The objects we use on a daily basis play a big role in our cultural story and memory. As writers, we know the importance of objects in terms of symbolism—and ensuring we are, when writing fiction at least, placing historically accurate objects into settings, character descriptions, and dialogue.

Your Civil War heroine with an iPhone is no bueno, bud.

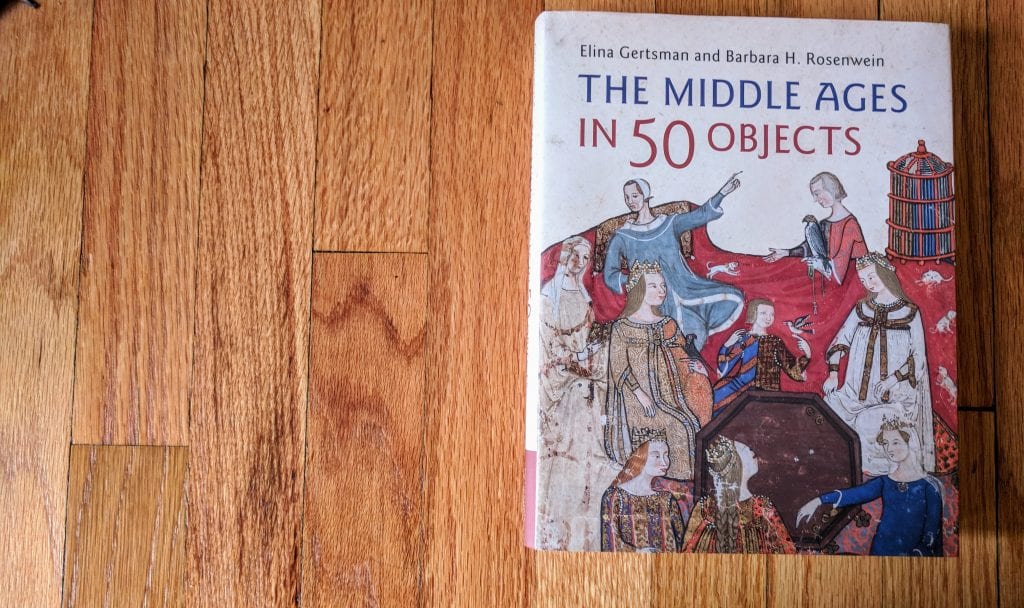

That’s why tomes like “The Middle Ages In 50 Objects” (Cambridge University Press, 2018) are so helpful to writers doing research for a novel or screenplay in this time period. “50 Objects” features beautiful images of objects from the Cleveland Museum of Art paired with an essay that digs into its visual and cultural significance within the wider context of how the object was made or used.

The book is divided into four topic areas (The Holy and the Faithful; The Sinful and the Spectral; Daily Life and its Fictions; and Death and Its Aftermath) and loaded with fresh historical insights provided by the scholars Elina Gertsman (professor of Medieval Art at Case Western Reserve University) and Barbara H. Rosenwein (a medievalist who specializes in the history of emotions).

And though it was written in part to progress academic conversations about the Middle Ages—and recently made the High Brow/Brilliant end of New York Magazine’s approval matrix—this book is a visual and intellectual goldmine for arm chair art history lovers. <raises hand> Reading this book was like getting an answer key to some incredible works of art; like sitting in on a university lecture from the comfort of my aforementioned arm chair.

Example: Object 22’s painting of the Madonna and Eve on wood panel features inverted letters signifying the way Mary supposedly reversed Eve’s original sin; Eve’s sexuality is underscored by the Tree of Knowledge growing between her legs. (Which, if ever there was an ideal place for a tree of knowledge to grow, I’d say it’s there… She wouldn’t even have to stand up to pick out a new book to read from its branches! #teameve)

I had the pleasure of asking Elina and Barbara a few questions about the process of writing their new book, why they made the curatorial decisions they did, what objects in the book were most interesting to study, and more. Read their thoughtful answers below, then get your own copy of “The Middle Ages In 50 Objects” here!

The hard cover is coffee table chic.

***

Why are objects worth studying in order to understand the past?

