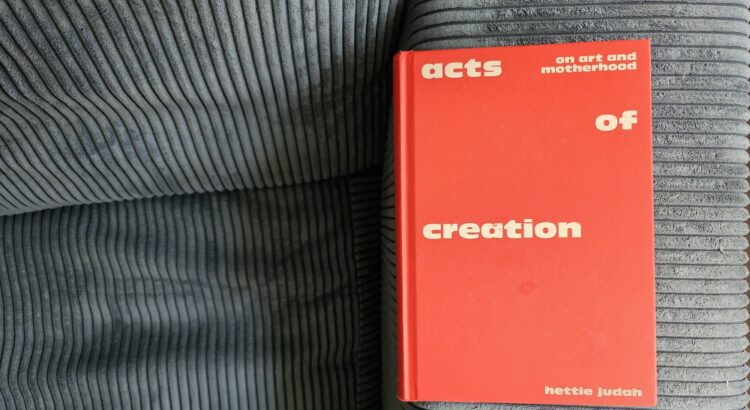

I bought the book Acts of Creation: On Art & Motherhood about a month before my due date, hungry for some kind of map for the long, unpredictable years of living as both an artist and a mother. I needed someone to tell me the two could grow in the same soil without one starving the other.

Written in 2024 by British art critic and writer Hettie Judah, Acts of Creation began as part of Judah’s research and advocacy effort aimed at challenging the art world’s structural barriers to caregiving — a project awesomely titled “How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and other parents).” Judah dismantles the myth of the solitary genius by centering the experiences of artist-mothers across decades and disciplines, drawing on interviews, artist statements, and art history. The result is part manifesto, part oral history, part cultural critique — a book that documents both the sacrifices and the radical reimaginings that happen when artmaking and mothering are allowed to co-exist.

