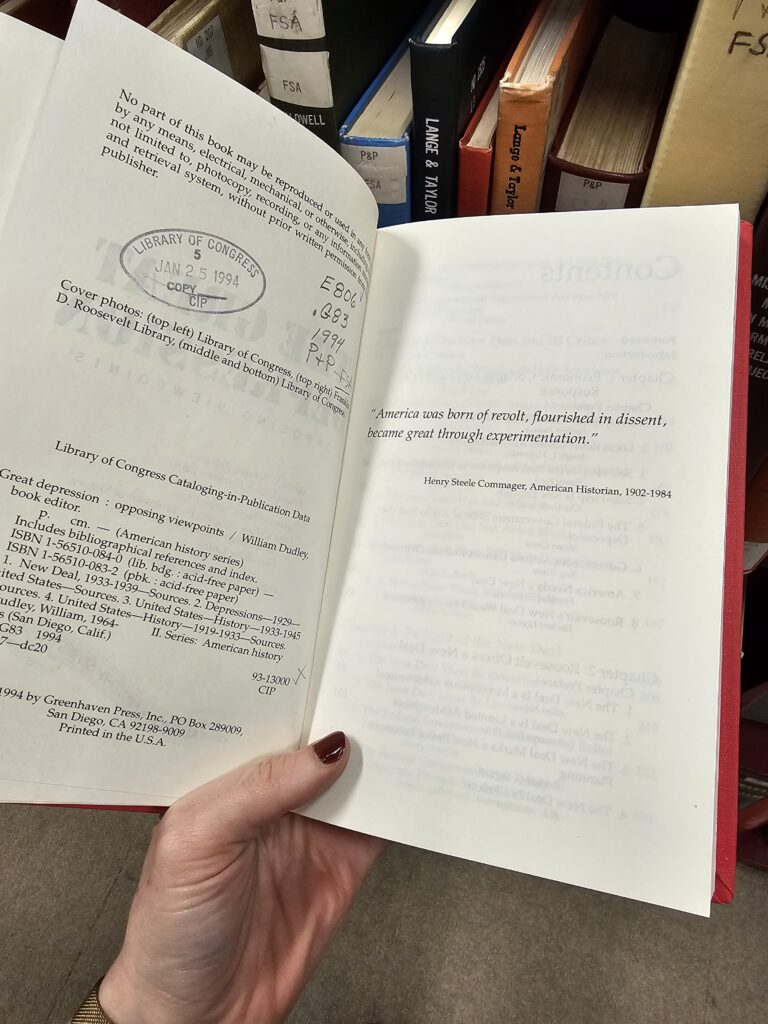

In 1969, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote a short but powerful text titled Manifesto for Maintenance Art. At the time, she was a new mother and was struck by how quickly domestic labor could eclipse any other identity she held, including that of artist.

In the manifesto, Ukeles outlines a radical distinction between two types of work:

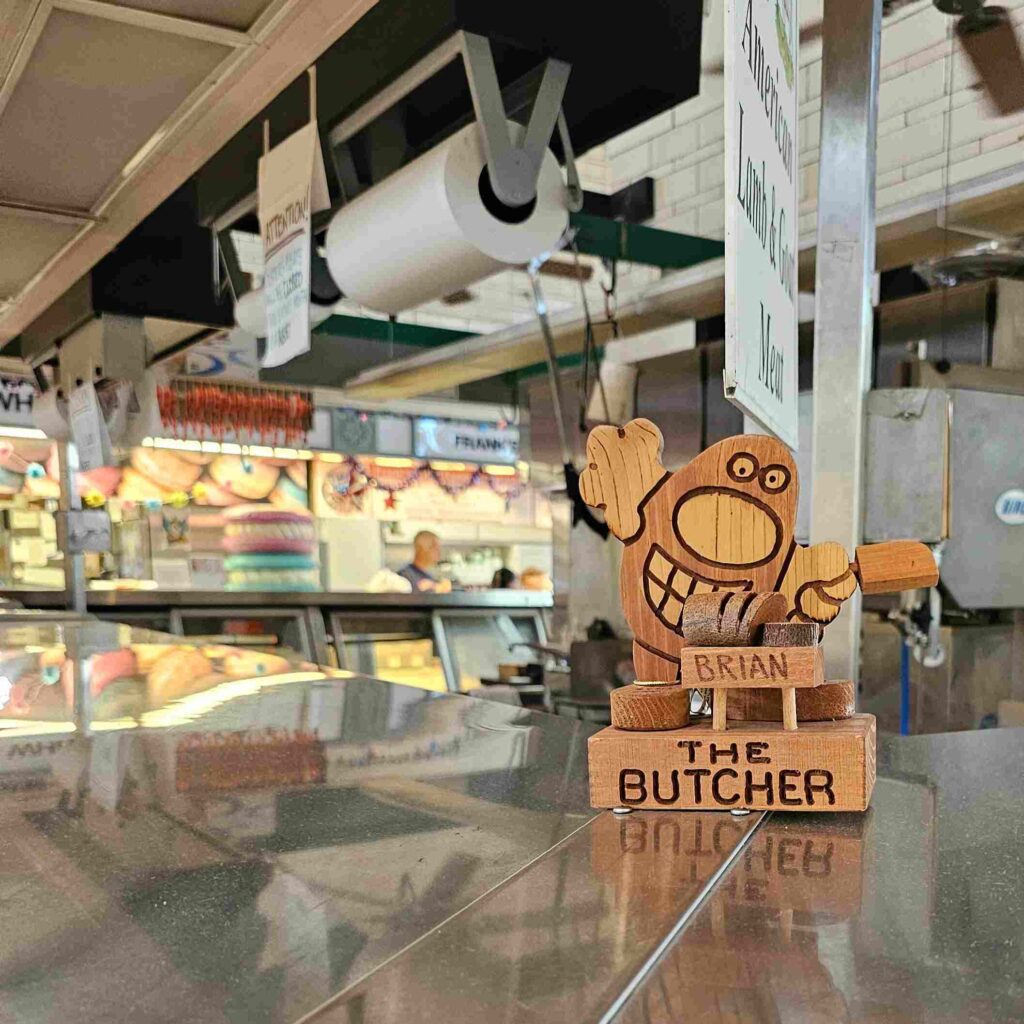

- Development work is associated with progress, innovation, and change. It’s the work our culture celebrates — building, creating, growing.

