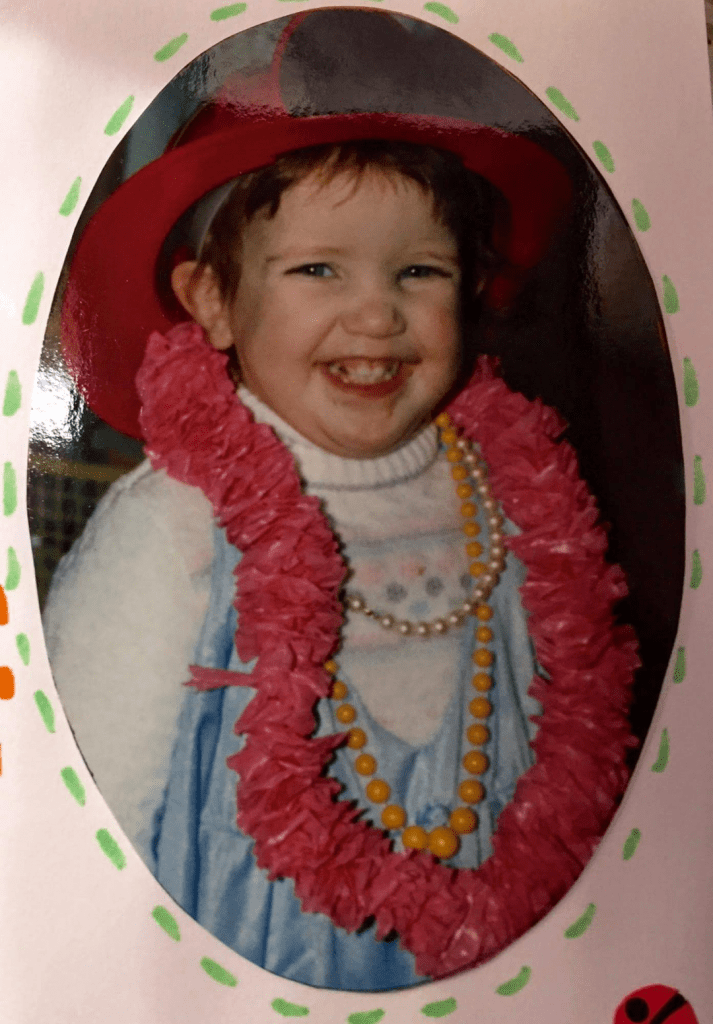

Why pink? I’ve always loved this color.

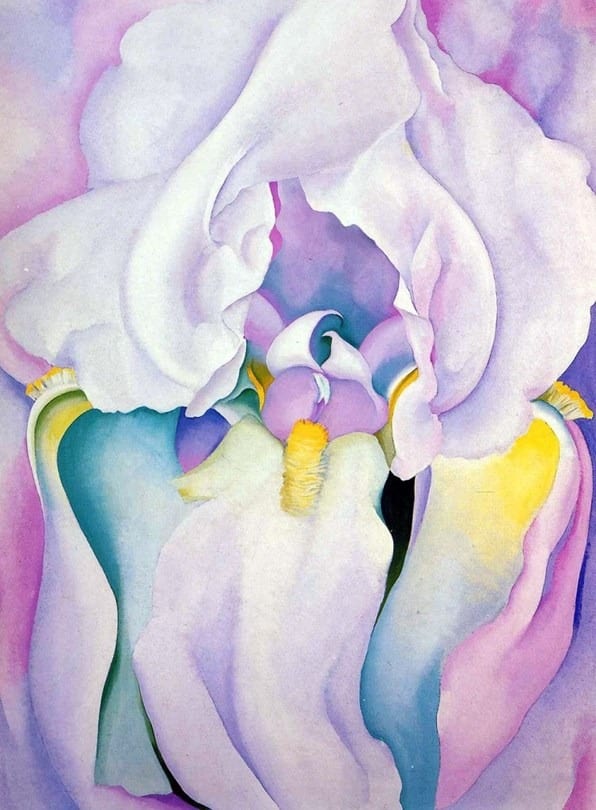

I’m drawn to every version of it. Bubblegum. Neon. Fuchsia. Pepto Bismol. Patent leather (my favorite).

My senior year of high school my mom made me a hot pink crochet blanket as a graduation gift. I loved it. For a while. Then I stored it away in the top of my closet for about a decade. Why? Pink feels authentic to me, but I became embarrassed by my love of the color.

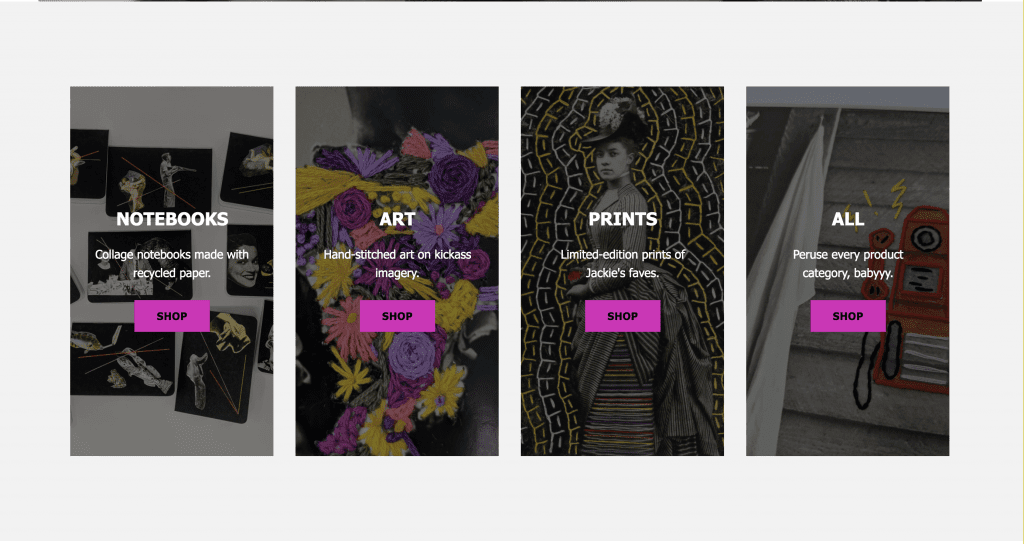

Pink seemed too conventional, too basic, too one-dimensional. That was how I perceived others perceived it. It was as if pink had already been claimed by women who weren’t like me, representing identities of the shopaholic bimbo that I wanted to distance myself from. I felt like pink had been claimed by a consumerist or sexualized society that made me feel less than valuable.