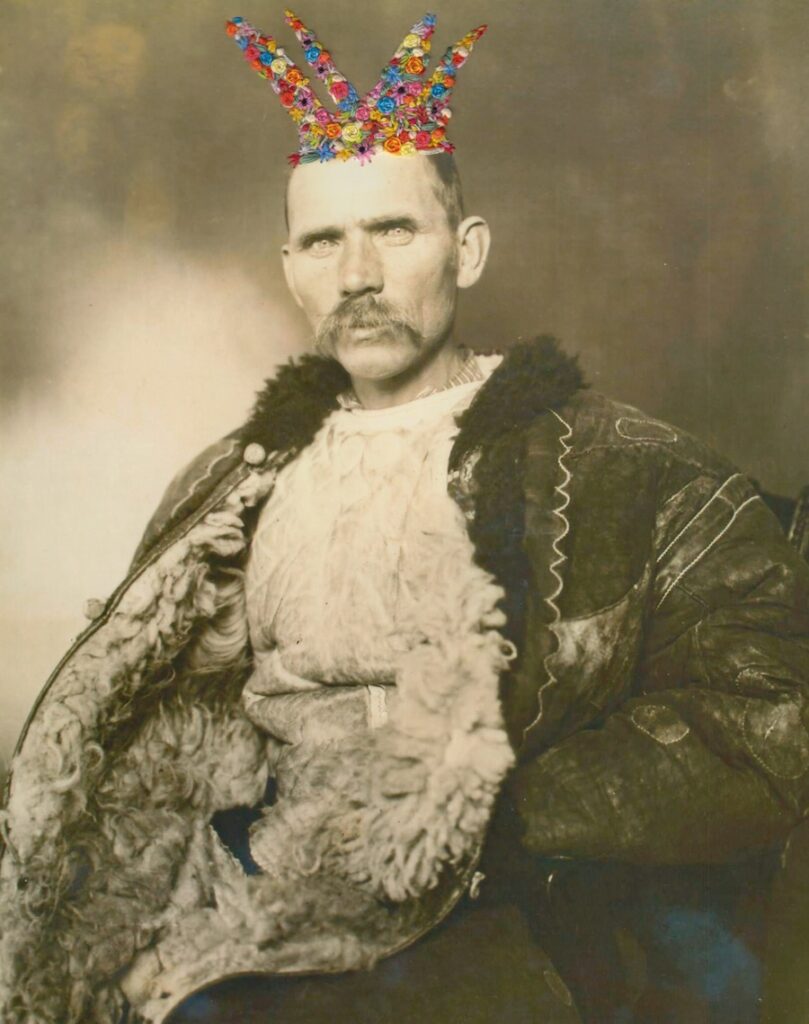

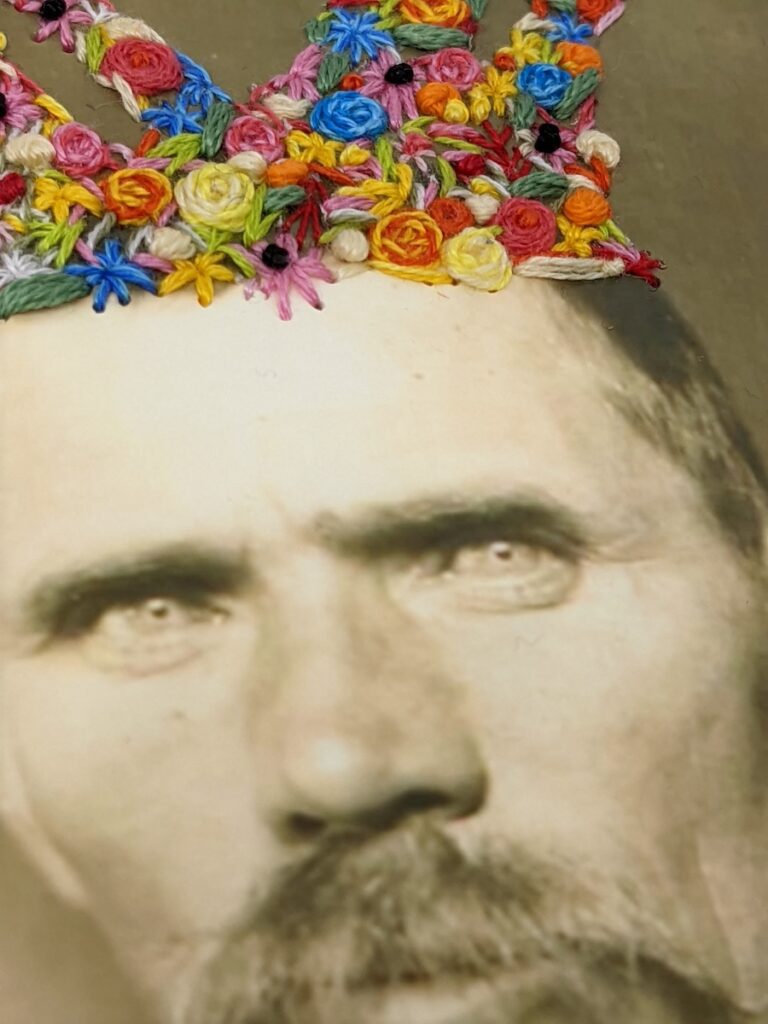

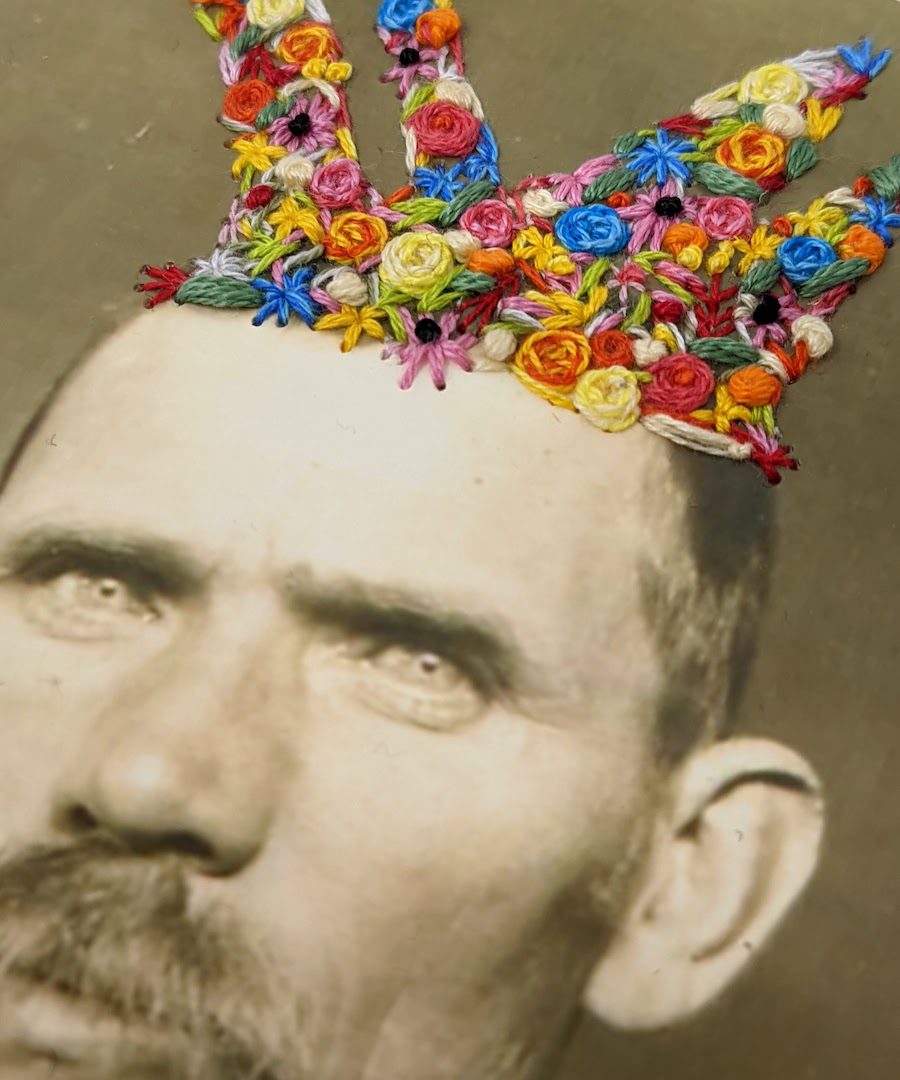

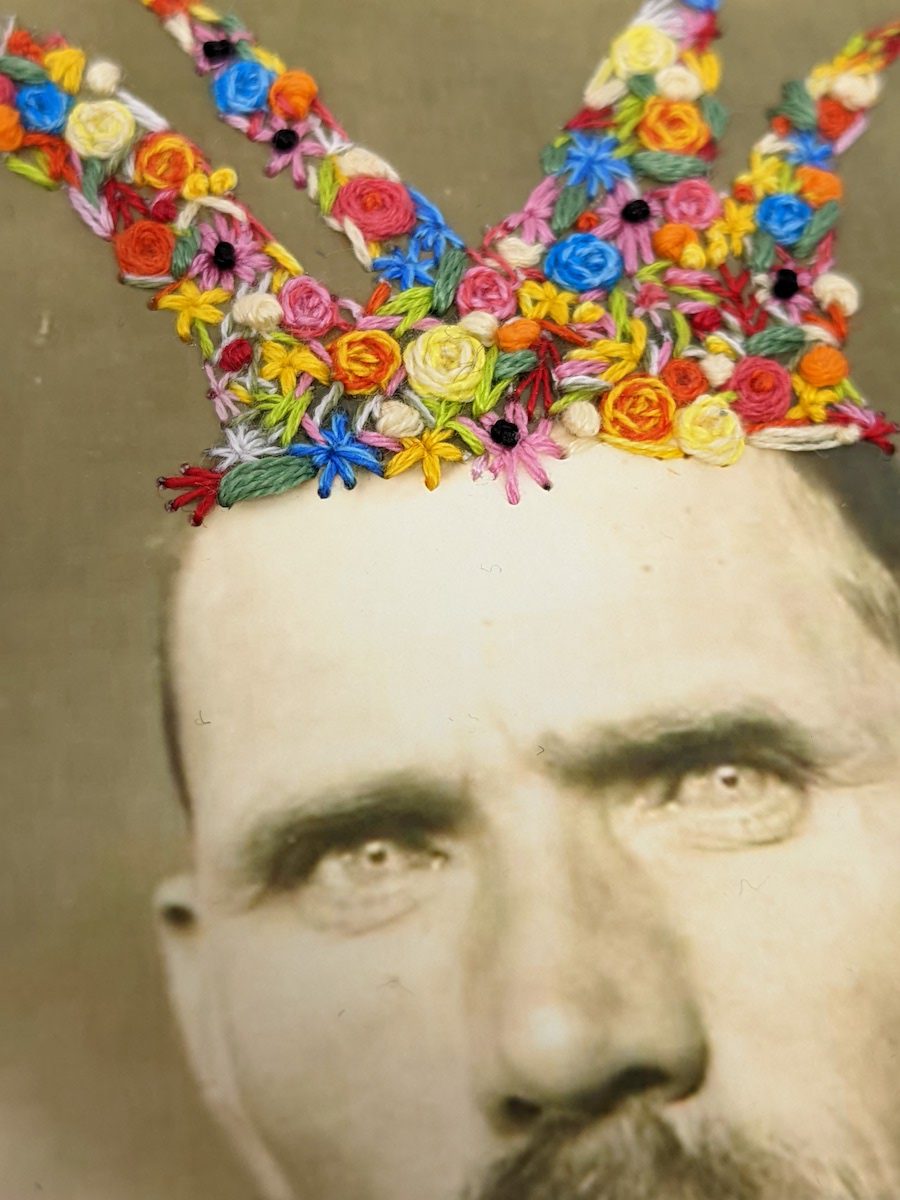

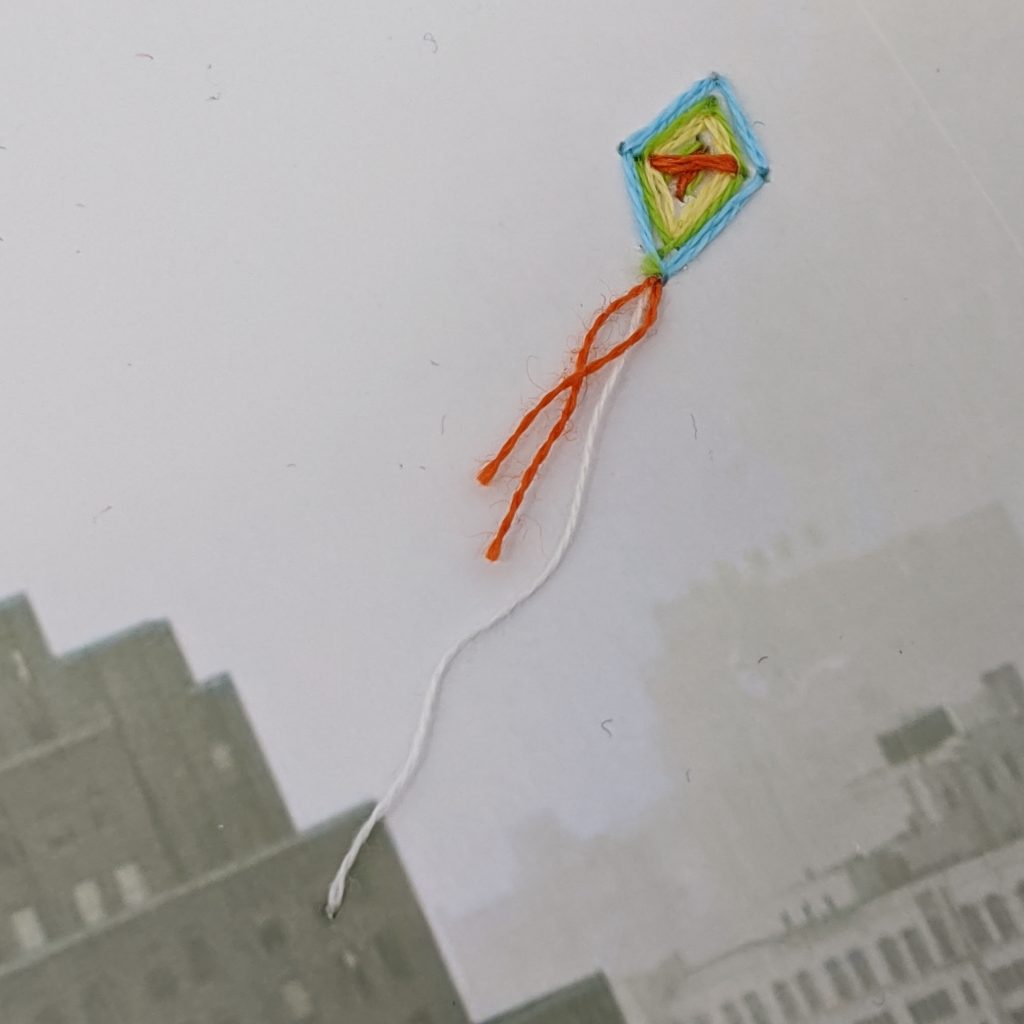

Through Acts of Creation, I was introduced to Mary Beth Edelson’s grotesque goddesses from the 1970s, all wild, unruly figures with snarling mouths, exaggerated limbs, and a refusal to be contained by beauty or decorum. In that space in time days away from giving birth, during which I needed a big pep talk because labor seems scary as hell, I read these collages as, “Fuck you. Look at my warrior vagina. I make life happen, bitch.”

