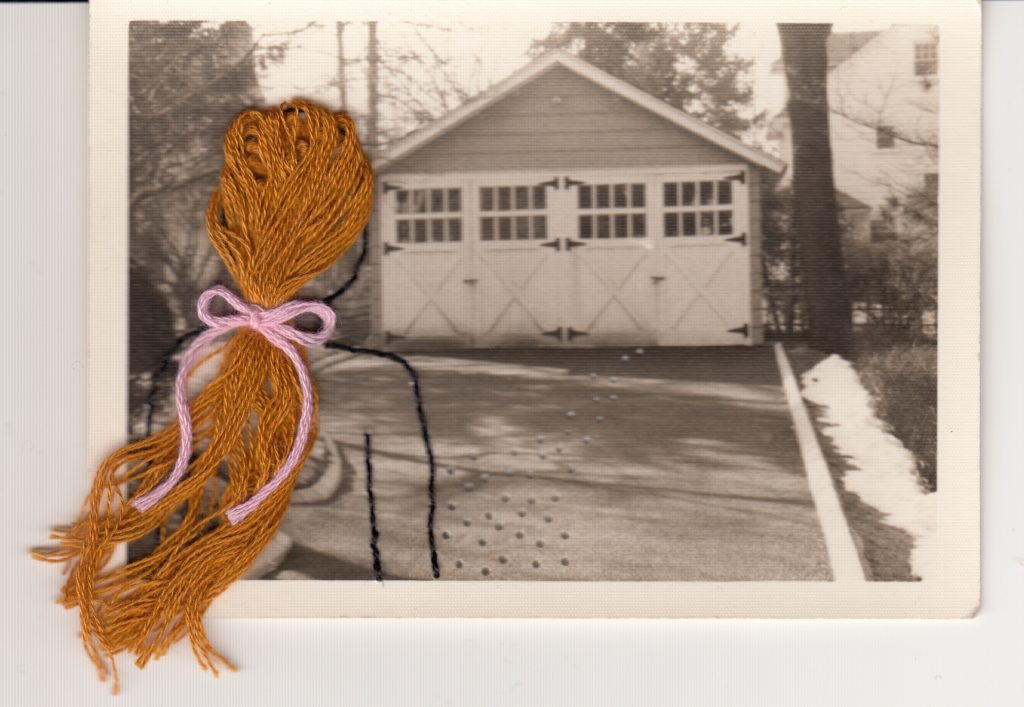

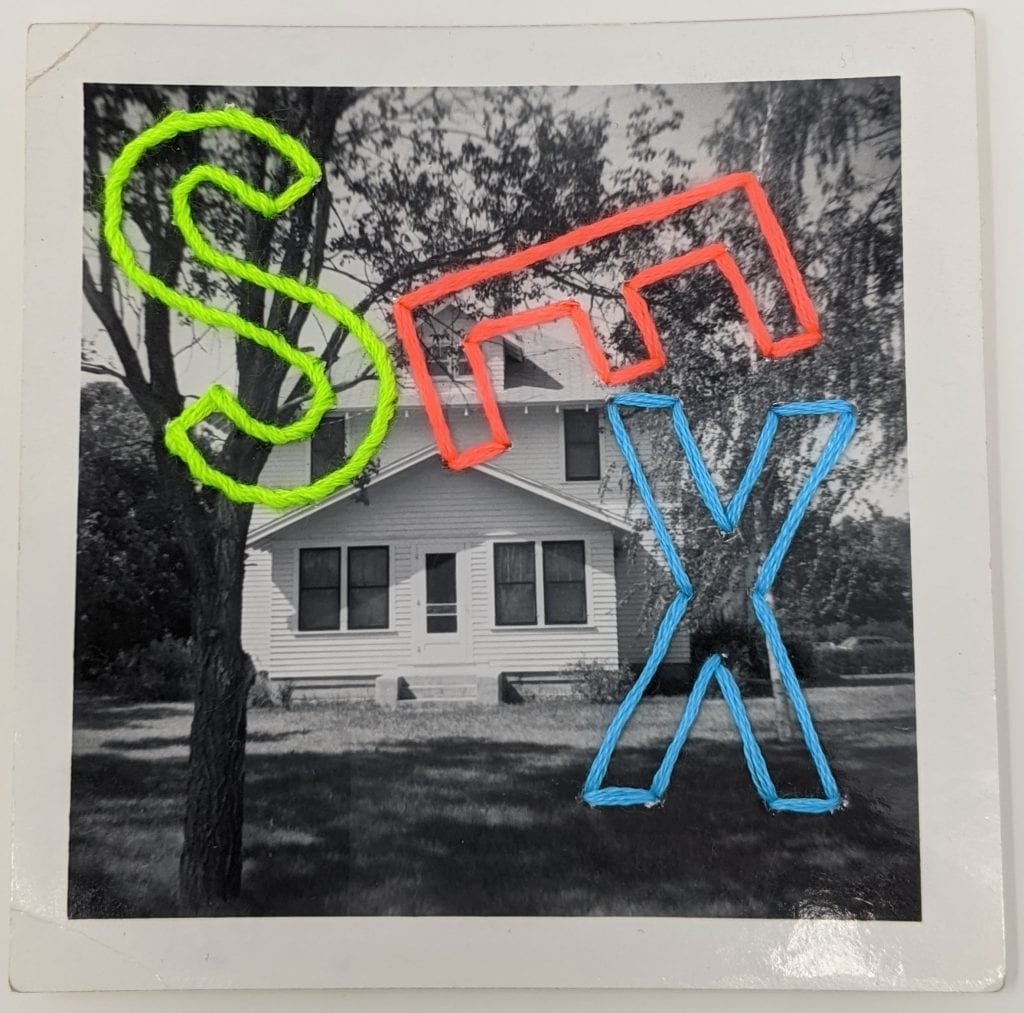

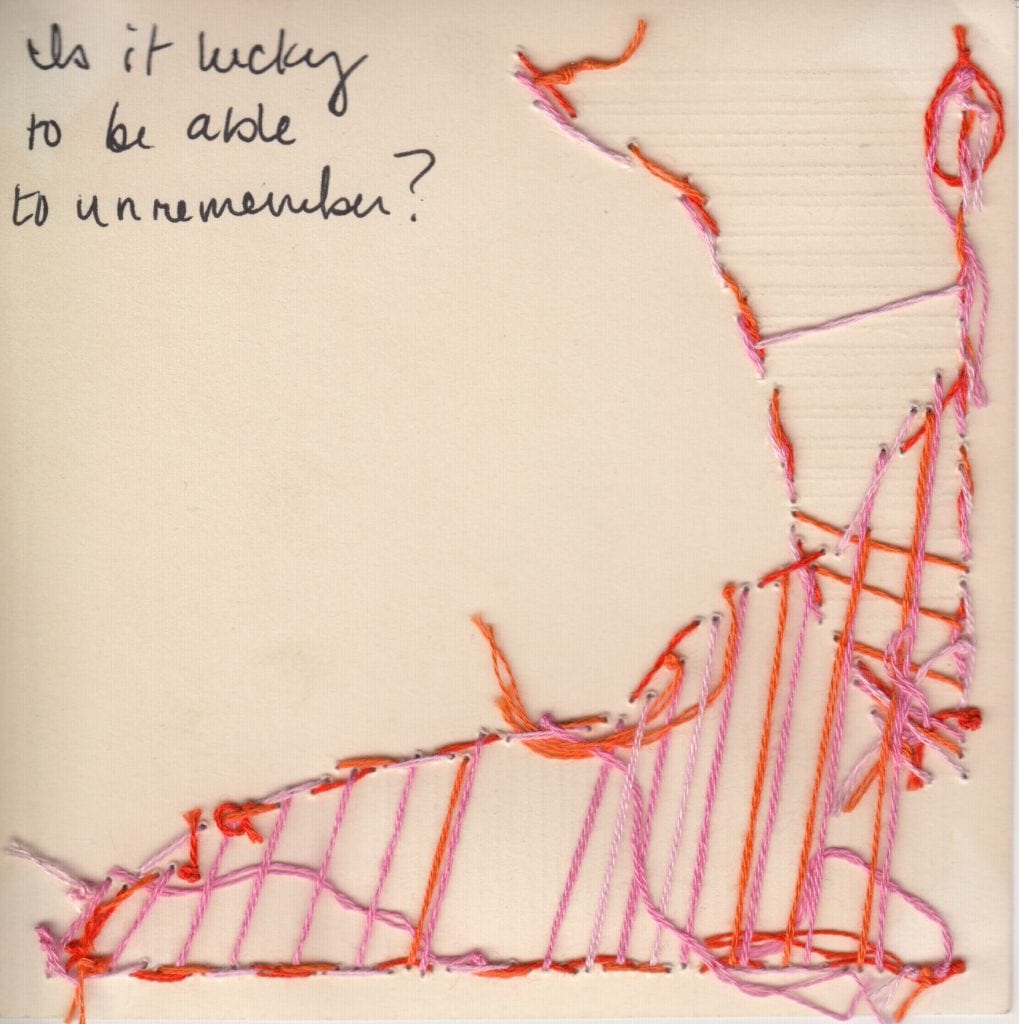