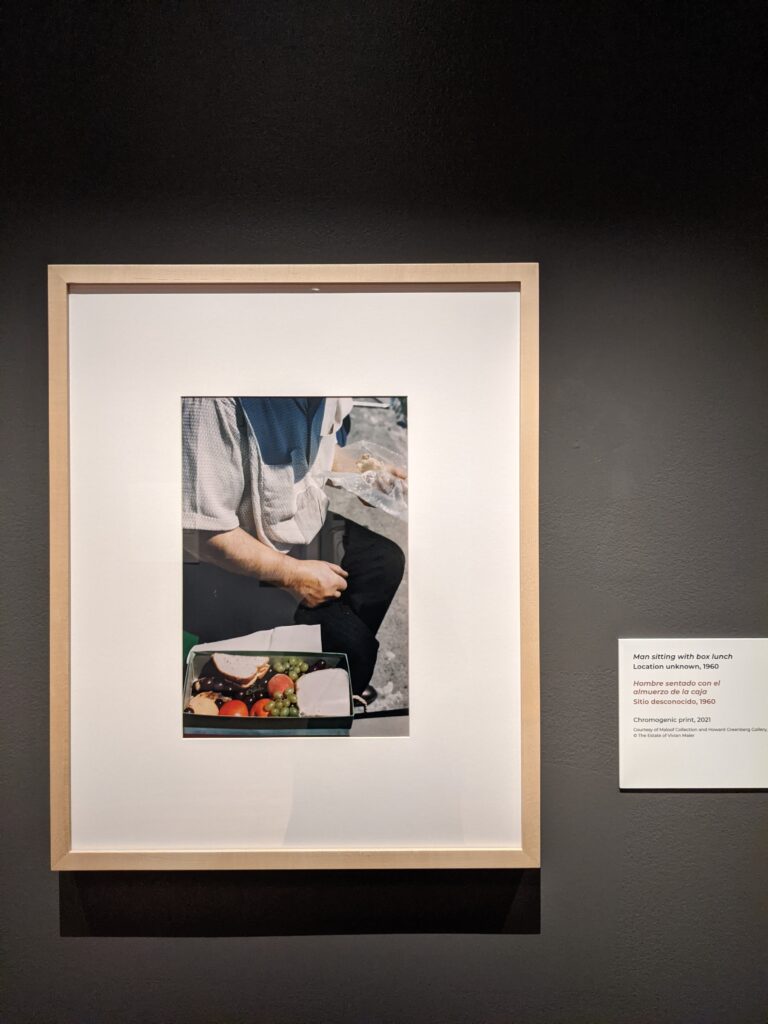

- Maintenance work, on the other hand, is everything that must be done to sustain that progress and extend the change. It’s the work of cleaning, organizing, fixing, caretaking — often repetitive and undervalued.

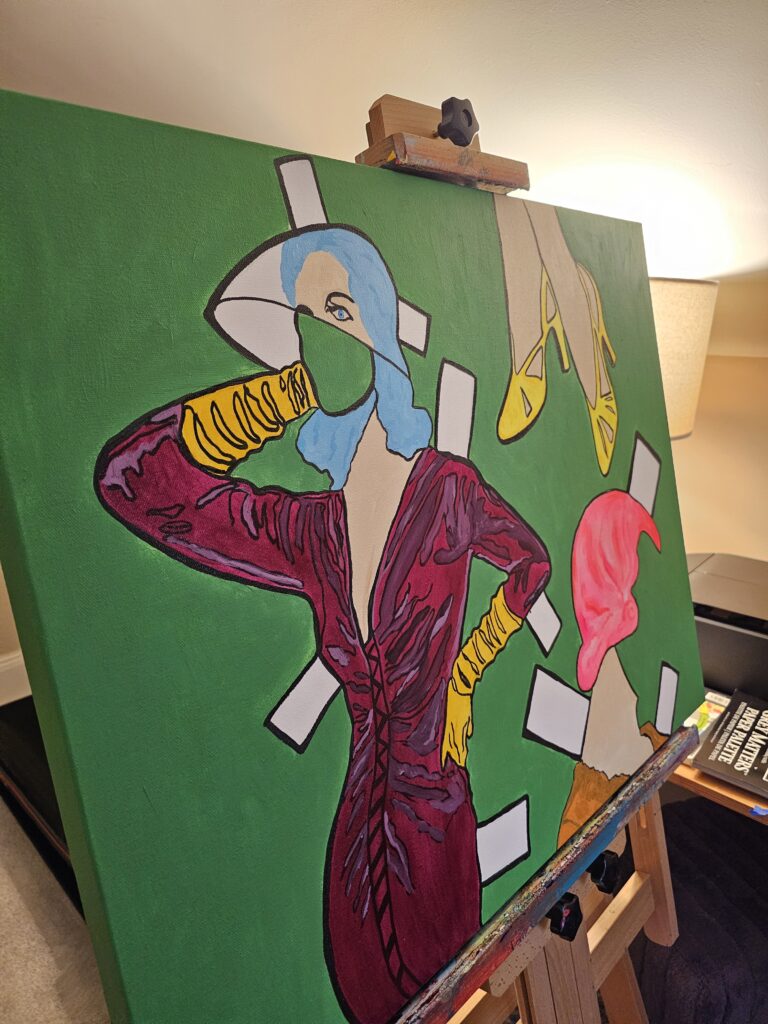

In turn, Ukeles made everyday maintenance tasks her art. She staged performances where she scrubbed gallery floors, cleaned museum steps, and shook hands with thousands of New York City sanitation workers to honor their labor. She called attention to the systems — both personal and public — that hold everything else together.

The manifesto is still a relevant challenge to hierarchy: Why should creation be considered more valuable than preservation? Why do we reward disruption but ignore the discipline it takes to sustain anything over time?