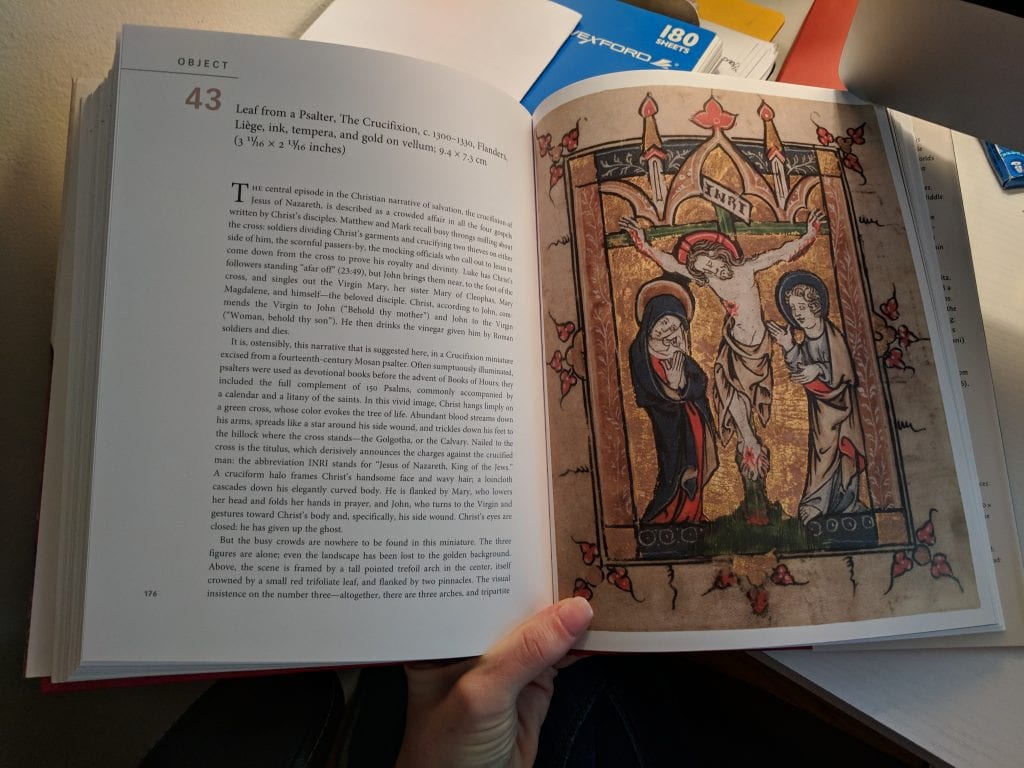

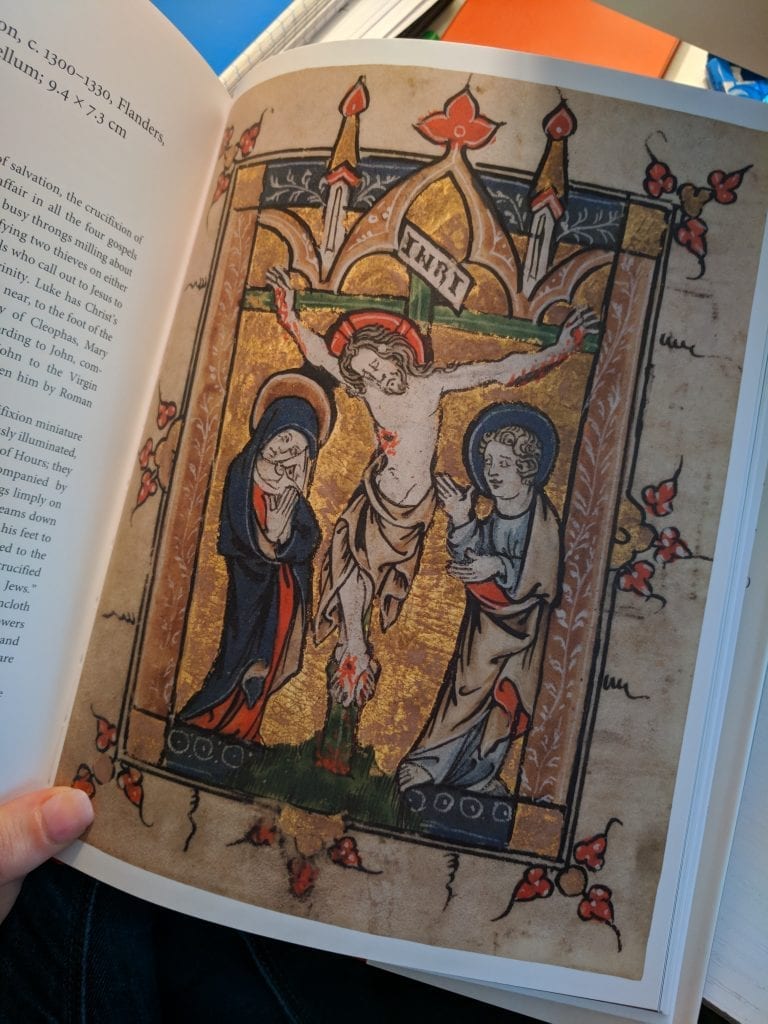

Objects are not just things “out there” but agents of history in every way. They are created for reasons ranging from utterly practical to outrageously frivolous—but always in ways that are particular to certain people and places at particular times. As they come into being and use, they carve out their own meanings and interact with other objects—and people. Consider the scene of the Crucifixion (Object 43): the bottom of the Cross depicted there has been touched by pious fingers and lips so many times that the paint and ink are smudged.

The Middle Ages was a culture of the senses. Think of the incense perfuming the air in places of worship (churches and mosques alike), the music of liturgy and entertainment, the visions of color and light afforded by manuscript illuminations, the taste of the Eucharist melting in the mouth, and the invitation to touch offered by ivory and alabaster. Considering objects in all their materiality opens a royal path to this rich and little-known culture of the past.

How did you narrow it down to just 50 objects?

We wanted to produce a book that would be both comprehensive and yet not overwhelming. We knew that each object we chose would be worthy of many pages of explanation, but we decided to limit ourselves there as well. The number 50 seemed a good solution: enough to cover several entangled cultures that had to be considered together in order to illuminate each one.

How would you describe working on this book? Was it a joyful experience?

Joy is the right word. The book almost wrote itself once we had decided on the themes and the objects that belonged to them. We generally worked in relay. Elina lit the torch, as it were, by focusing on the objects, teasing out the network of associations they triggered, visual discourses they tapped into, and the ways in which they were viewed in the past. Then it was Barbara’s turn to consider the larger context, wrapping each object in the intricate web of events, patrons, social needs, and religious uses that explained its creation and importance.

Why did you decide to balance the representation of objects used or cherished by the elites and those used or cherished by the non-elites?