Looking at Edelson’s creations in those last weeks before my due date felt like finding a talisman I didn’t know I needed. These ugly ass goddesses weren’t polite or afraid. They were feral, laughing, ready to split the sky. They reminded me of my body’s strength… that women have done this for centuries. My body, too, was unapologetically strong, strange, and in motion — a reminder that birth is about raw power, a force as old as earth itself. I carried their energy with me into labor, hoping their defiance and vitality could crowd out my fear.

The book spans a wide range of historical perspectives — from ancient cave markings to the use of wet nurses in earlier centuries to the experiences of transgender mothers navigating visibility and acceptance in the art world today. Judah’s profiles of motherhood in art throughout the centuries don’t offer easy blueprints, but they offer something better… proof that a creative life can stretch, bend, and survive the seismic shift of motherhood.

That’s exactly what I needed to read.

The cultural image of the artist as devoted creative monk persists. Door closed, air still, a single shaft of light hitting the desk like divine permission, holy with gravitas and purpose! Instead, Judah documents a different kind of studio — one with kids barging in mid-thought, an empty fridge that takes priority on the to do list, the hum of life bleeding into the work.

It’s not clean. It’s not silent. But it’s still rigorous, and it’s still art.

I also appreciated that Judah didn’t limit her scope to the experiences of mothers alone. She included work grappling with the anxieties of those decided not to have children, those still deciding, and those running out of time to decide.