Maintenance as devotion

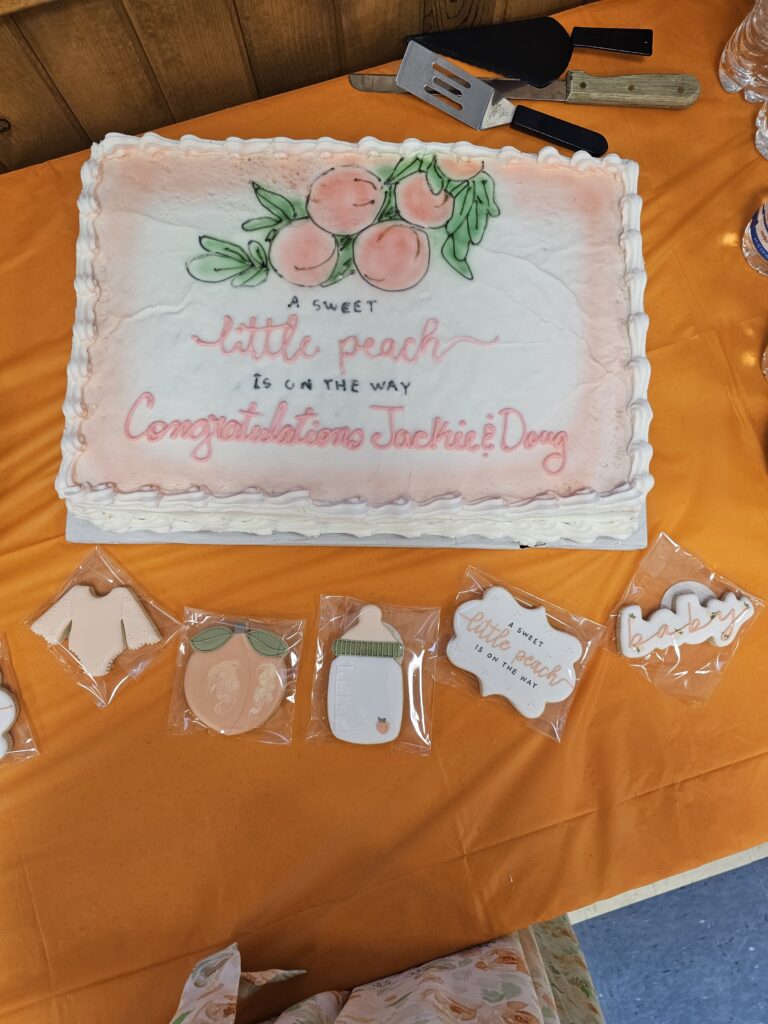

Even with all the structural advantages I have today — a career I love, a home I own, a partner who handles the bulk of weekday childcare and is fully present, from blowouts to bath time — there’s still only so much time in the day. The maintenance work hasn’t vanished just because I am happy and fulfilled.