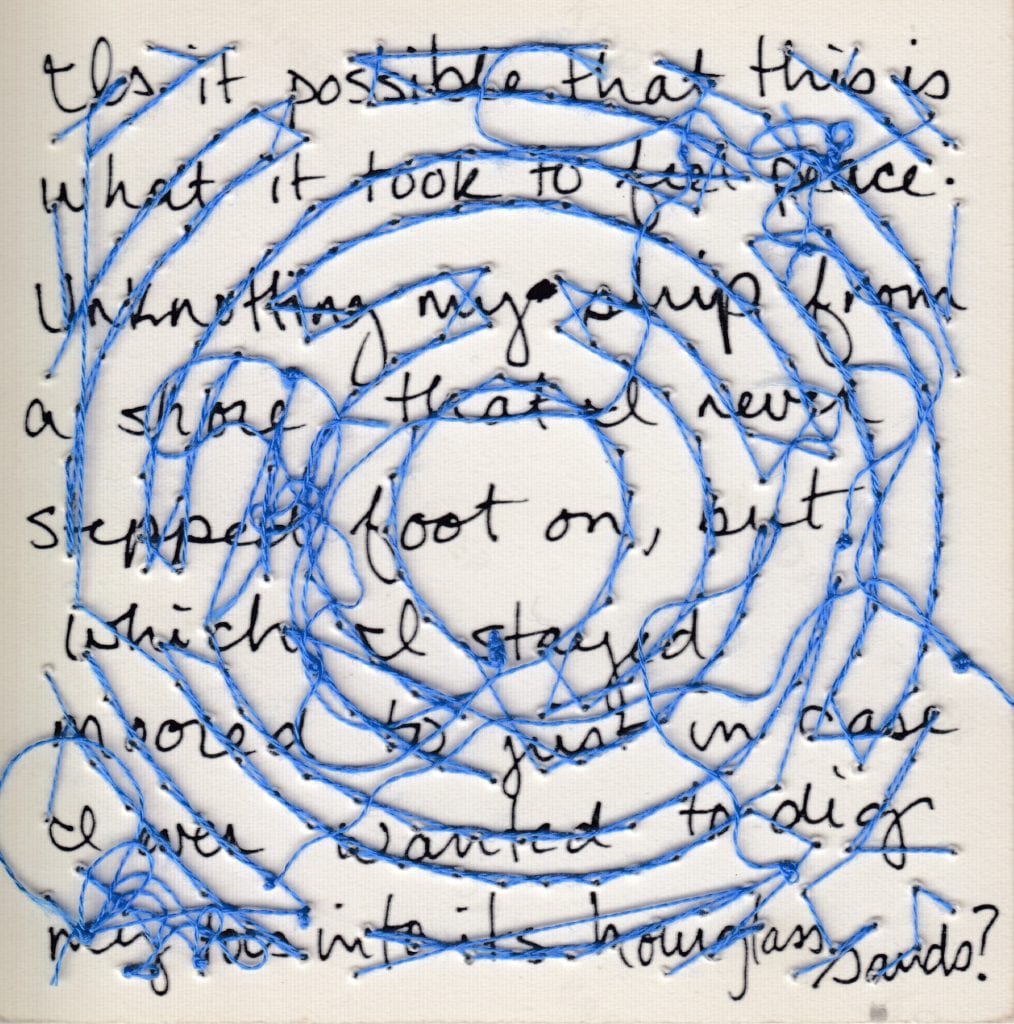

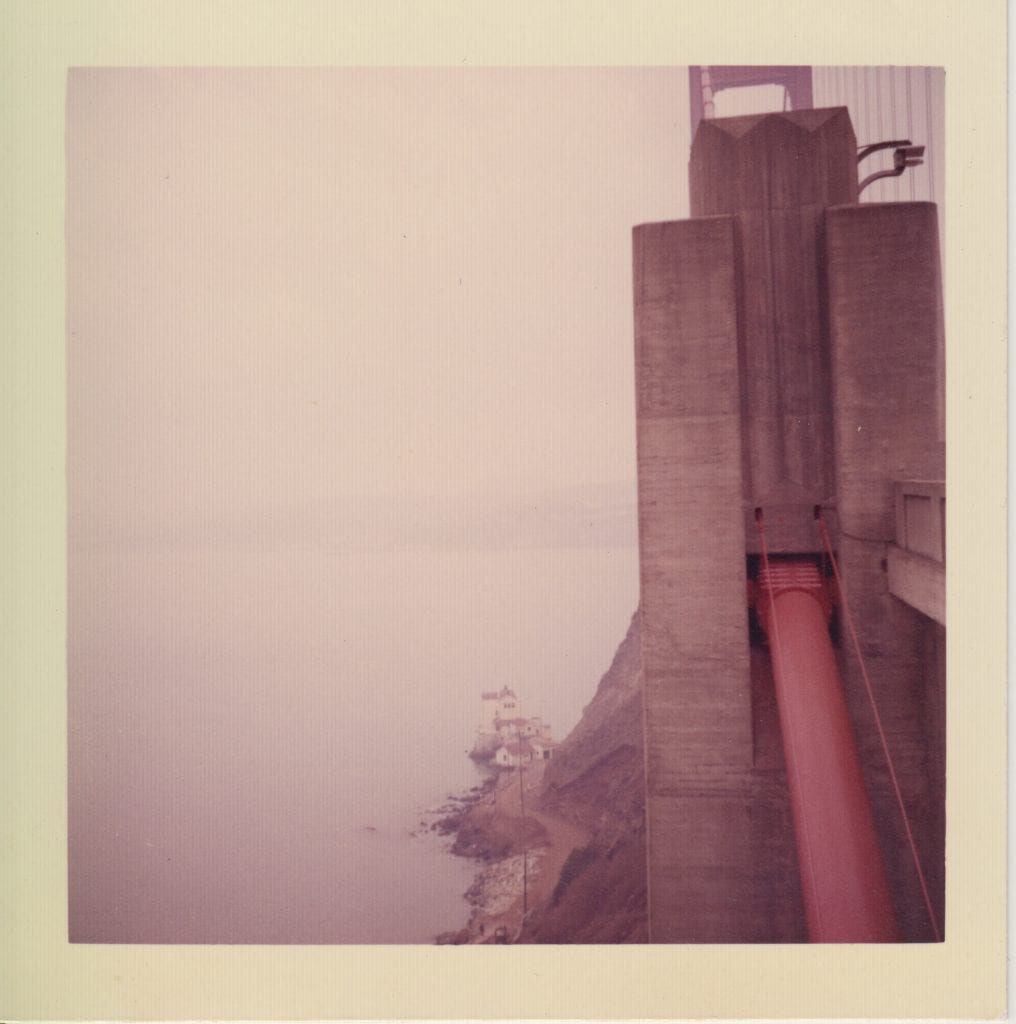

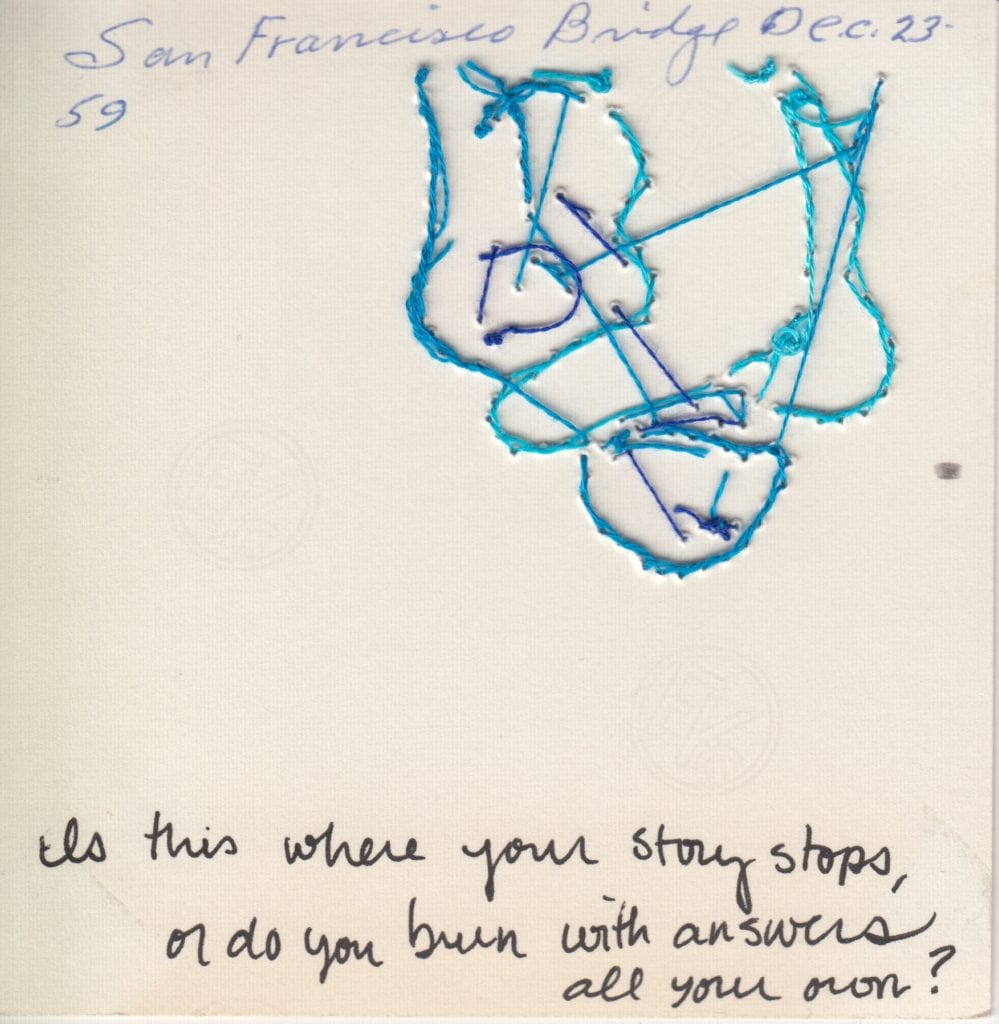