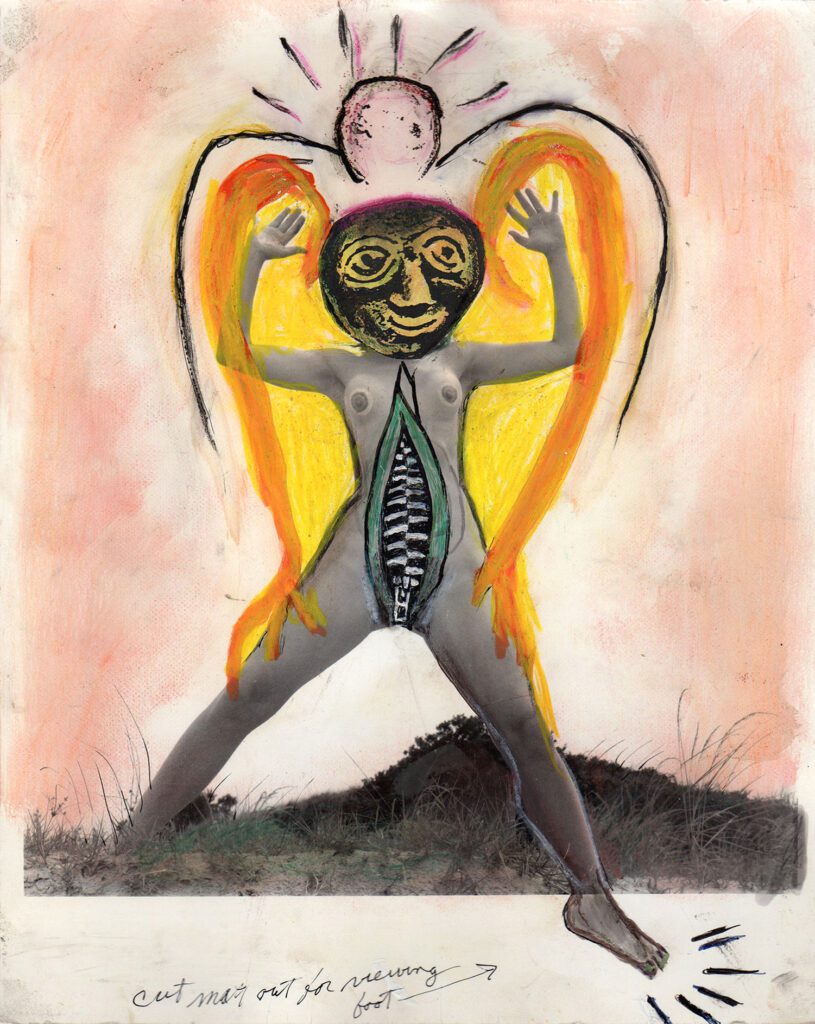

In a recent sculpture by New York-based artist Lea Cetera, Judah writes, “the pink sands of time pour between twinned blown-glass models of the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes. As the title reminds us — You Can’t Have It All (2022). Parenthood hangs in the balance of two timescales. The first is counted in hours — how competing demands of work and self-fulfillment might be balanced against demands of care. The second timescale counts the years of fertility — the dreaded ‘biological clock’ which must be held in consideration against economic variables, romantic status, and career progression.”

Seeing Cetera’s work contextualized alongside stories of artist-mothers made the whole spectrum of choice, circumstance, and longing feel more visible. It is a reminder that the creative life and the reproductive life are often tangled in the same knot of time and expectation.

One of the most provocative ideas to me that Judah explores in the book is the “monstrous child” — a cultural bogeyman used to frighten women away from ambition, as if any child born to an artist-mother will inevitably be neglected, malformed, or damaged by her divided attention. It’s a myth rooted in centuries of suspicion toward women who create for anyone other than their families, a story told to keep the studio door closed.

The “monstrous child” also haunts women who are undecided about having children, fending off thoughts that the wrong choice will devastate them in the future. It dogs those who are childless by circumstance, turning absence into something they must explain or justify without allowing much room for the grief. And it follows women determined to remain child-free, as if they must prove their work or themselves worthy in other ways.