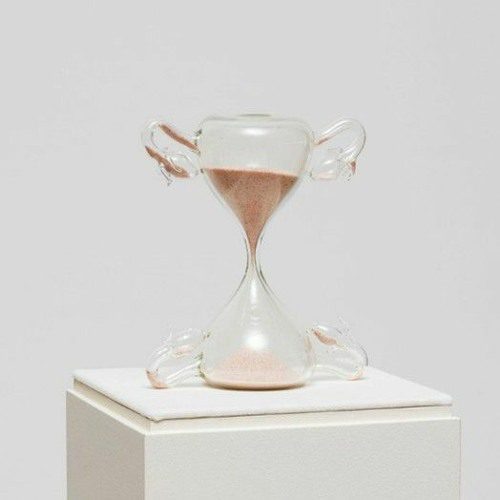

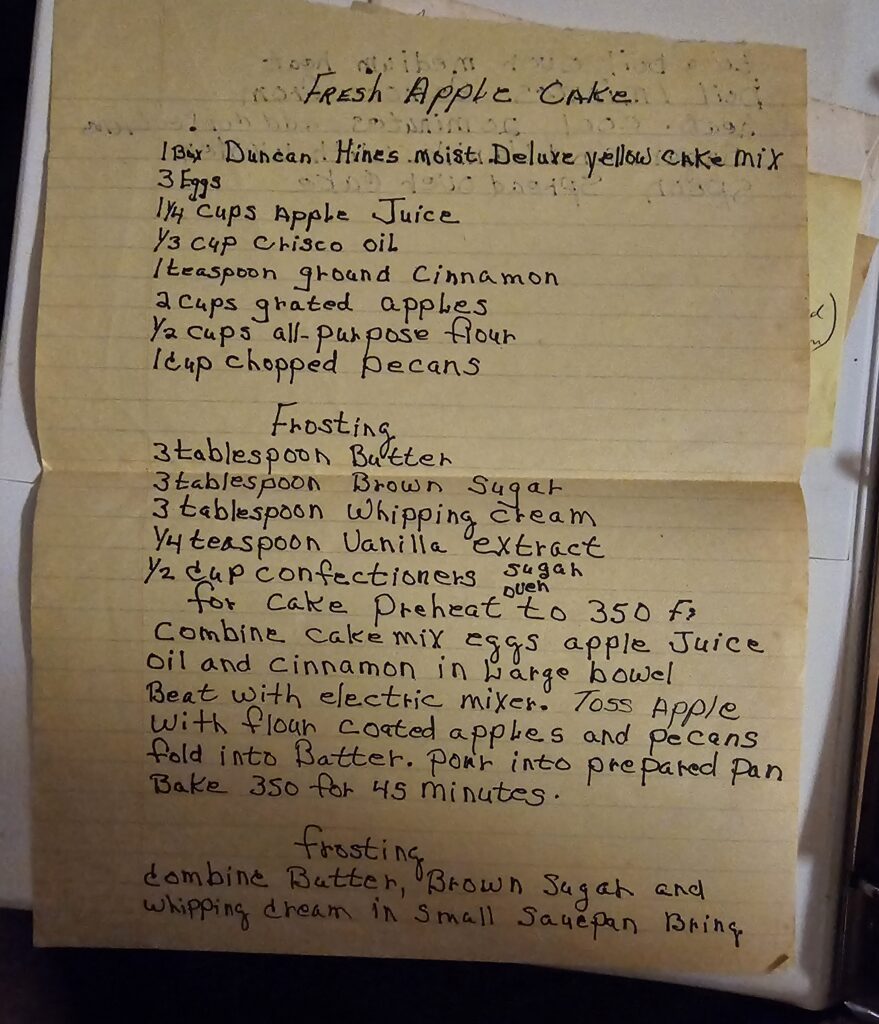

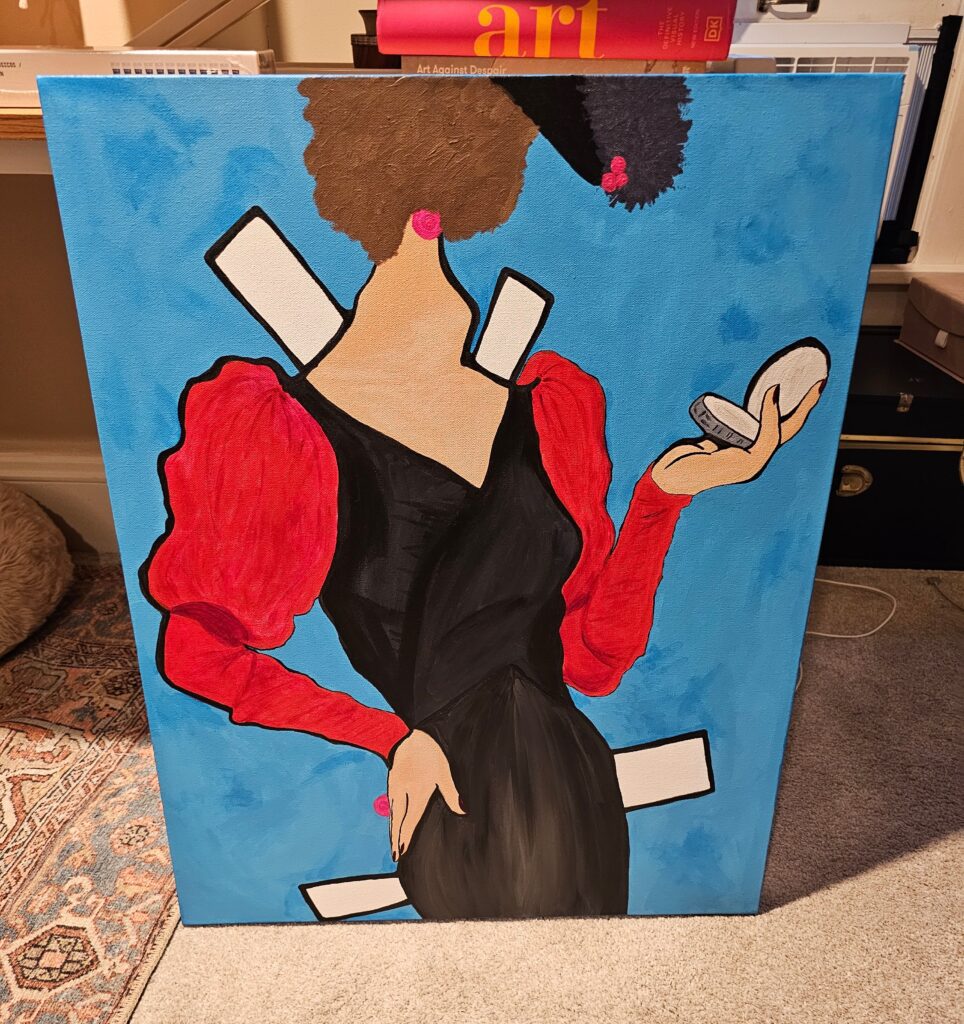

Sometimes it’s visible: dishes, laundry, making the bed, changing diapers, cleaning the litter boxes (so much poop happening in this house), ordering more of everything. But often it’s invisible, even to me. It’s the energy it takes to gear up after Alice has a restless night. The attention I have to give to my own emotional and physical landscapes (e.g., journaling, reading, working out) so I don’t spill it onto someone else. The logistical orchestration behind an hour of writing or studio time — hell, even a shower where I have time