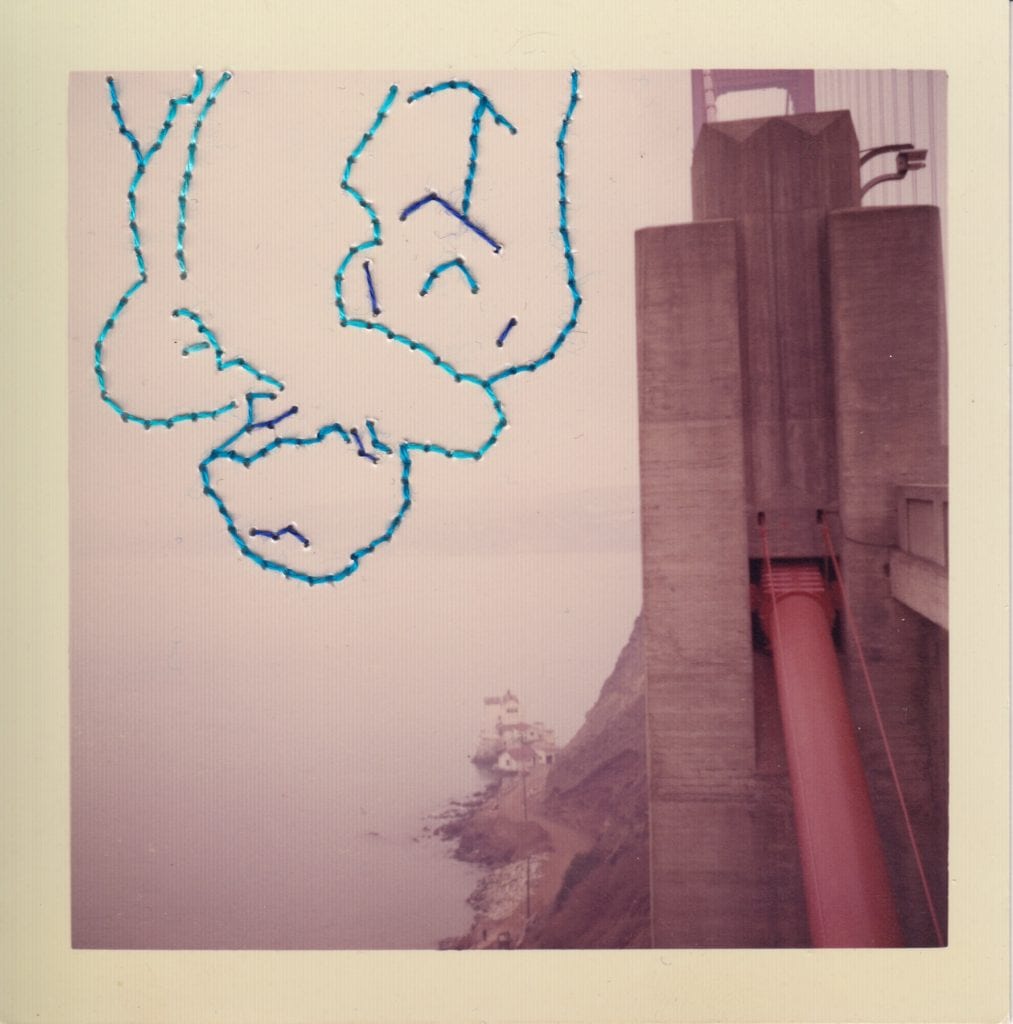

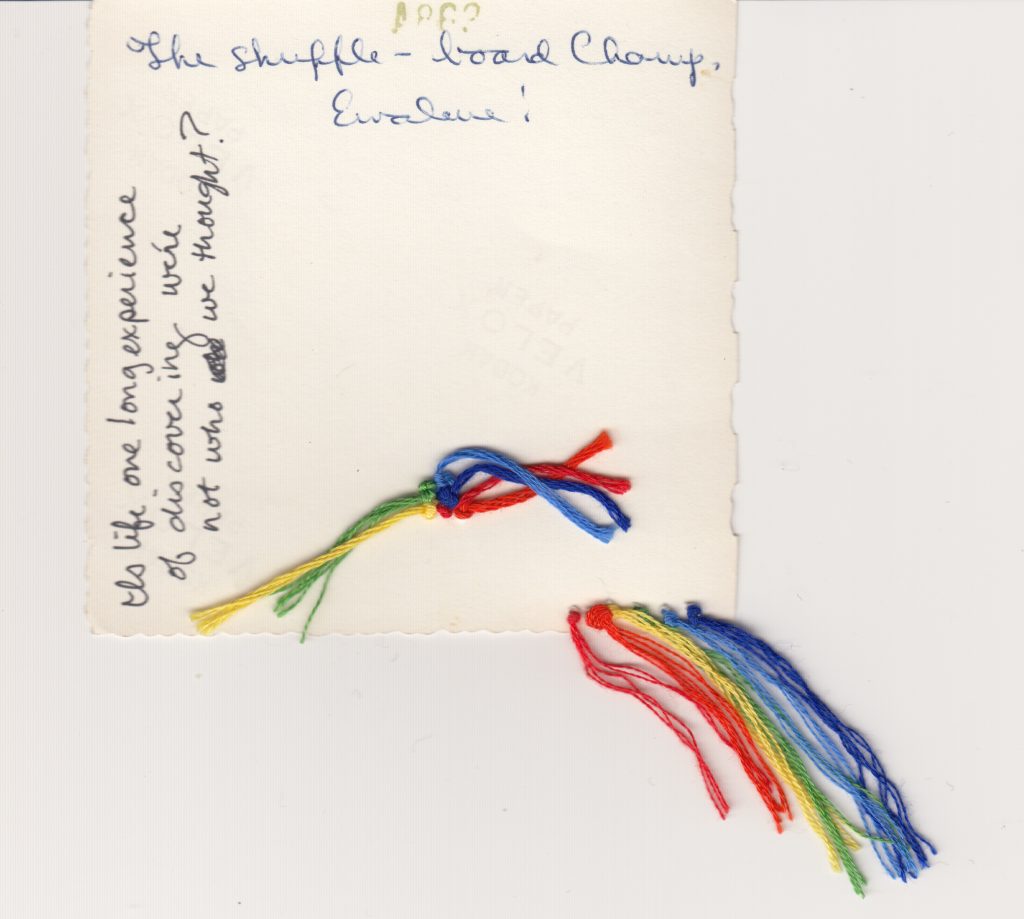

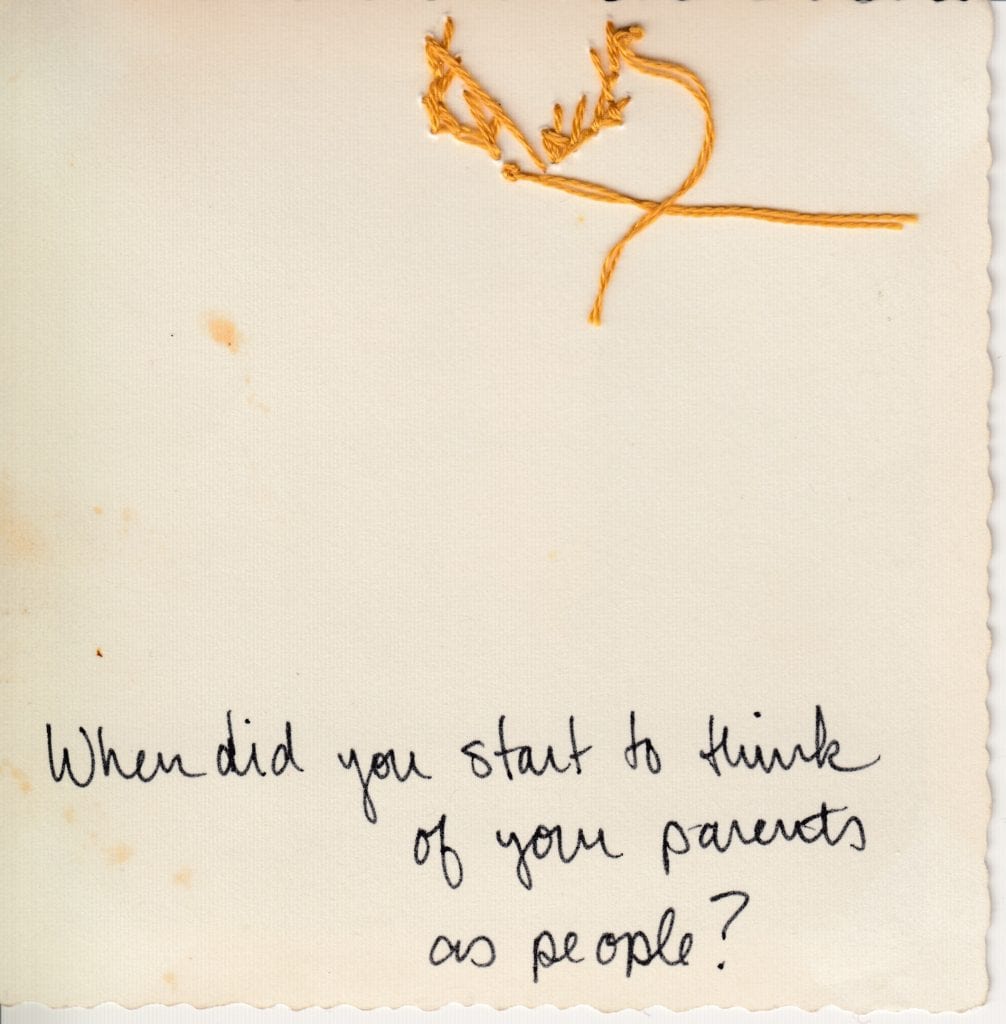