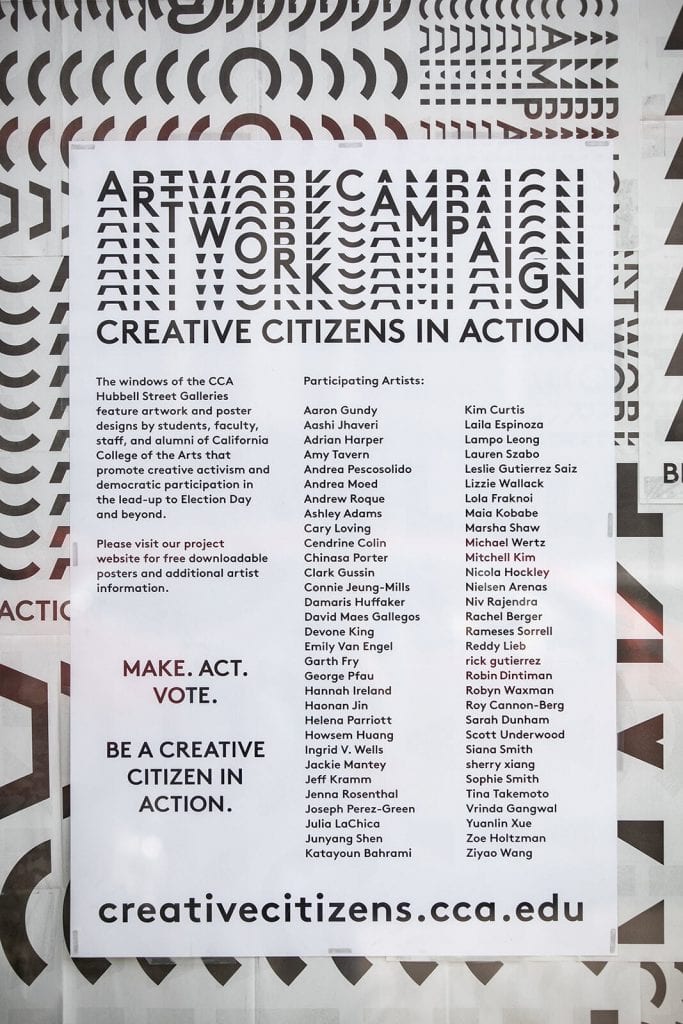

By my mid-college life I had veered away from pink’s statements, shamed by how the color has been weaponized to sell women shit and commodified to represent a whole community (i.e., who should like it and who shouldn’t). I was also cowed by the seeming conventionally of it (this, my own confused internalization of the weaponization of the color), and instead dabbled for a bit in punk rock black or wannabe-queer camo. Color and pattern are so tied to identity in that way.

Eventually, as I settled into myself, I came back around to pink, and I think it’s no coincidence that I fully embraced its powerful hold on me in my 30s, an age profound in its allowance to let me be myself. My true self. My awash in pink, sadly joyful selfhood.

Pink is a symbol of my roots, my discontent, and my self actualization.