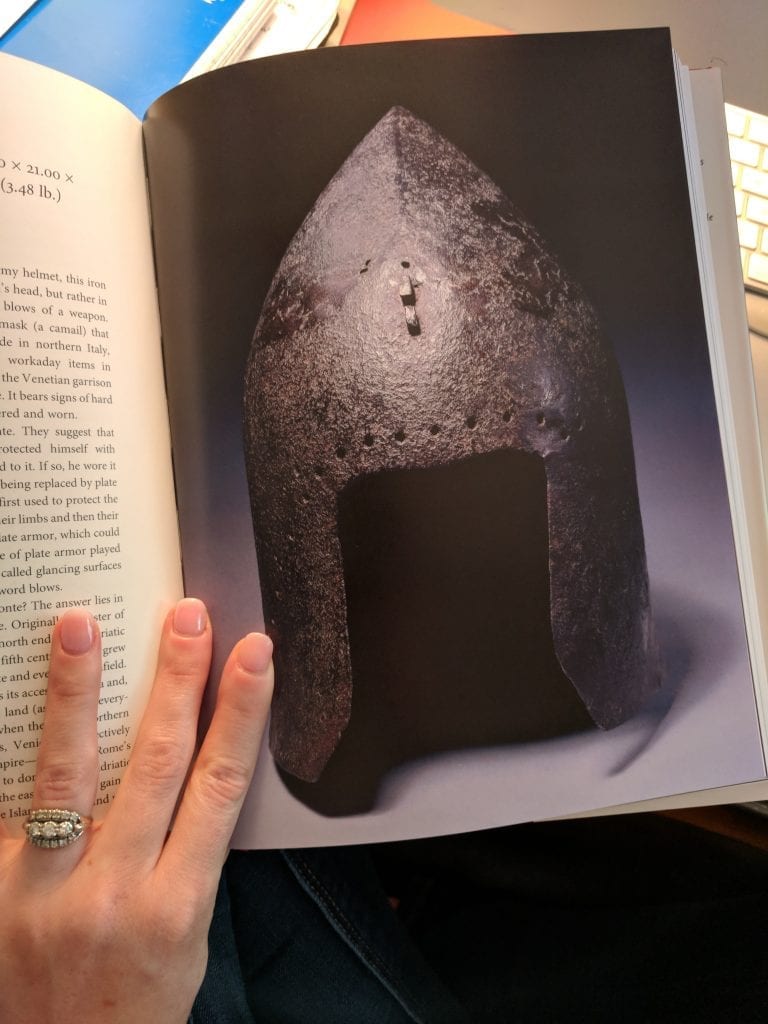

There is no denying that medievalists have on-hand more material objects from the elites than from the non-elites. Patrons of the arts—both individuals and institutions—were normally wealthy, and we today prize the results of their largesse and taste—the astonishing delicacy of Books of Hours, emotionally evocative images of Saint John softly resting his head on Christ’s shoulder, or elegant tombstones made to mark the burial of pious Muslims. But it is also important to see and understand the material lives of others less well-to-do, for they represent the majority of people in every period. When we view an iron barbute (Object 37), we are brought into the world of the soldier.

Its pits and dents remind us of the everyday dangers and hardships suffered by men in the Venetian army garrison at Negroponte. Negroponte? What was Venice doing there, 1,200 miles from home? The barbute thrusts us into the thick of historical events, as Venice takes over an island that had long belonged to Byzantium. Surely, we must cherish it almost as much as the man whose life it protected.

I really enjoyed the way you divided the contents into four topic sections. Was it difficult to organize? What was your thinking behind dividing them in this way?

We didn’t want to do the West first, then the Islamic world, then Byzantium, or anything of that sort because those cultures were too intertwined to be conceptualized in that way. Nor did we want to divide the book by chronology, as if it were a textbook. We chose, rather, to work with themes that cut across the whole period and united all of the cultures.

Did any of the 50 objects surprise you or is there an object in the book you particularly liked learning about?