enough to shave my legs. Maintenance includes the inner work it takes to stay open, present, tethered to and in conversation with the version of myself I’m forever in the process of becoming.

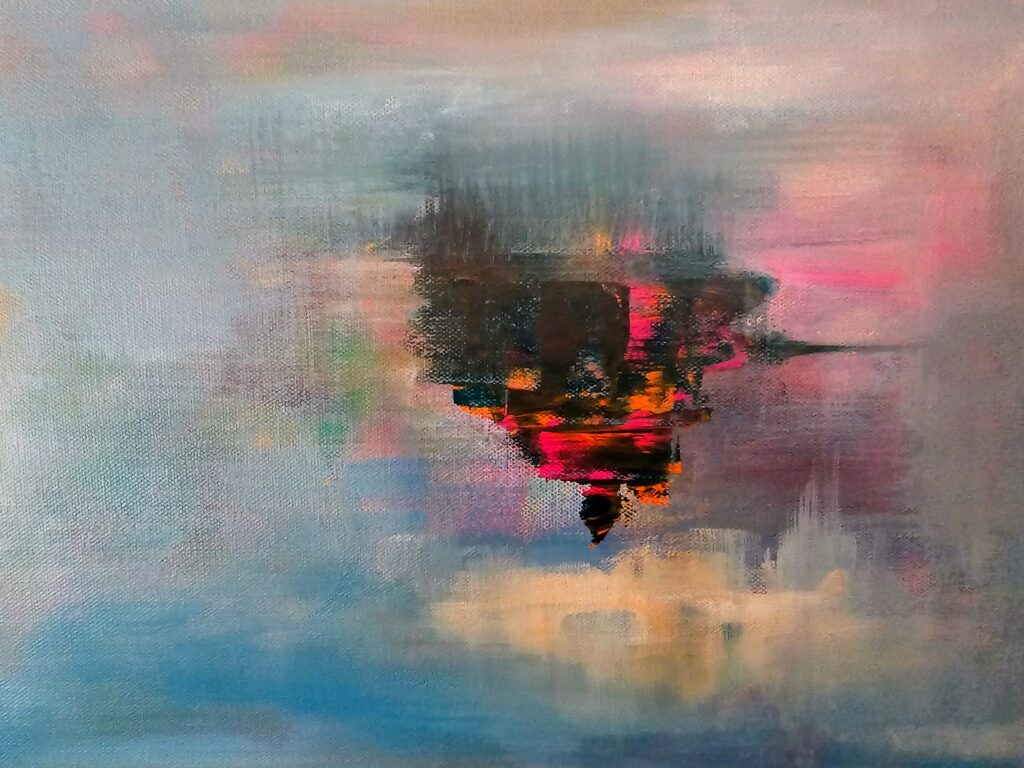

Ukeles puts language to how all of that is part of the whole. Not in a romanticized, “everything is art” way, but with a non-indulgent, matter-of-factness. She asks us to respect the maintenance of it all. And she argues that maintenance isn’t separate from creative work — it enables it. Maintenance sustains the conditions under which development can even happen. It is part of the art. Like the underbelly of the tip of an iceberg.