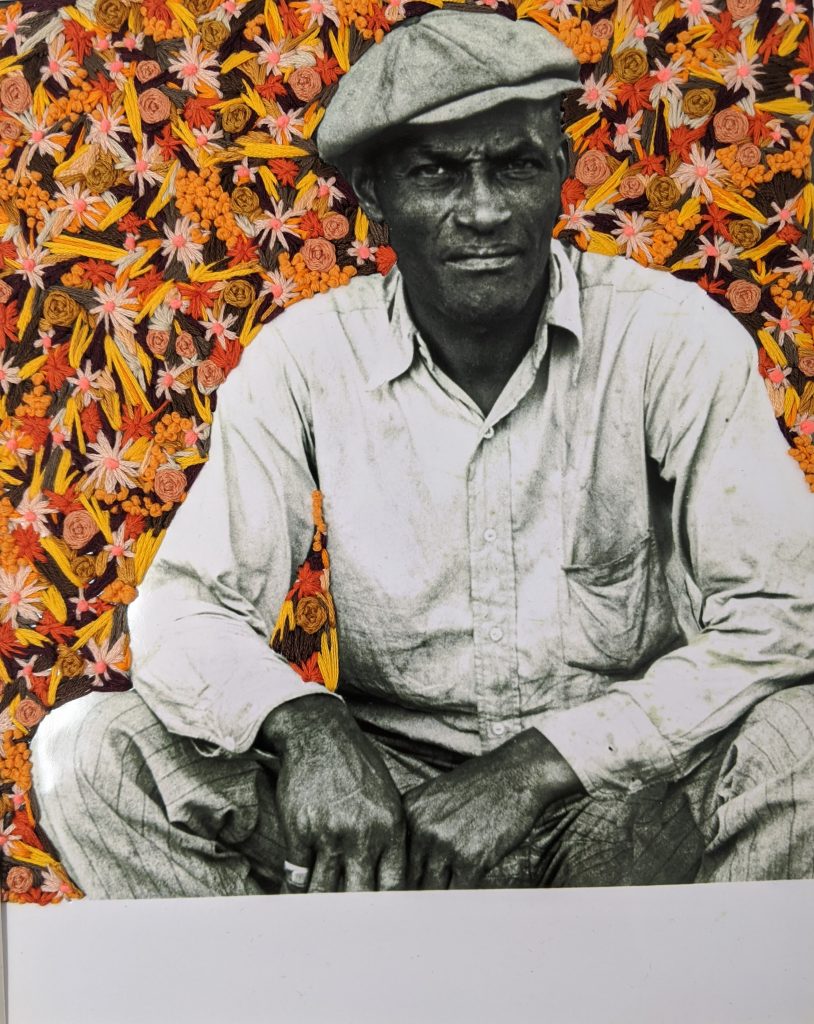

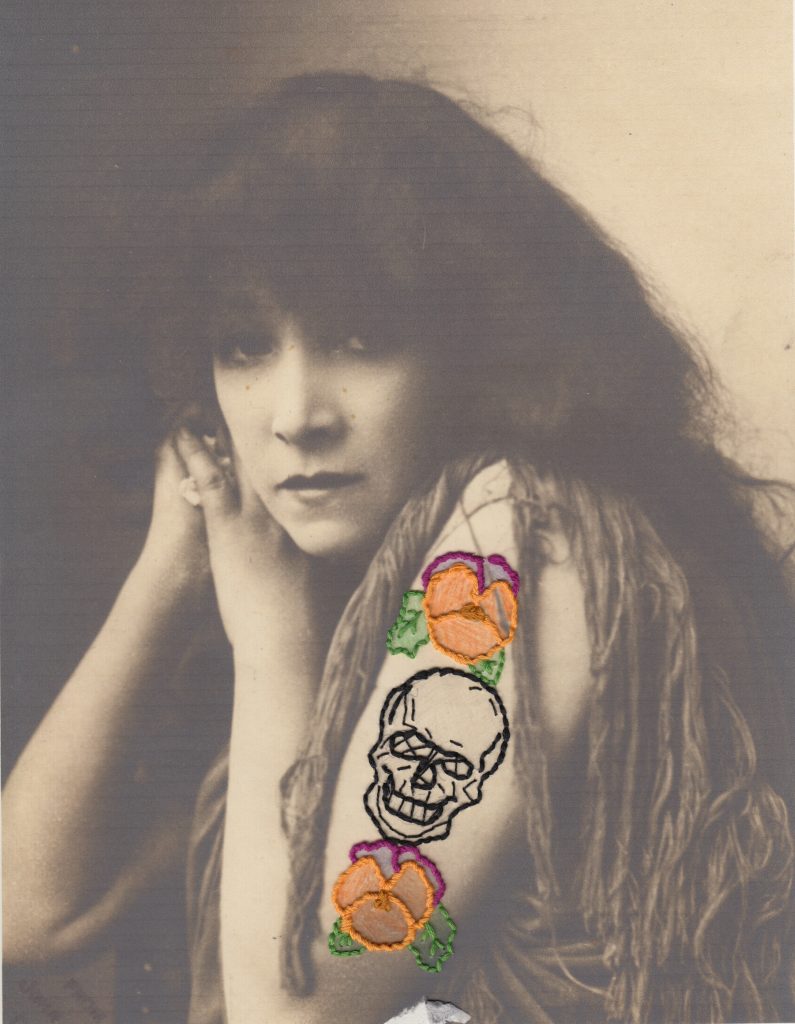

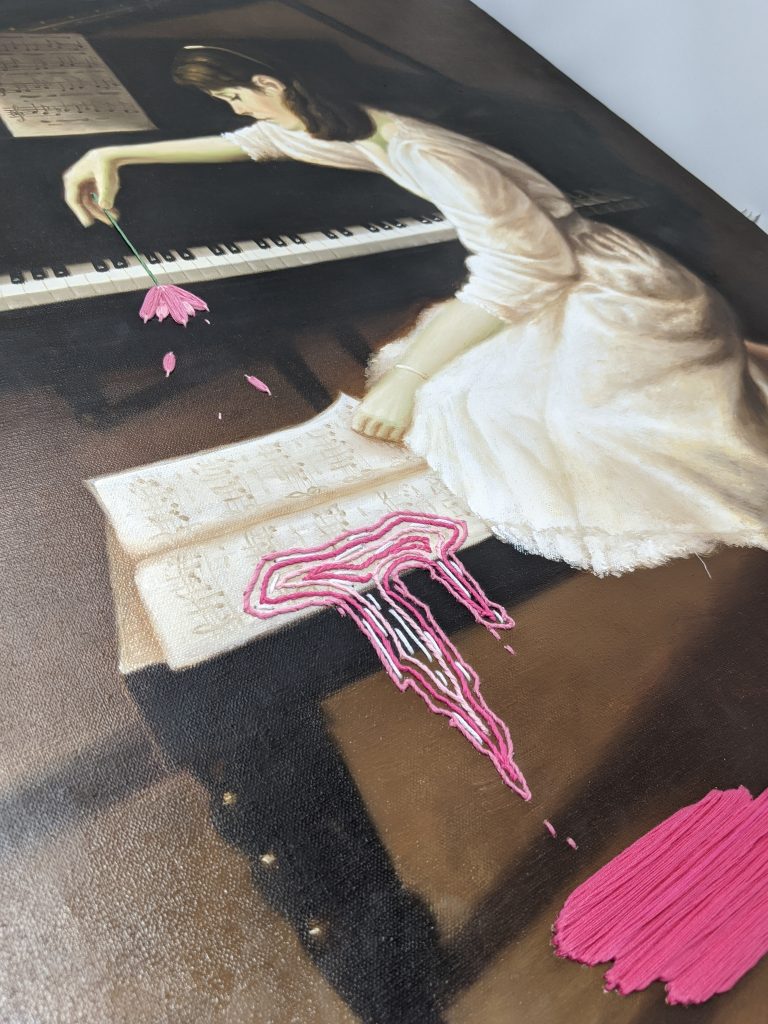

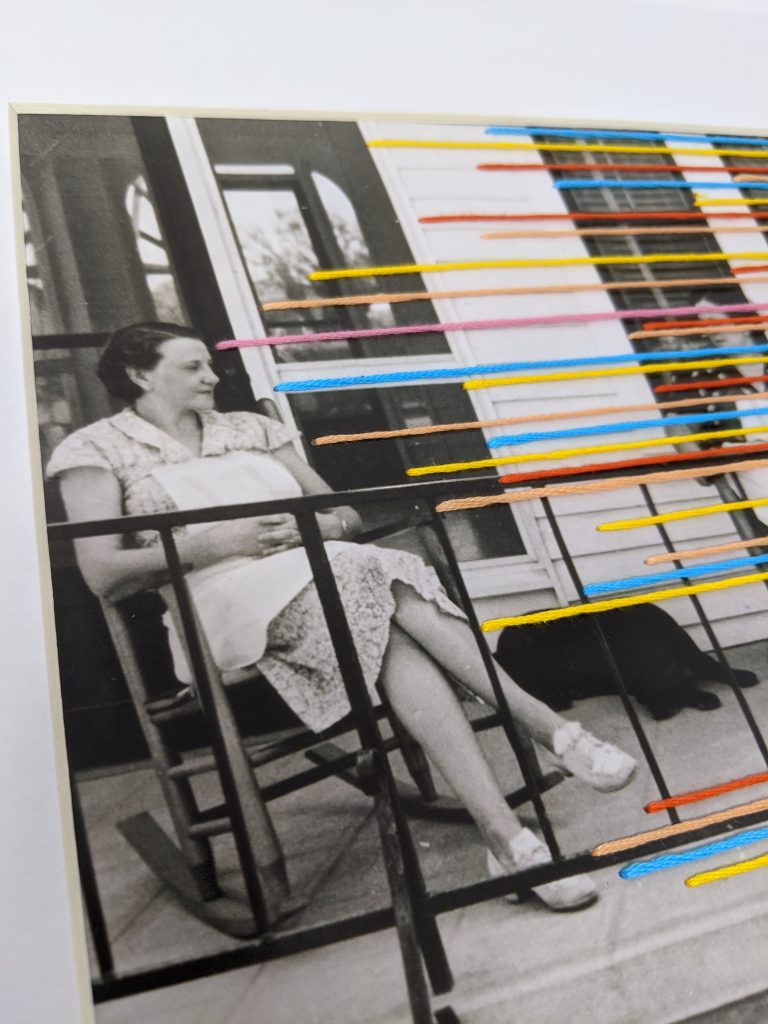

I love when men wear or like pink, but I am not too interested in using the color as an obvious gender statement in my artwork, though it probably can’t be unthreaded from that experience in a small capacity. No, I use it in my artwork as a reclamation of the color individually. Pink is powerful. I don’t find it feminine necessarily, but I myself am feminine and find power in being feminine—and power in accepting my femininity.