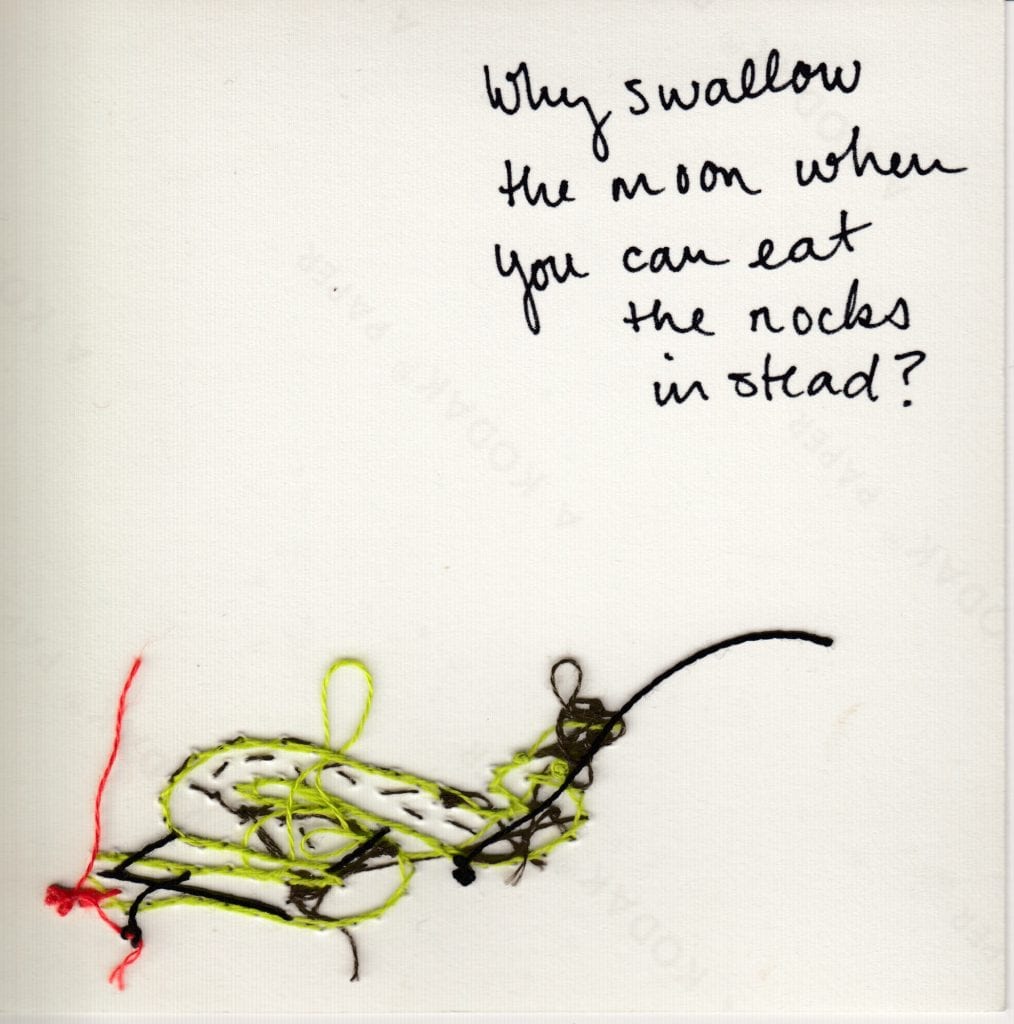

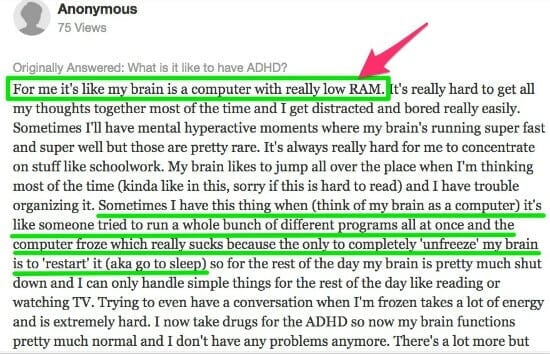

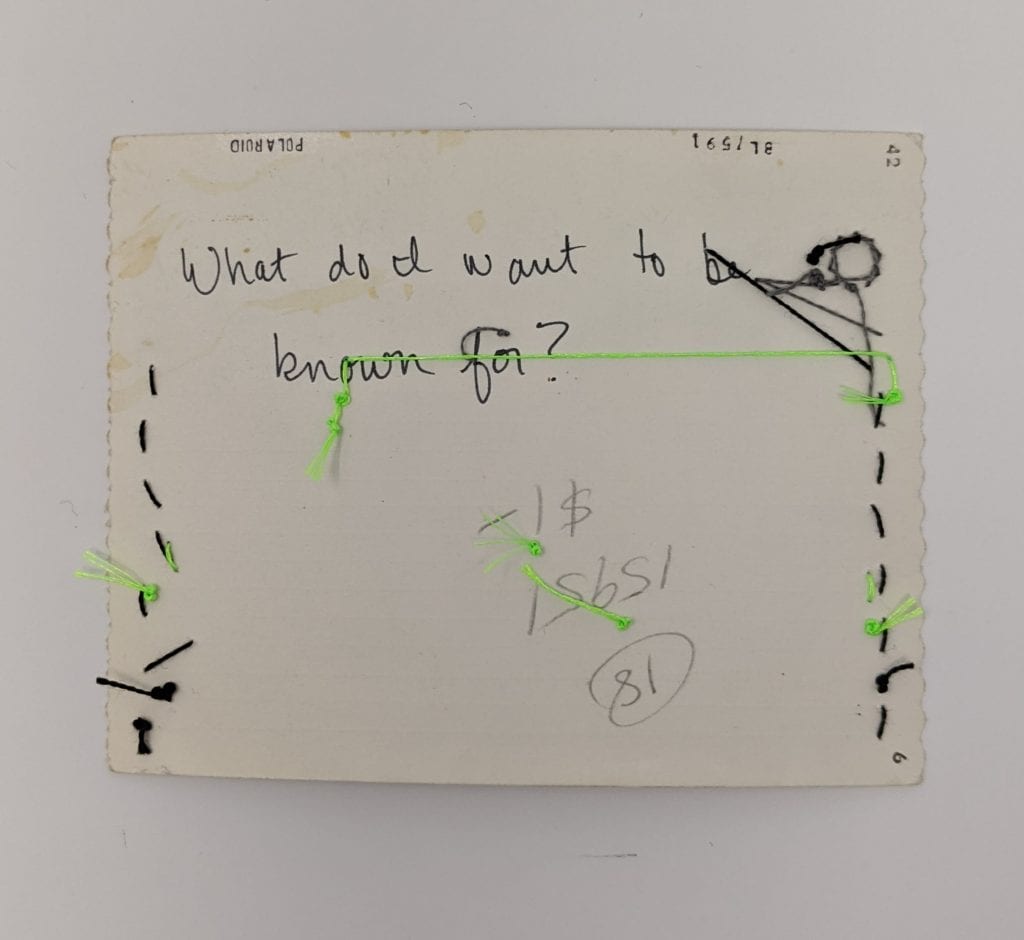

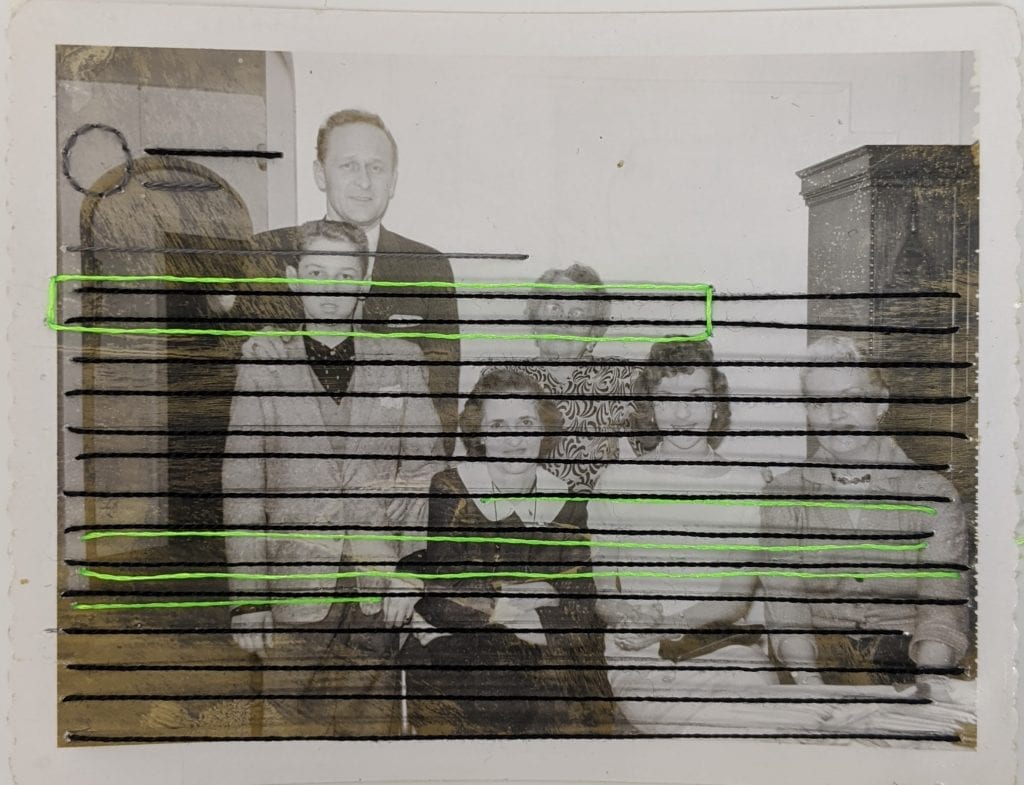