Her dissection of these two types of work makes me think much more positively about maintenance. Rather than all that stuff being something in my way — keeping me from doing more valuable work so I can “develop” — it helps me reframe it as an essential piece of the process.

Tending as authorship

As the year winds down, I’ve been thinking about what my “word” will be for 2026. It’s something I do with my weekly sobriety group. Each new year, we choose a word to carry with us, something to center or stretch toward.

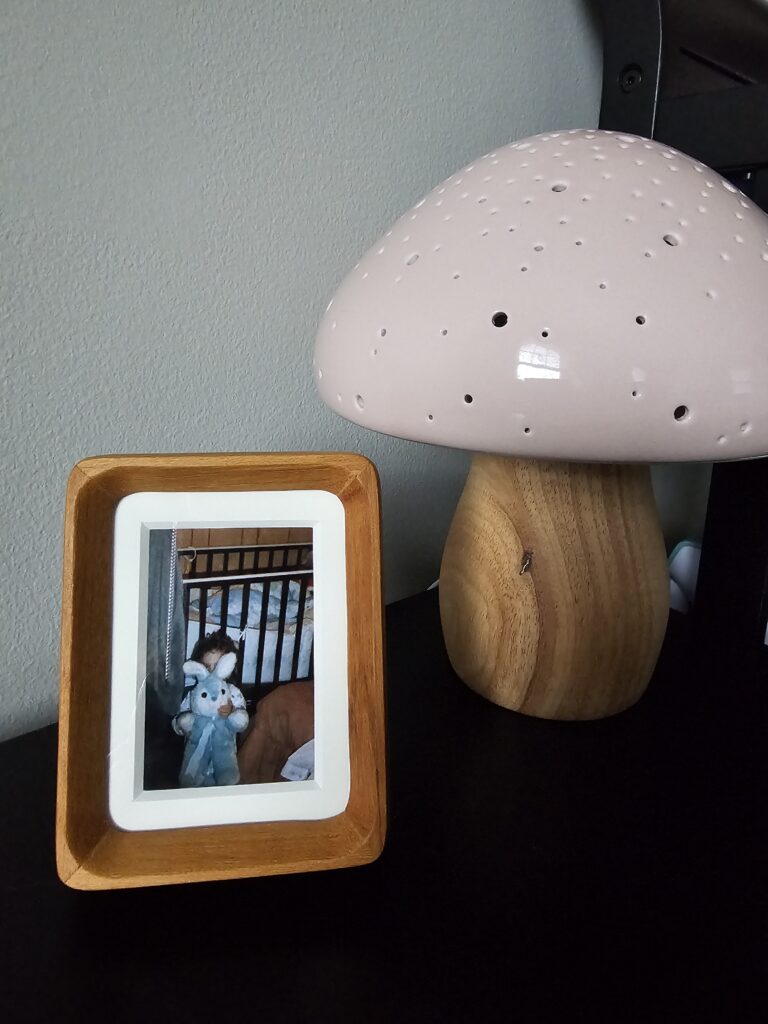

In 2025, my word was presence. I chose it knowing a newborn would change everything, and I wanted to stay rooted in the moments I’d never get back. It turned out to be the perfect word… less about perfection, more about attention. Showing up, again and again, even when I was tired or unsure or just figuring it out as we went.

Looking toward 2026, I’m resisting the urge to make it about some big, breakthrough moment. I don’t need to leap forward in my career or make a splashy new art project or transform my life. What I need, what I want, is to plant. Planting time with Alice in our backyard (where I’m trying to grow actual grass for her to run around on… harder than it sounds). Planting ideas — new ones, slow ones — that may not bloom for a while. Planting financial seeds for future stability. Planting habits that nourish the internal terrain I’m learning to tend without urgency. Stability. Repetition.

Maintenance, by another name.

I love the idea of honoring the effort it takes to hold things steady while you build something beneath the surface. That’s rebellion in a culture that constantly demands newness, loudness, proof of progress.

Ukeles saw that decades ago. She made it art. I’m making it a life.