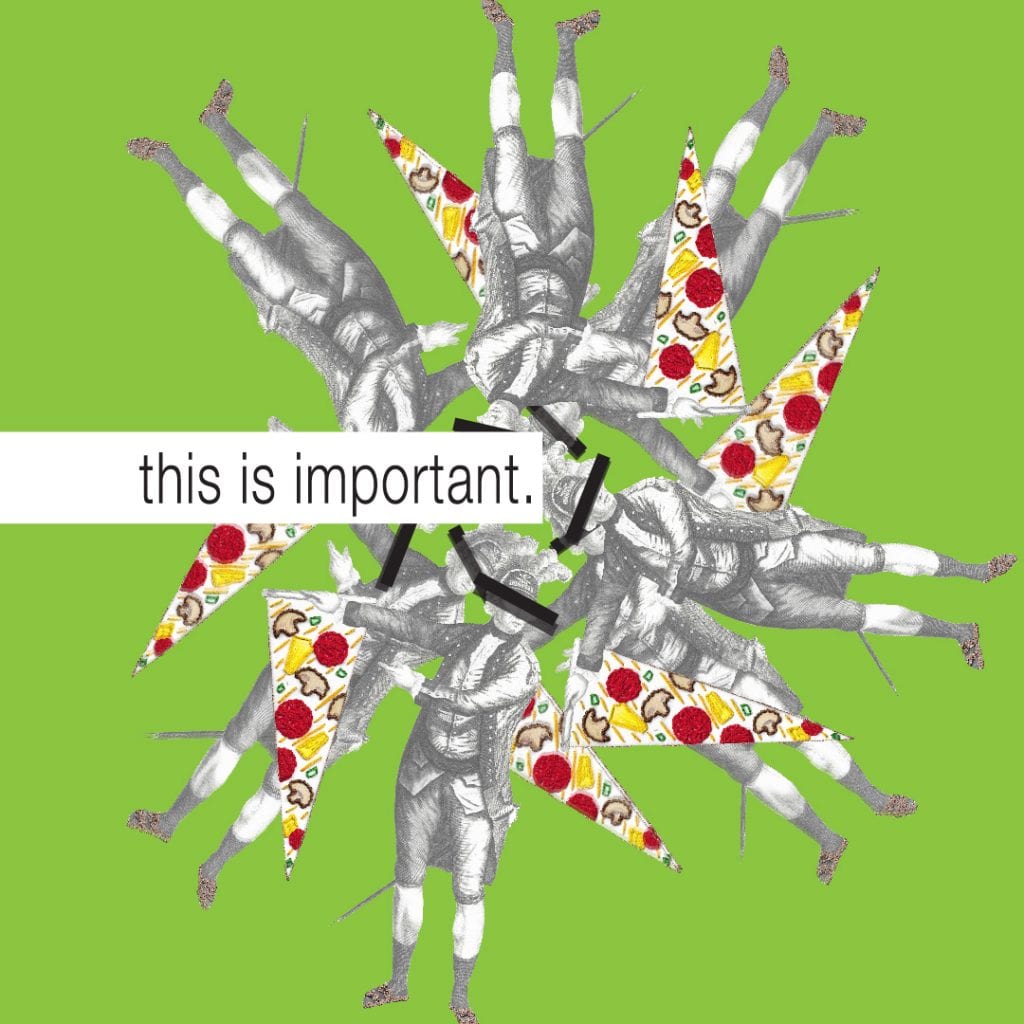

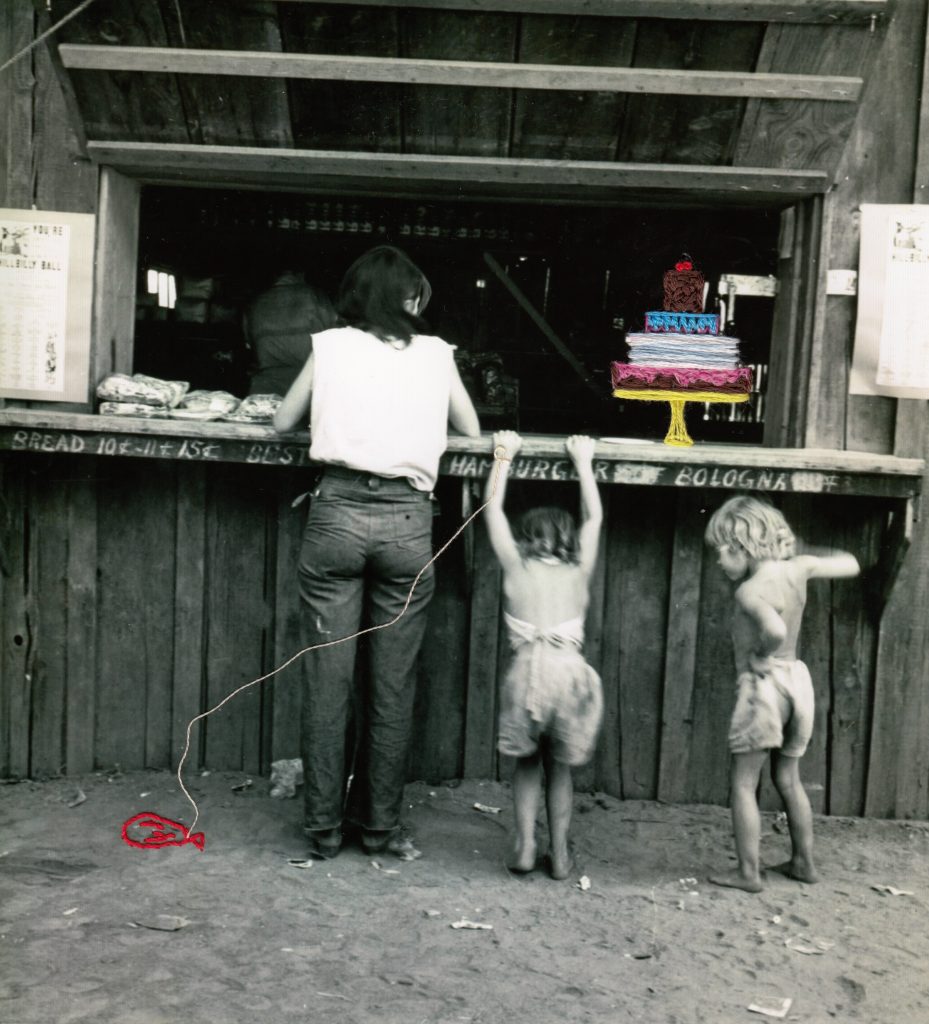

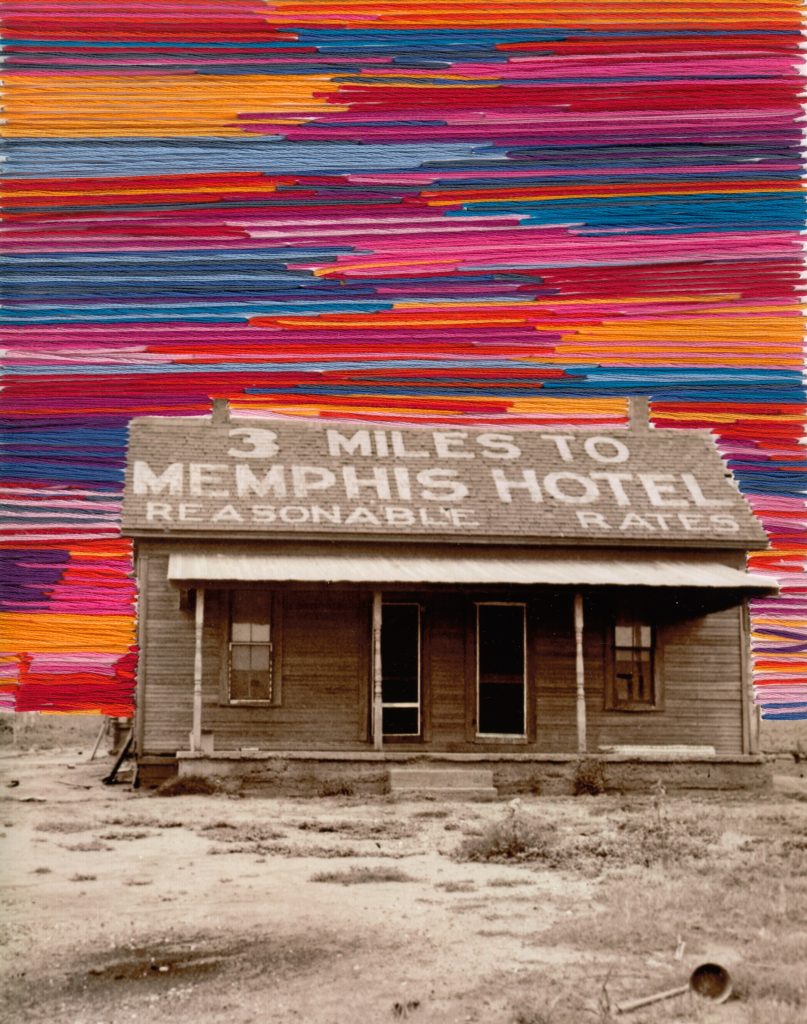

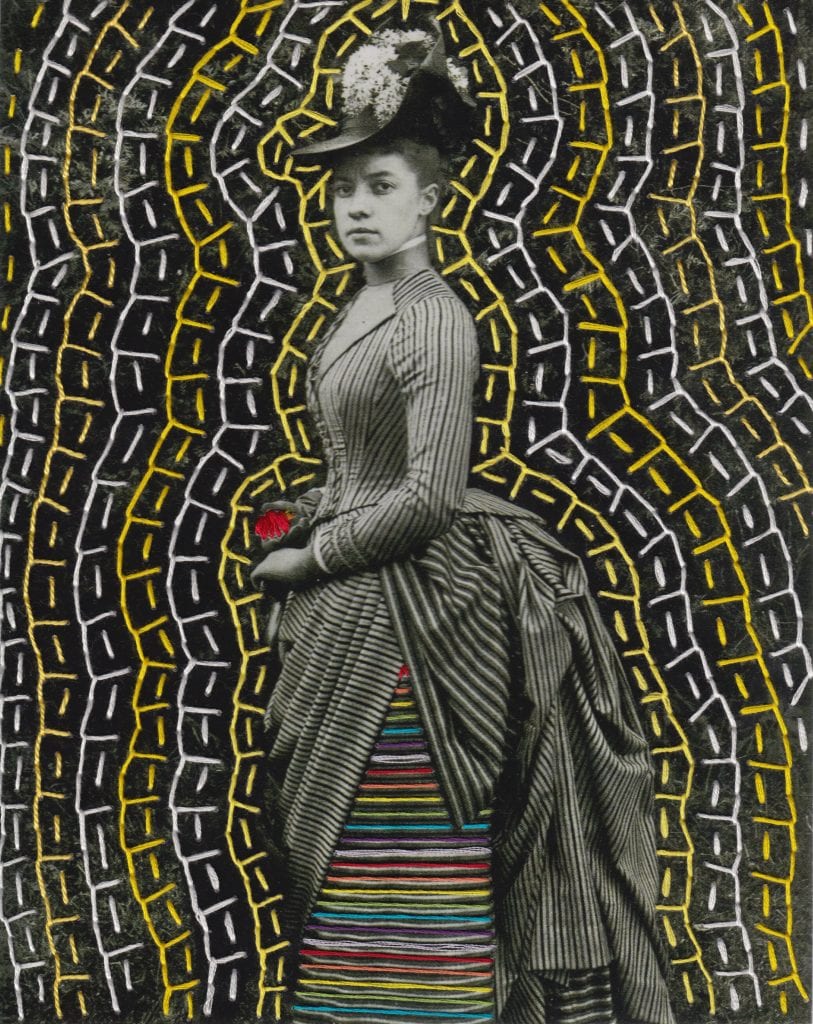

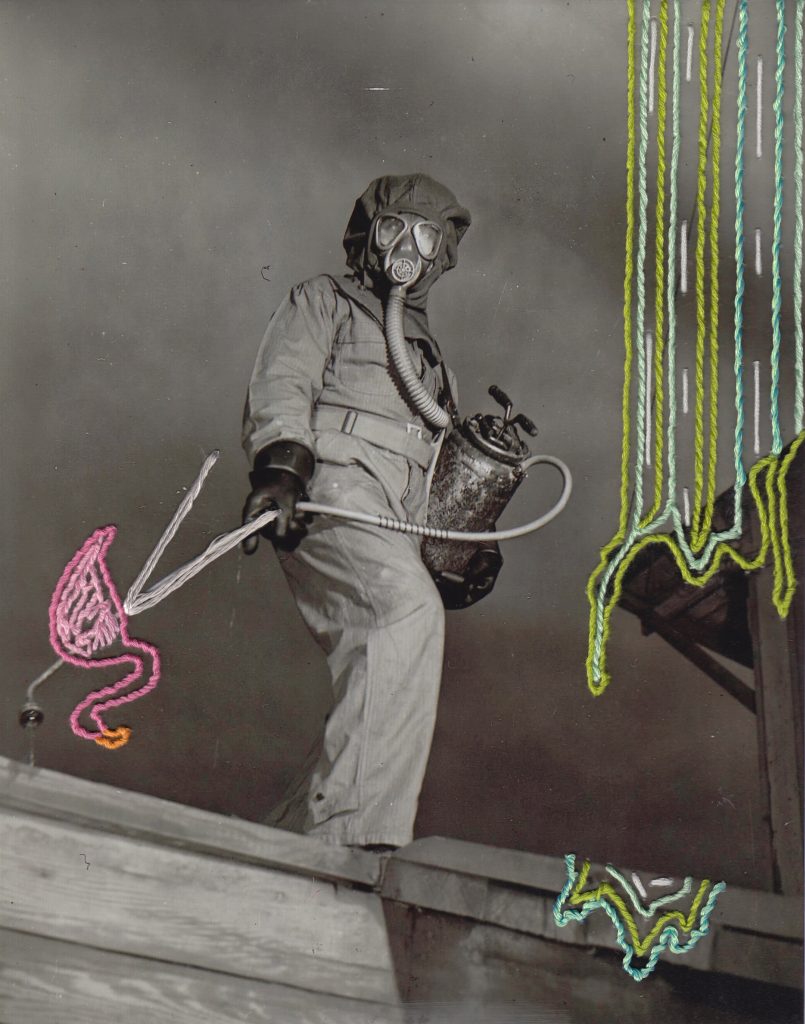

As an artistic element, pink makes anything and everything pop. Pink is a bold choice. It draws your eye and doesn’t let you go. I like that it’s still a bit divisive. It is the most stereotyped hue, as far as non-bodily pigment is concerned.