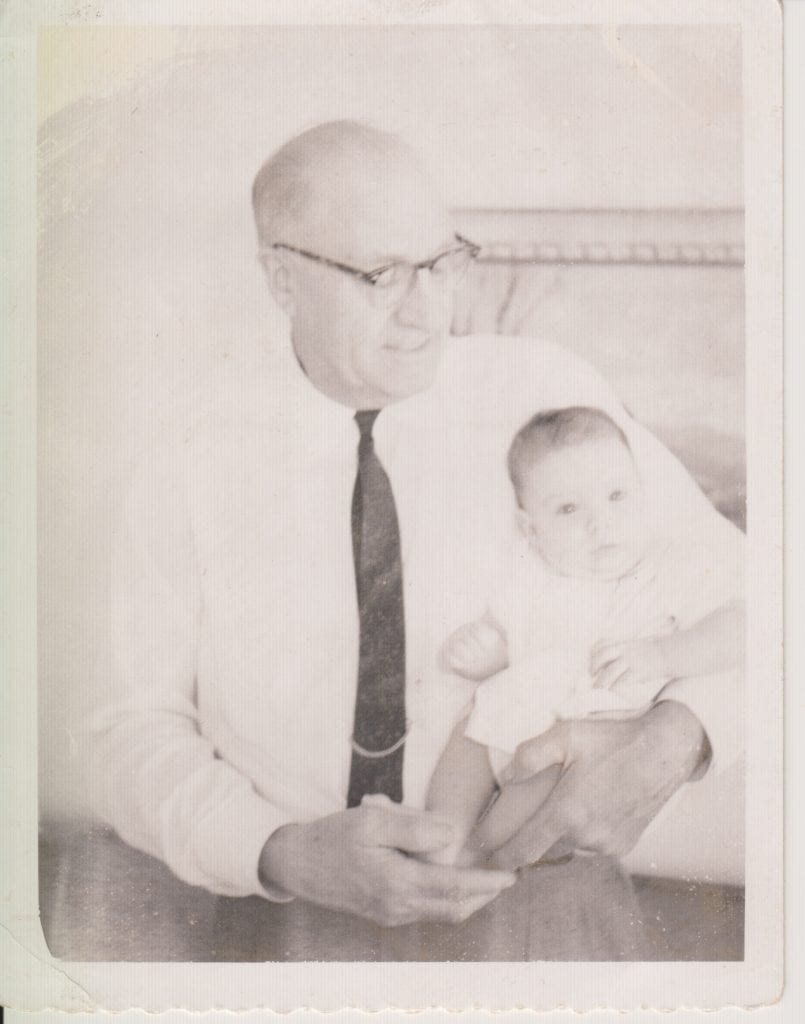

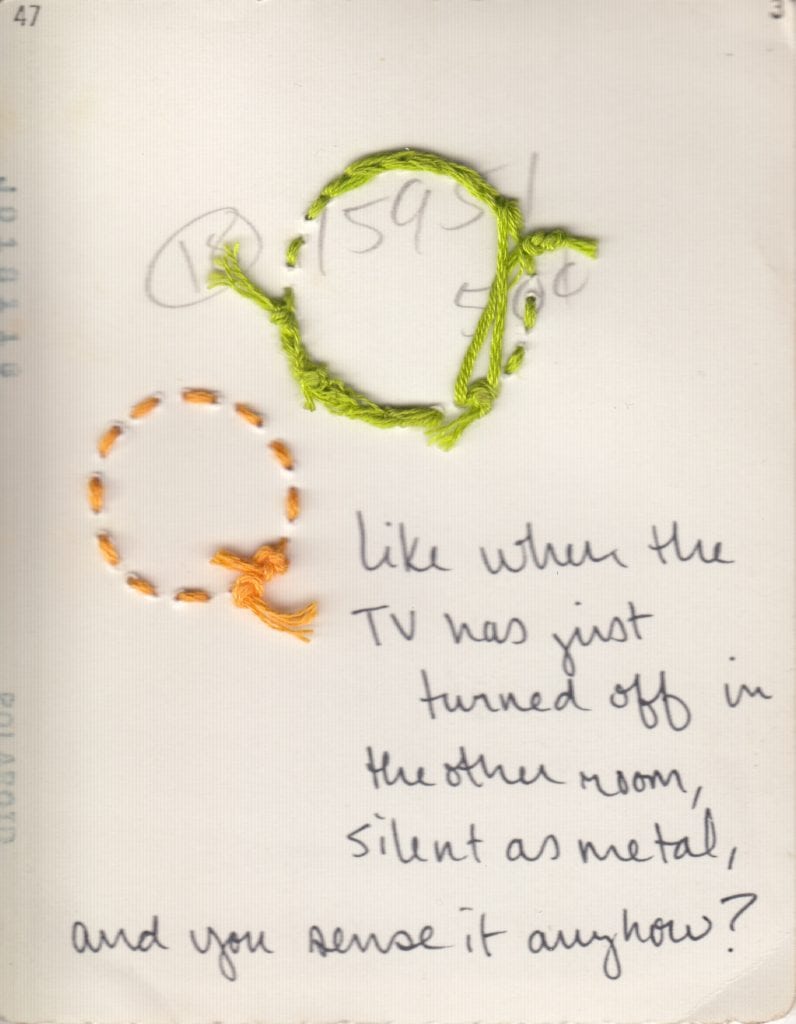

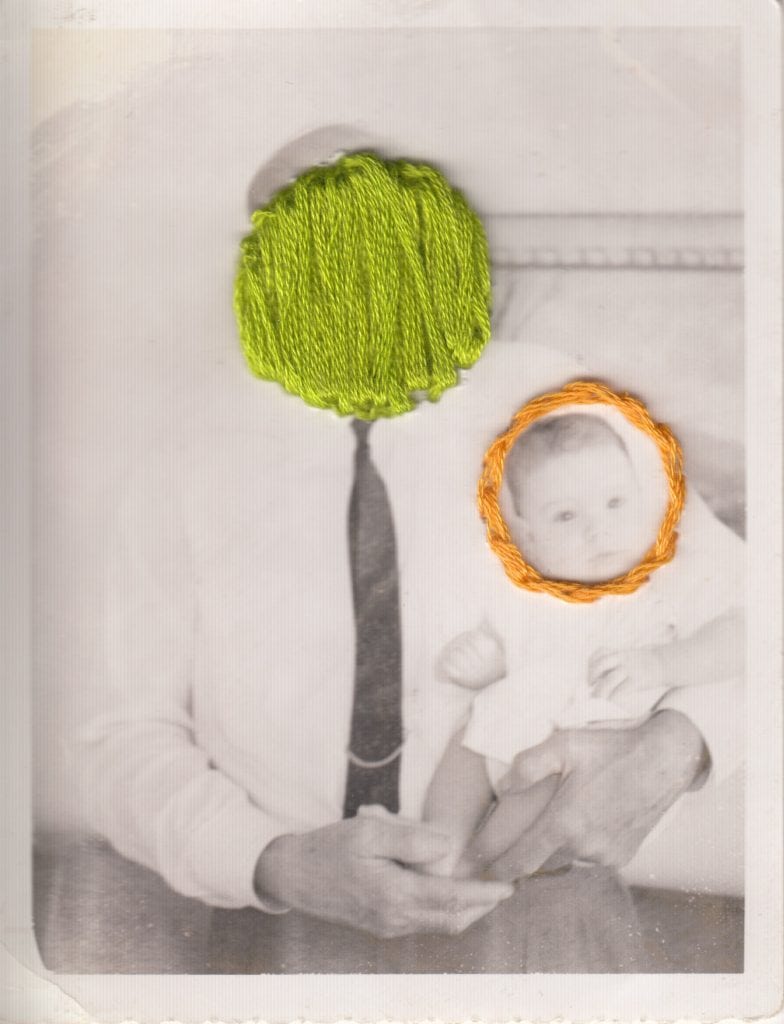