In Acts of Creation, Judah gathers artists who reject or explore all versions of this script, showing instead how children can be collaborators, witnesses, and even catalysts in the creative process. The “monstrous child” is revealed as a projection of society’s own anxieties about women’s autonomy. Children and motherhood can, in fact, be beneficial to the artistic life.

That’s what I am loving most in this book so far… the way Judah frames motherhood not as the antagonist to art, but as a medium that shapes it. Time gets weird — elastic in some places, brittle in others. You learn to work with urgency but also to wait. You get attuned to tiny sensory shifts: the weight of a child’s hand, the fresh dew smell of 4 am, the sounds of a neighbor getting plates down for dinner drifting out of their windows. These experiences make their way into the work, even if it’s slow, and even if they’re removed later.

Acts of Creation makes a case — a real, unapologetic case — for the joy of being a mother, and how that joy can stretch and deepen an artist’s vision. I had longed for Alice with my whole being, and even knowing how much I wanted her, I braced myself mostly for loss… of time, of focus, of money, of the version of myself that had full claim to my days. And yes, it is difficult to juggle it all and I have lost all of those things. My art and writing have taken a back seat for now, the pace slower, the projects fewer.

But oh, what I have gained! I’m discovering that motherhood is primarily an expansion. My world has opened into new textures and layers, my sight sharpened to details I might have otherwise missed, my understanding of human experience complicated and stretched. That shift feels like it’s already reshaping the work I will make next.

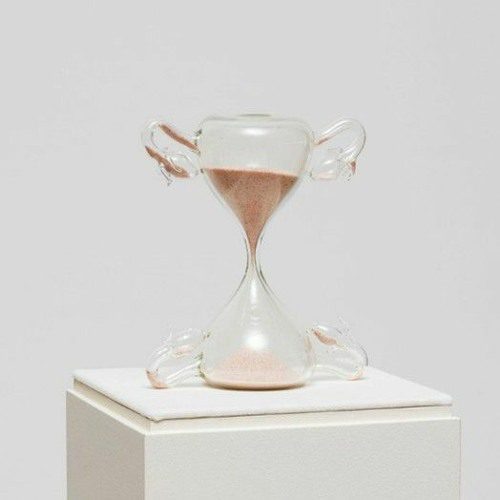

Judah names the invisible… projects abandoned mid-stream. Half-finished canvases stacked in my basement. My novel manuscript still sitting on my desktop unopened for longer than five minutes at a time. The voice memos whispered into a phone in the grocery store parking lot while Alice sleeps in the back. None of these creations “count” in the official sense. But they’re the soil under what will one day be finished pieces.

I know I will finish my work one day because of Alice, not in spite of her.

Motherhood is the same as art making in that it is a practice of holding contradictions without forcing them to fit.

I’m still making my way through Acts of Creation, reading in the same stop-and-start rhythm I make art and write these days. A few pages here, a layer of paint there while baby naps or when I’m on my morning coffee break. I love books like this — ones that make me want to take my time. It’s worth lingering over, letting its ideas filter in between the rest of life. This book reminds me that the art doesn’t have to wait for silence. It can happen right here, with the door open, the air thick with noise, the work humming along in the midst of it all.

The pendulum swinging between concealment and celebration of artist-mothers during the 20th century still feels relevant today. Some felt they had to hide their children entirely to be taken seriously, tucking away any sign of domestic life so their work wouldn’t be dismissed as “mere” mother’s art. Others found moments when motherhood itself was celebrated, framed as proof of depth or authenticity. Reading these histories, I felt the echo of that divide — the defensiveness that can simmer between mothers and non-mothers in creative spaces, each group wary of how the other’s choices might be judged or romanticized. It’s a tension worth naming, if only so we can imagine something less polarized.

The experience of the mother-artist — with its complexity, interruptions, and unexpected expansions — is robust and alive with possibility. It deserves to be looked at closely, told in full, and explored again and again, not as an exception to the artist’s life but as a vital form of it.

***