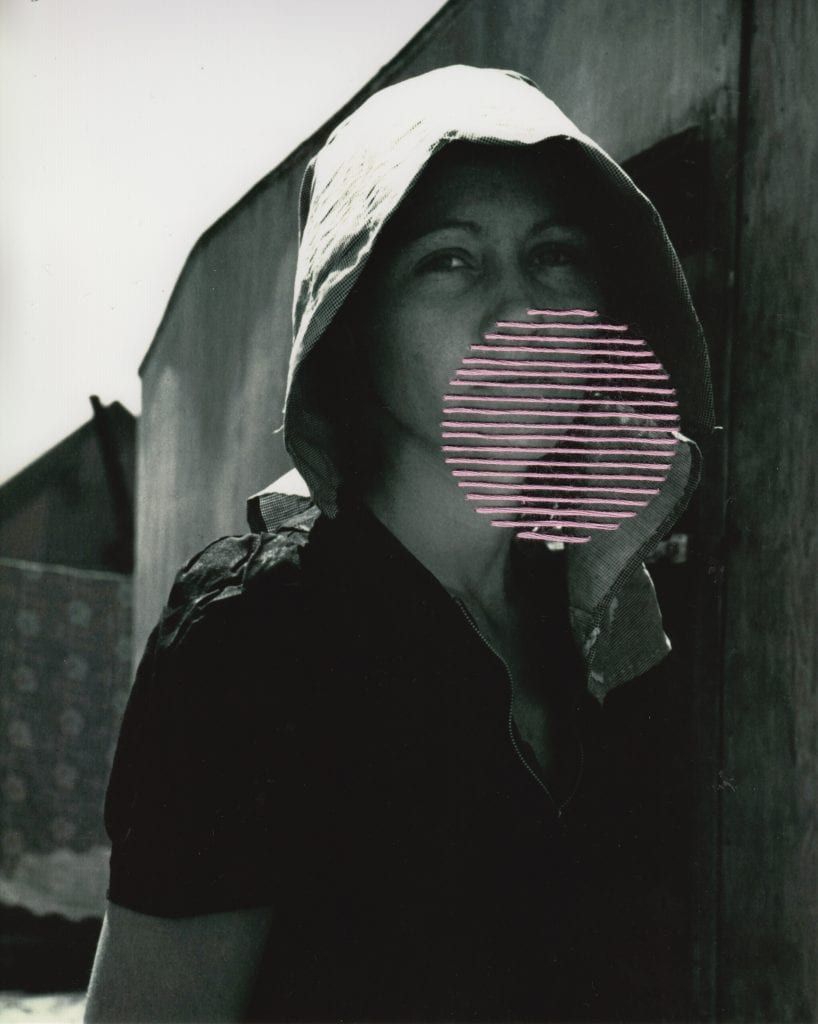

Pink draws attention to itself. Pink makes you look. Pink says, “I am not what you think I am… even though you are looking at me because you think you know precisely what you think I am.”

Pink in an artwork makes you confront something inside yourself.