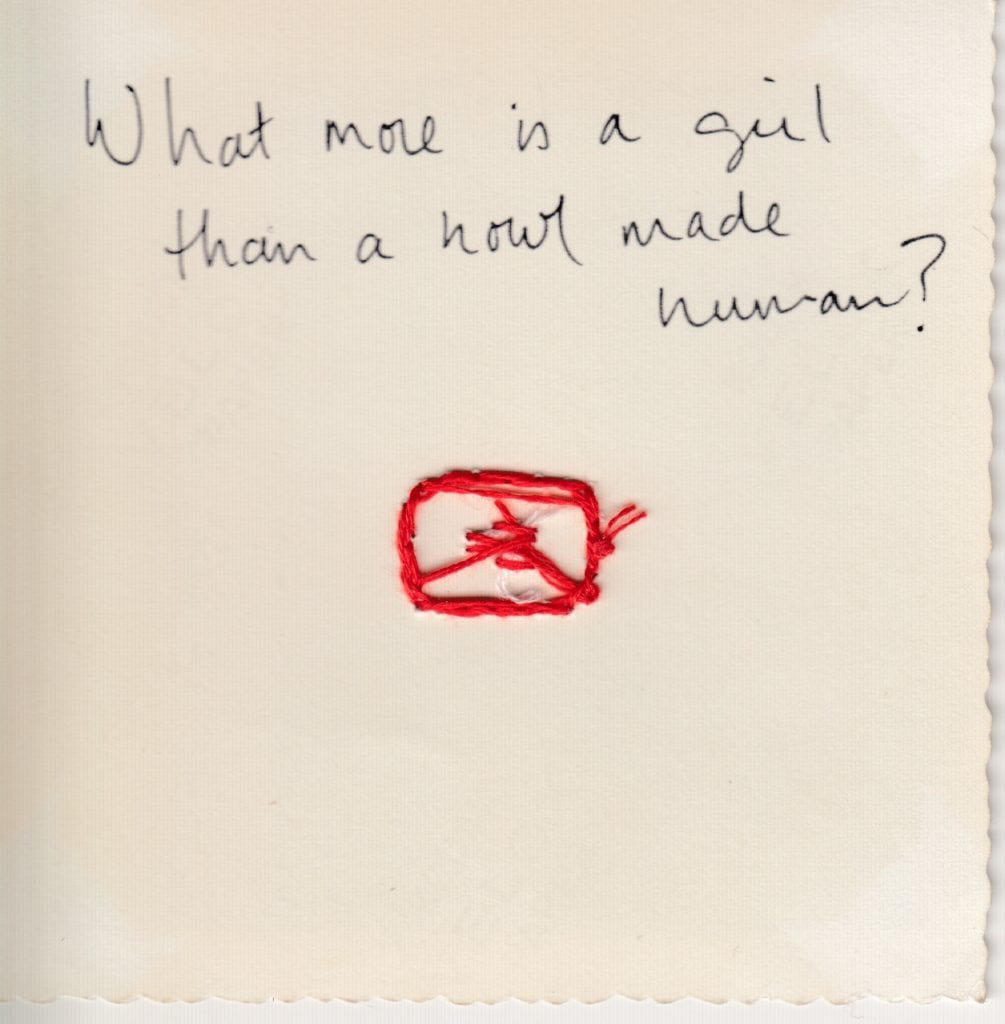

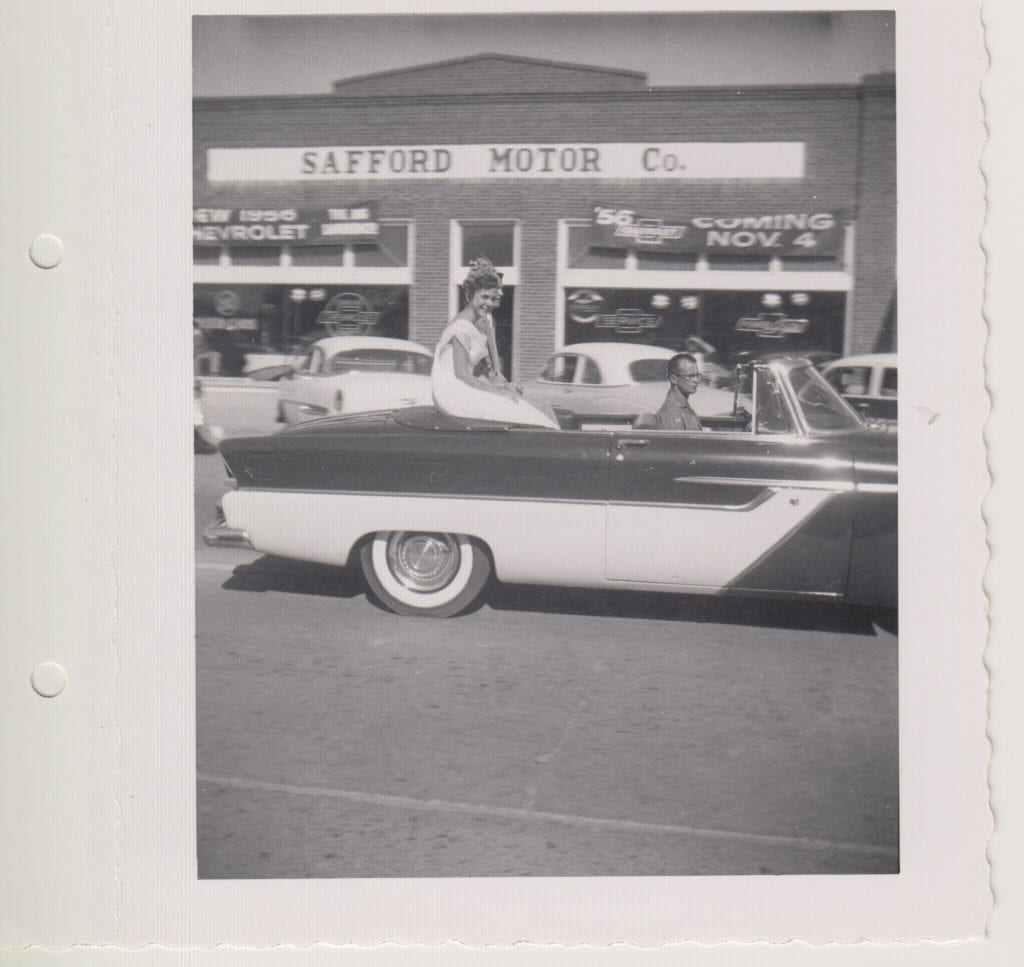

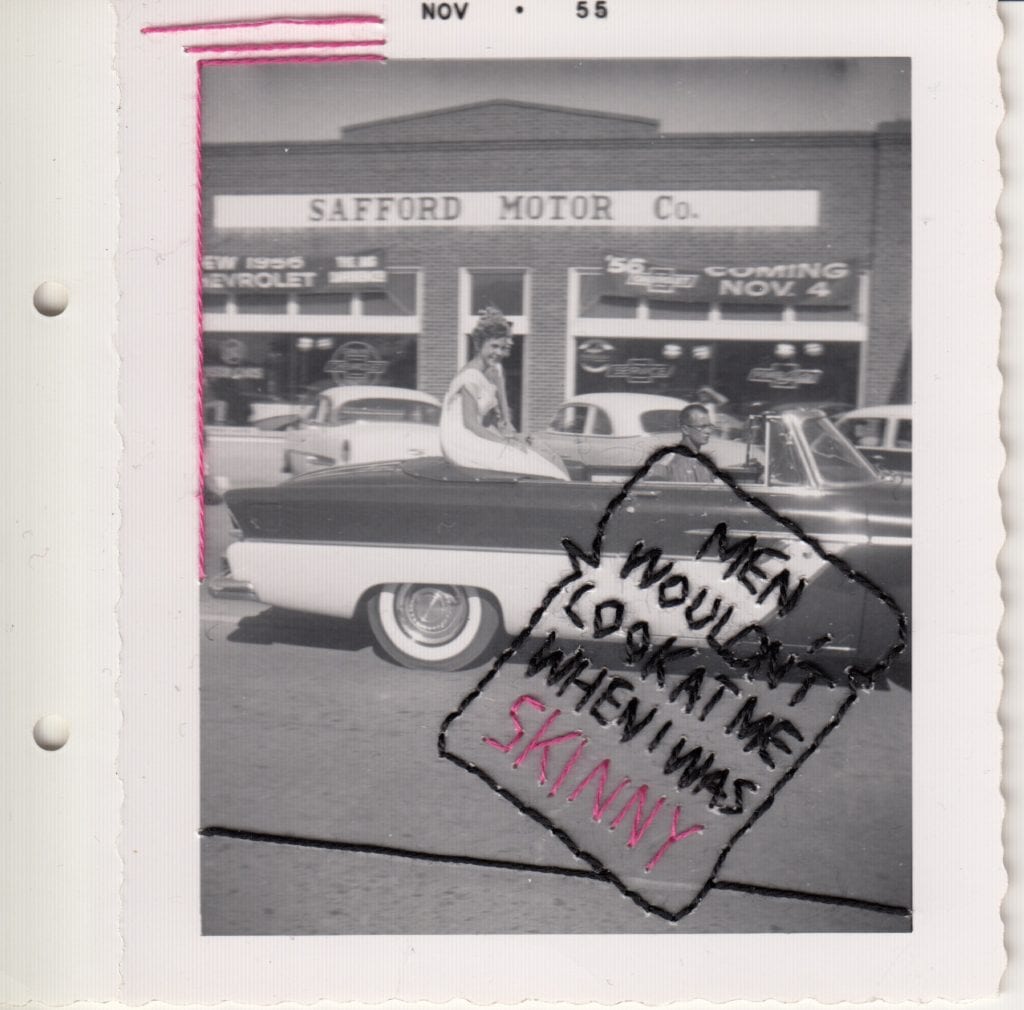