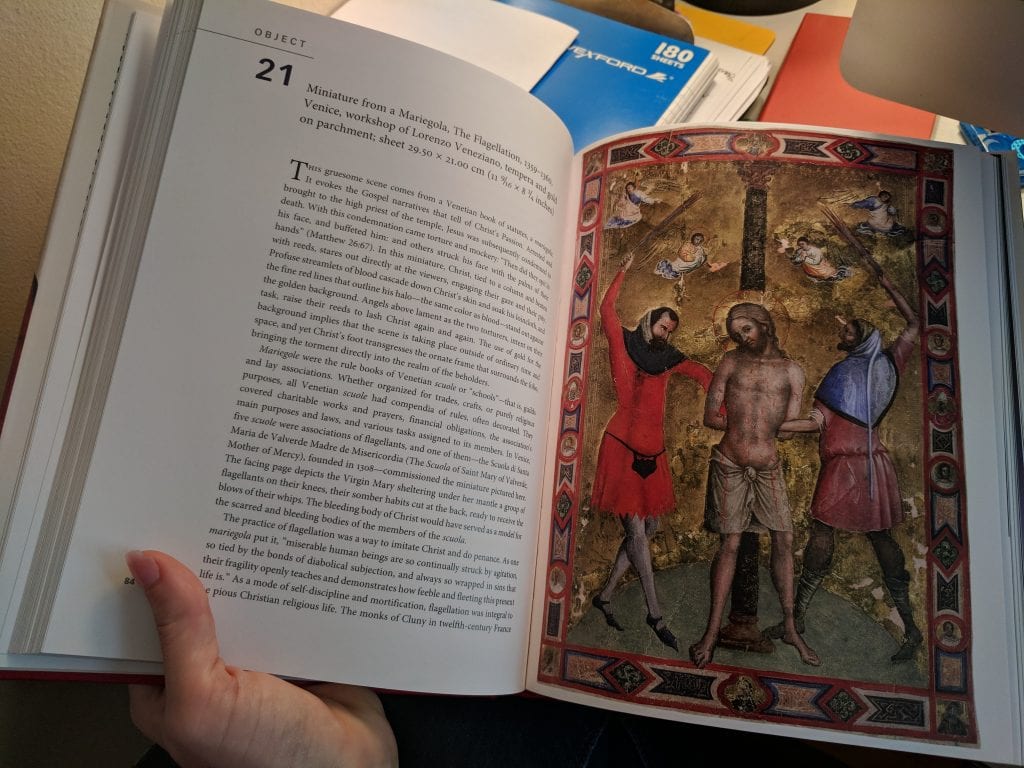

All of the objects turned out to have surprising twists and turns. But we especially enjoyed working on objects that opened up many different paths to explore. An example is the miniature from a Mariegola (Object 21), which required us to research Venetian guilds, anti-Jewish stereotypes, ideals of poverty, and the realities of untold wealth.

Can learning about objects from the Middle Ages help us better understand the objects of contemporary visual culture?

There is no question that sensitizing ourselves to the objects that mattered in the Middle Ages helps us understand our own. But beyond that, some of the same themes and uses have distant echoes today. This goes beyond obvious similarities, as for example the persisting image of the Crucifix. Consider depictions of Death as a skeleton (see Object 50) or contemporary gestures of prayer, which derive from the medieval practice (see the hands of the Virgin in Object 43).

If you could pick one or two objects from contemporary culture that you think future historians would find important, what would they be?

Barbara: I’d choose the Apple Watch, which is a fashion accessory, a practical conveyer of time and information, and a good symbol of our desire to be constantly in touch without touching.

Elina: I’d choose a pair of boots: shoes are always a powerful symbol of presence and loss, and the last century or so has been deeply fraught. Shoes are intimately tied to memory, often terribly so: the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum displays thousands of shoes, taken from the prisoners at the Majdanek concentration camp. Just two months ago, countless pairs of shoes were placed in front of the Capitolio in Puerto Rico, to mark the absence of men and women lost in Hurricane Mari and unaccounted for in the official death toll.

What has been inspiring you lately? Any books, music, podcasts, movies to recommend?

Barbara: In a small 12th-century church in Saint-Dyé, France, I heard an incredible concert that combined ancient instruments and songs with compositions by a living composer. The music worked together seamlessly, making the past present and the present past ways I could not have imagined. It was truly inspiring.

Elina: I am reading Paul Auster’s splendid “4321”—complex, sensitive, always stirring, dark at times, but somehow always jubilant. I’d recommend it without reservations.

If you could invite three people, living or dead, to a dinner party, who would they be and why?

Barbara: This is tough. I’d love to have a good dinner conversation with many people. But I guess I can narrow it down to one party in which the guests might compare notes and (let’s hope) learn from one another. I’d invite Xanthippe, Socrates’ wife, who was billed as a nasty shrew by Xenophon; Christine de Pizan, a late medieval feminist who supported herself and her family by writing witty books for wealthy patrons; and lastly Catherine Dickens, best known as the unhappy wife of Charles Dickens. My first question to them would be: What place should women have in society, and what attitudes, institutions, etc. would be required to get them there? And my second question: If you could choose a different time and place to live in, what would it be? If I dared I might pose a third: What do you think of the LGBTQIA movement, and what do you think it portends for gender relations in the future?

Elina: I’d invite Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th-century German visionary; Voltaire, an 18th-century French Enlightenment philosopher; and Andrei Voznesensky, an extraordinary Soviet/Russian poet, who died just a few years ago. I’d love to hear them talk about poetry, politics, and everything in between.

One thought to “10 Questions: Authors and historians Elina Gertsman and Barbara H. Rosenwein”