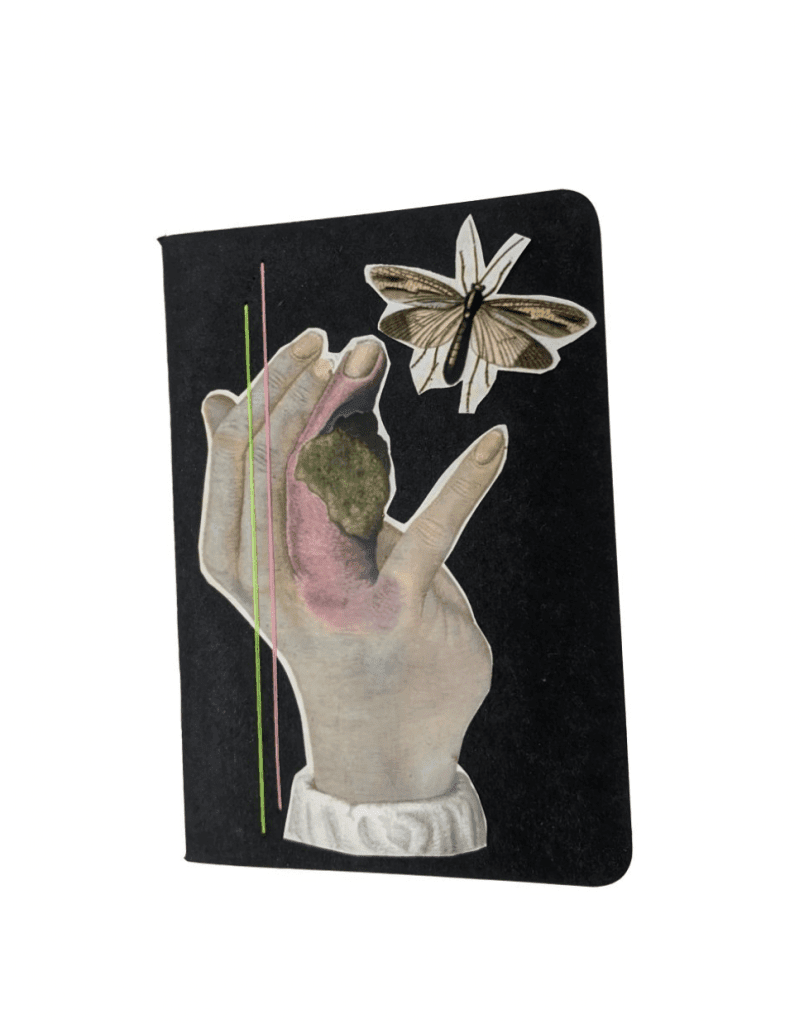

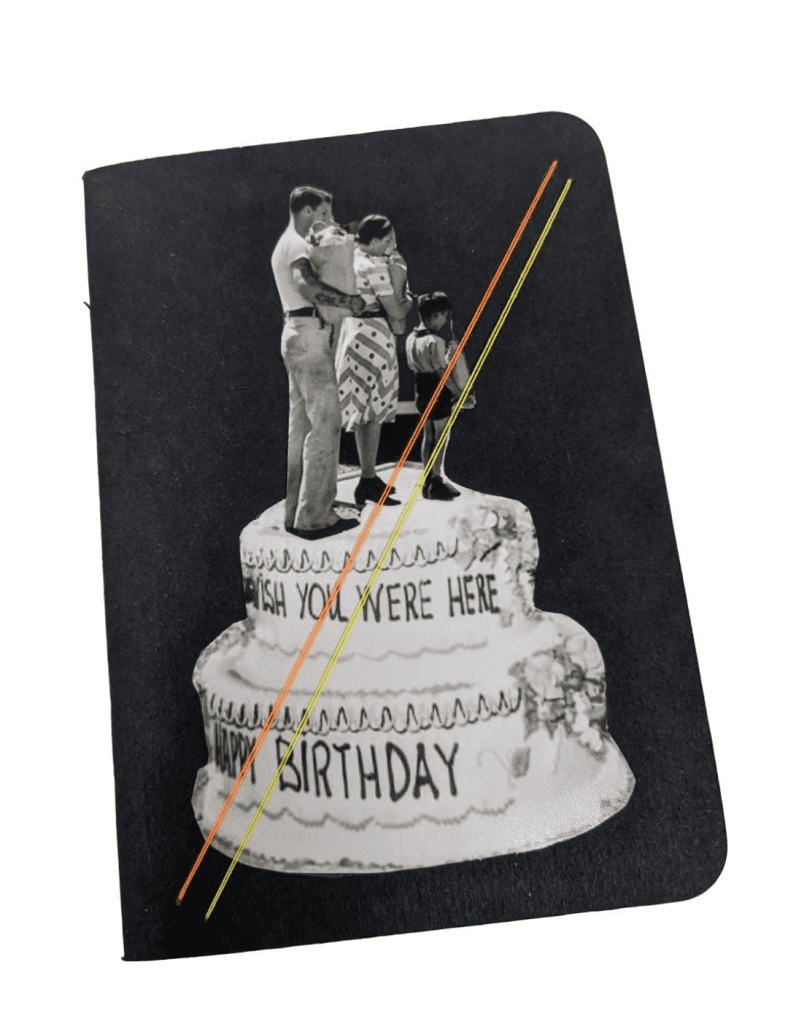

That something could be big or small, upsetting or comforting. Doesn’t matter. The confrontation is what’s important. A confrontation is a question that makes you pause. It can be as small as a stitch, or as big as an elephant. A confrontation is a question that you’ll answer almost immediately with your intuition. That’s what I’m interested in. The naturalness, primality, invoked by such an unnatural color.

Pink is a loaded adjective as much as it is a color. It is something we culturally face everyday so we’re bound to have associations with it.

Pink cloud in sobriety refers to the typically short period of euphoria that some people feel soon after quitting their drug of choice.

Pink tax is the term for how women are nickel and dimed on toiletry products made for their gender.

Pink line(s), one or two depending on your situation, is what we look for on pregnancy tests as the minutes tick by.

Can’t we just like something? Sure, but what we like has connotations, meanings, and layers. I don’t judge these. Just find it interesting. When we confront our connotations, meanings, and layers as individuals and as a whole, nonjudgmentally, we are closer to making change.

In the path from girlhood to adolescence to adulthood, the color identity shifts along with one’s self and understanding of their persona and place in the world.

Assumptions can be made. Let them.

What we like can change. Let it.

Who we are can change. Let’s.

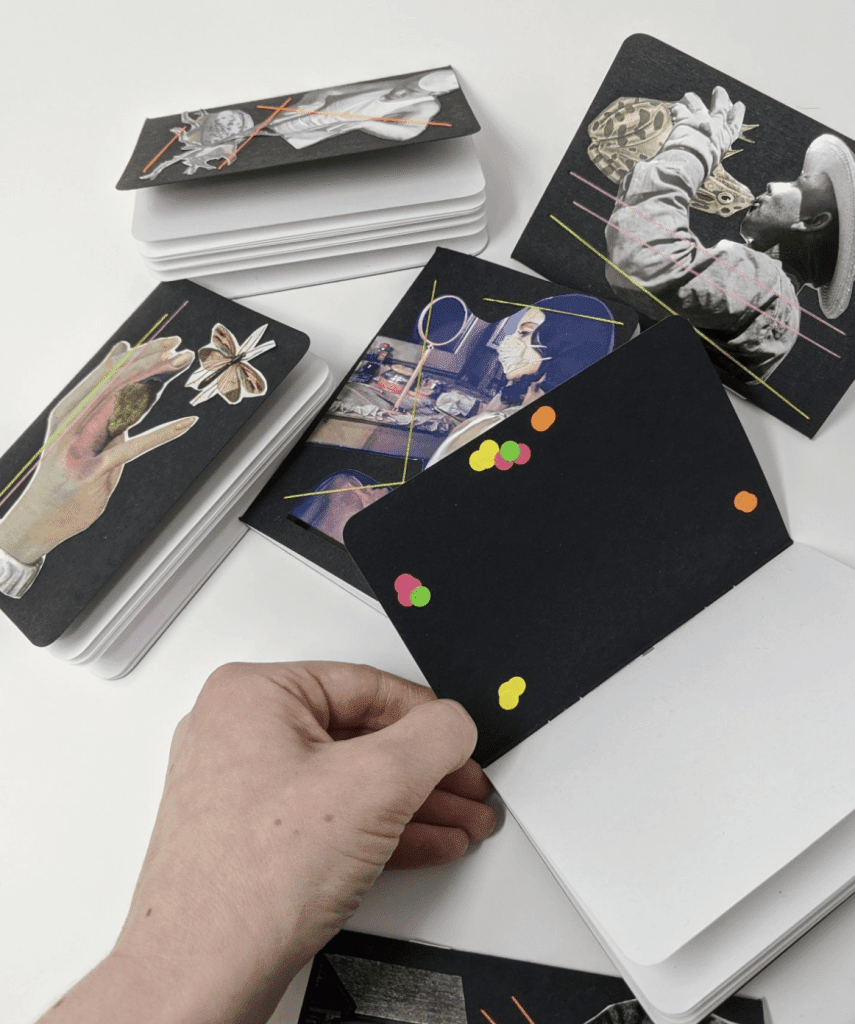

The color though. The color never changes. And maybe that’s it. Maybe pink is some form of—some outlet for—controlling the narrative of my own life. Seeing my self, my life, my color for what it truly is: Whatever I make of it.

And I want to make it beautiful, fun. I want to make it pop.