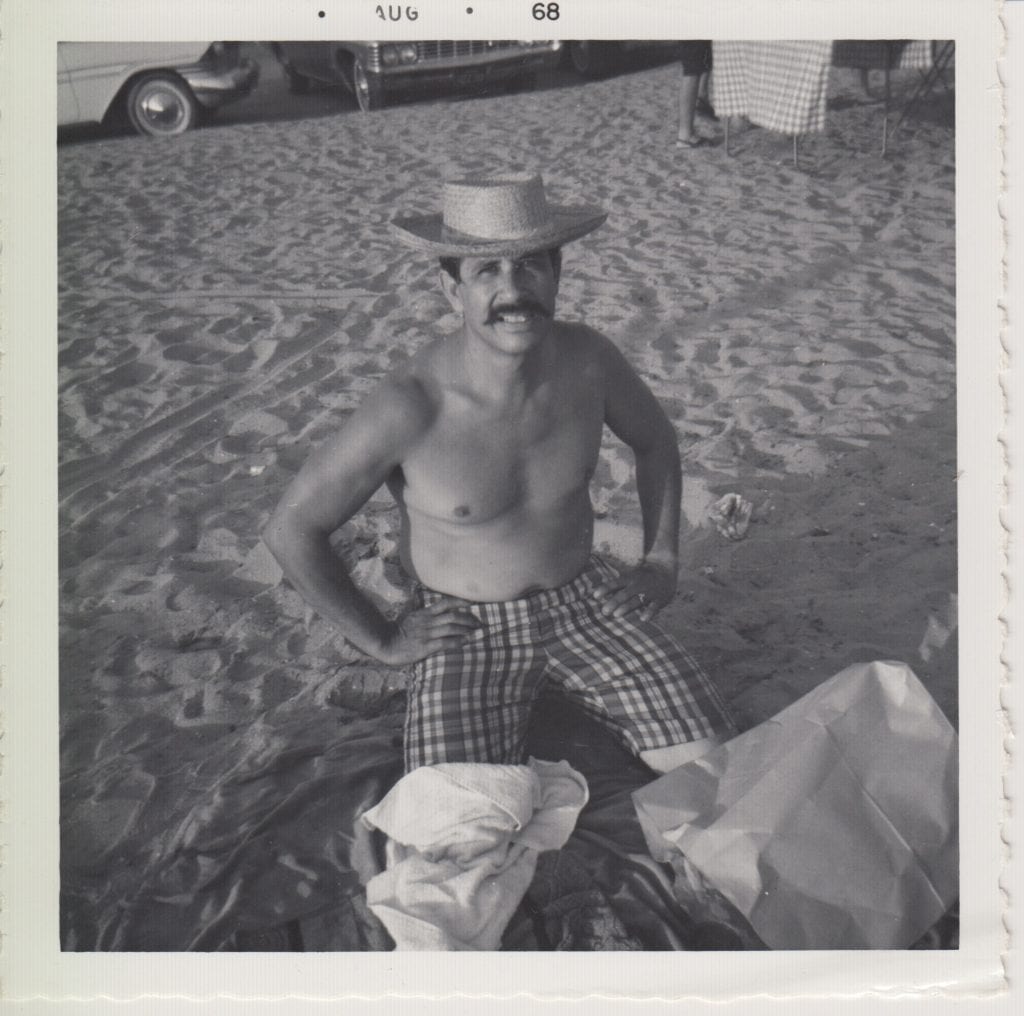

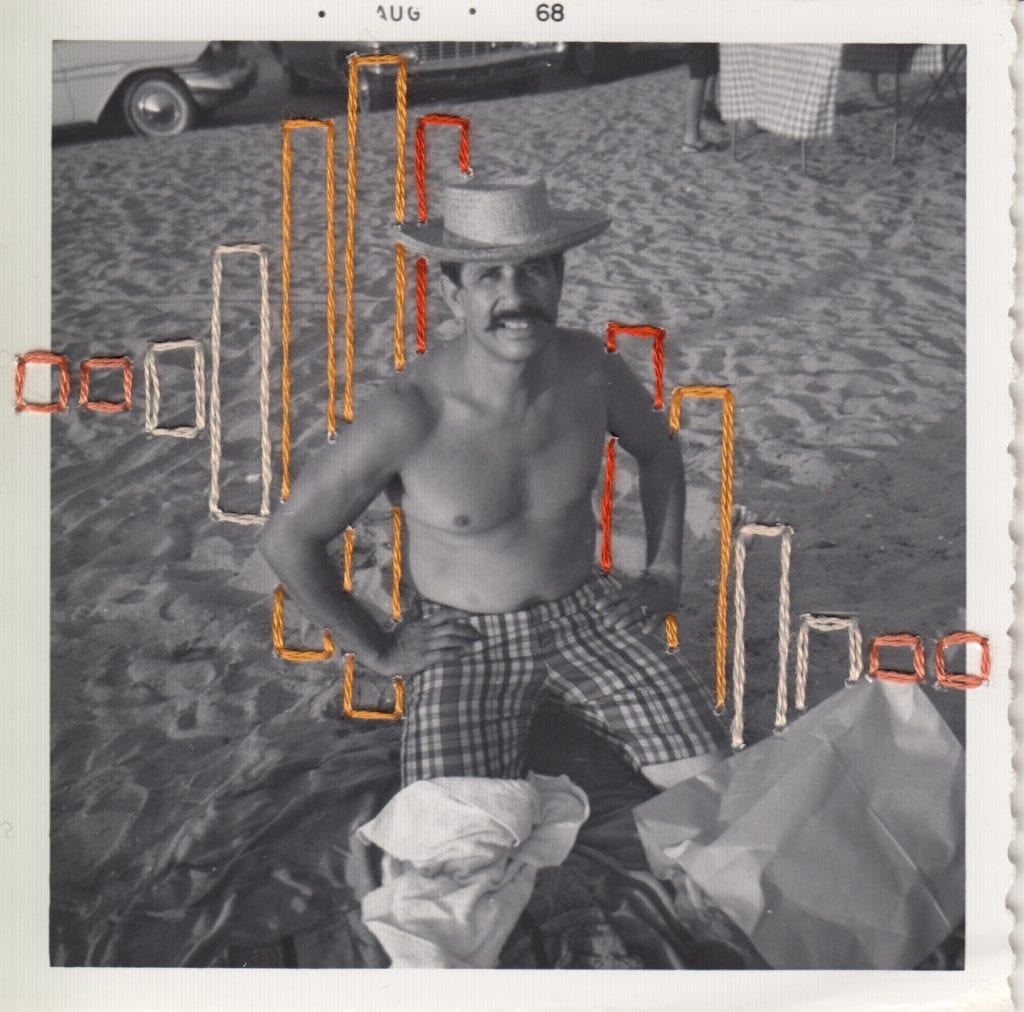

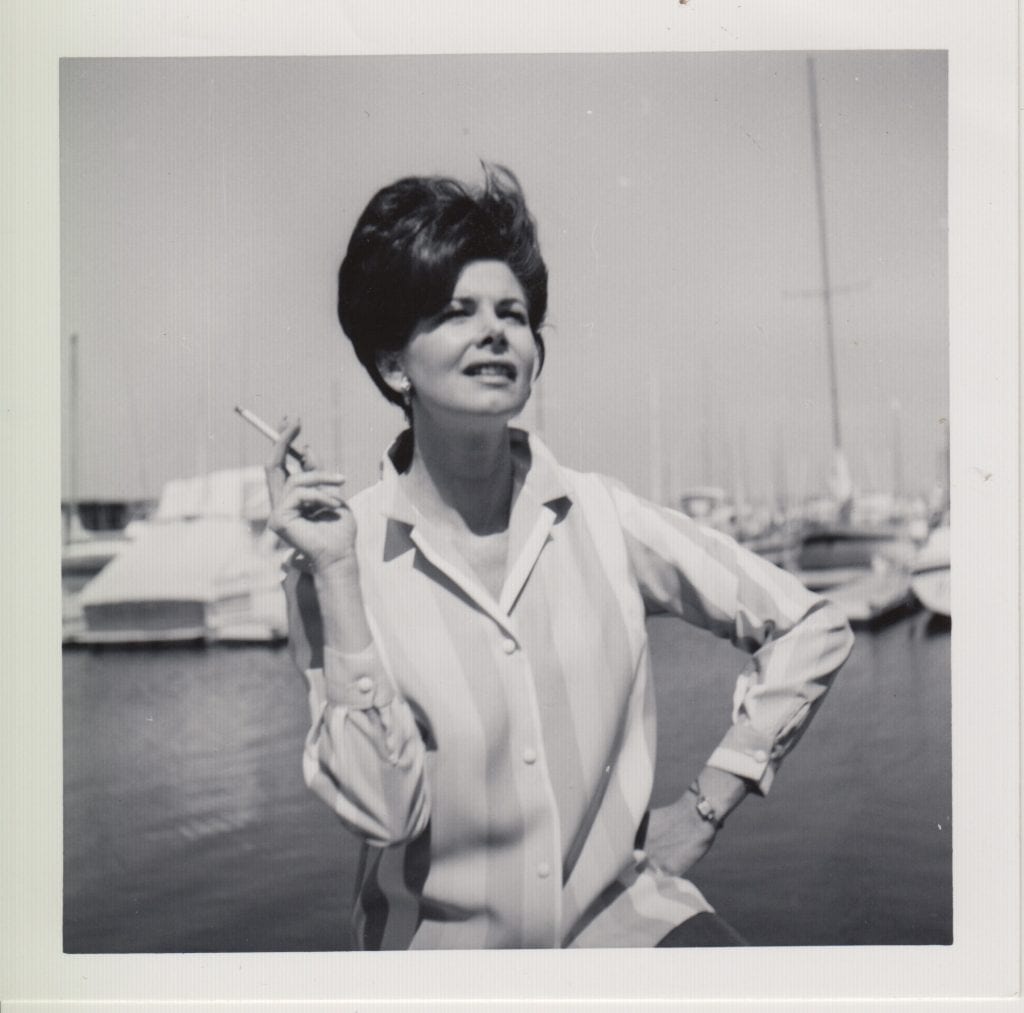

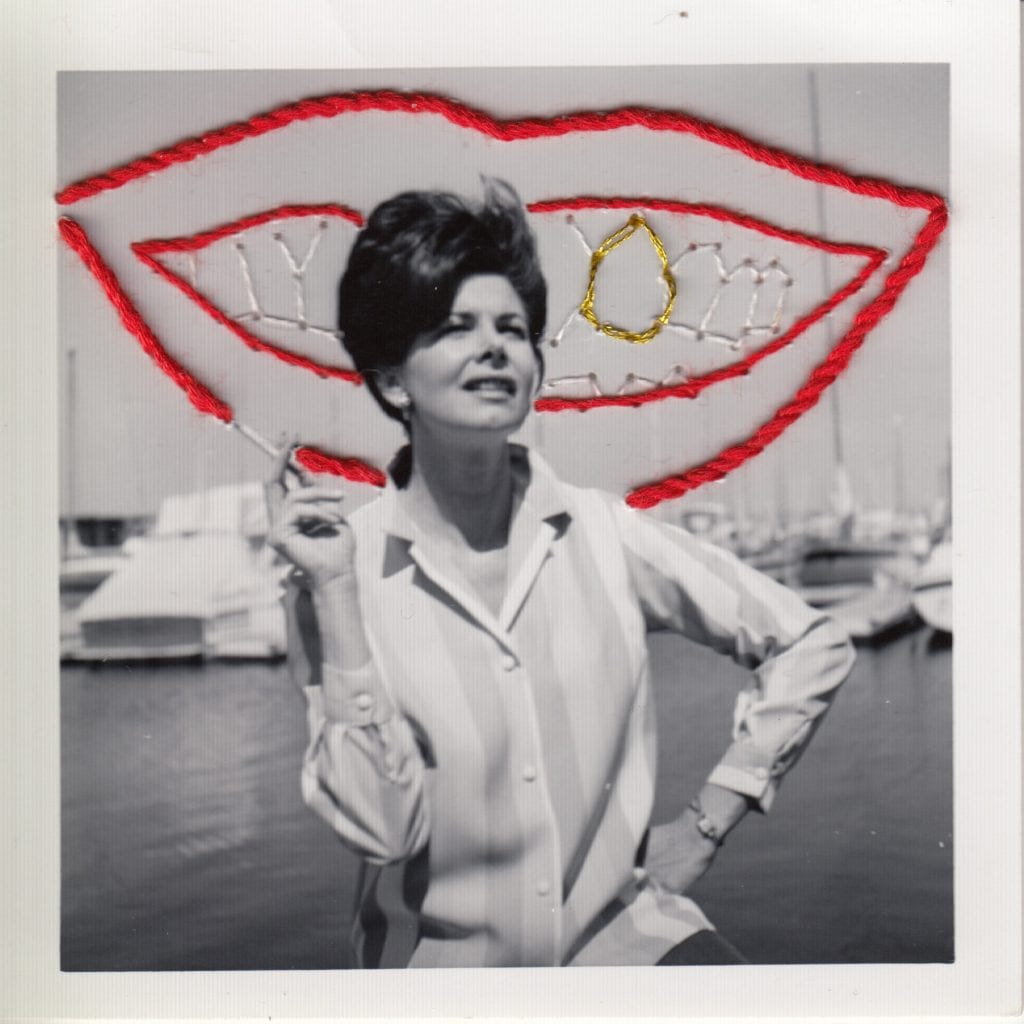

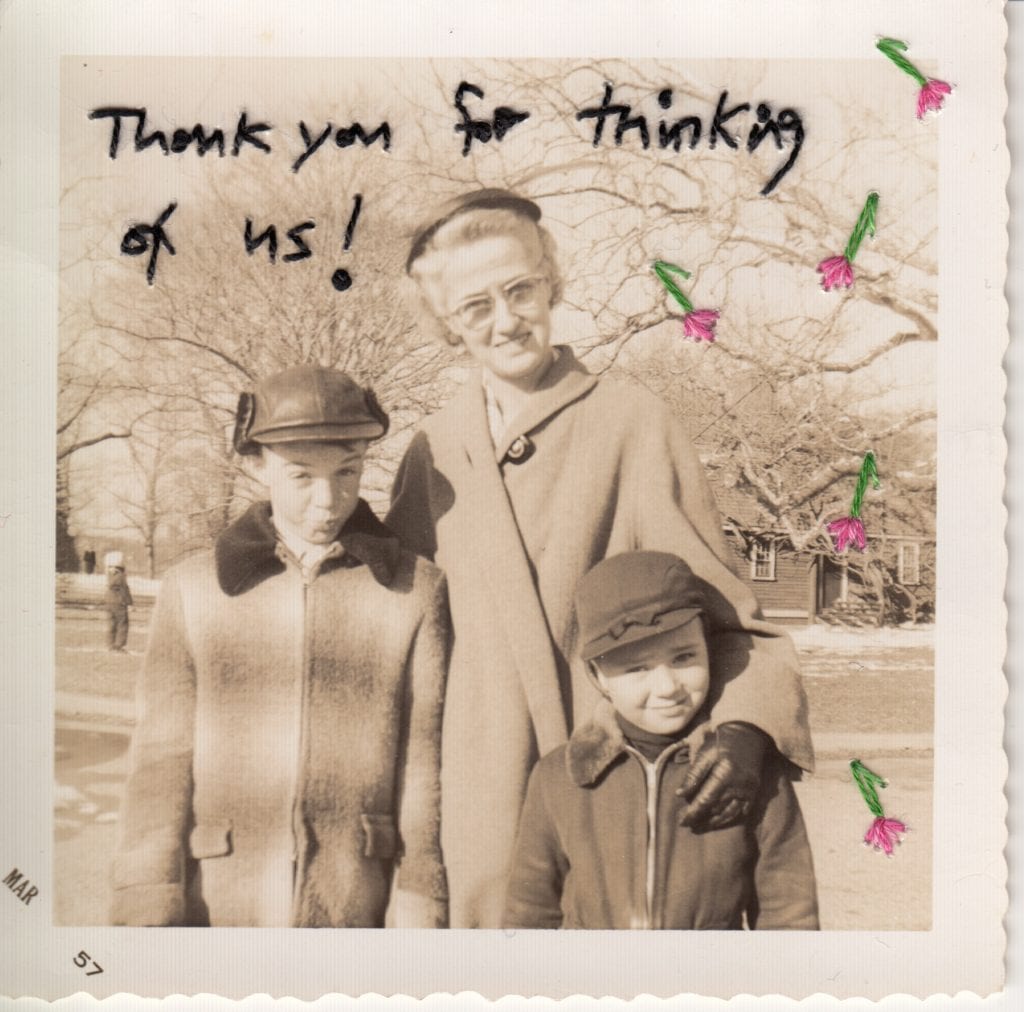

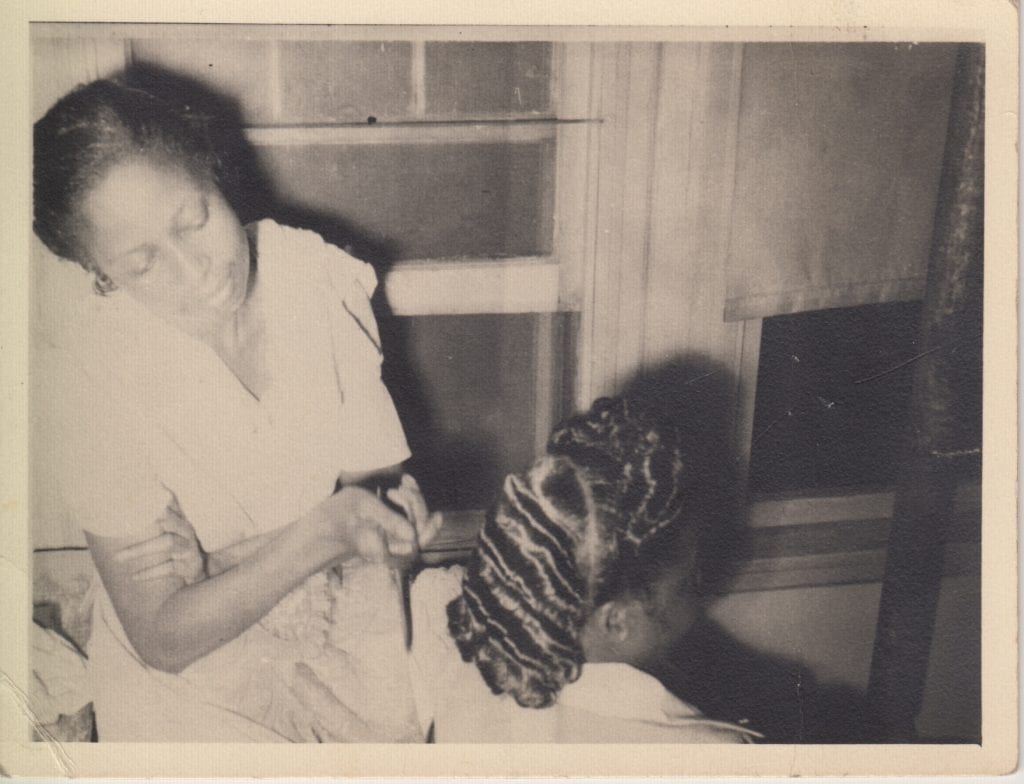

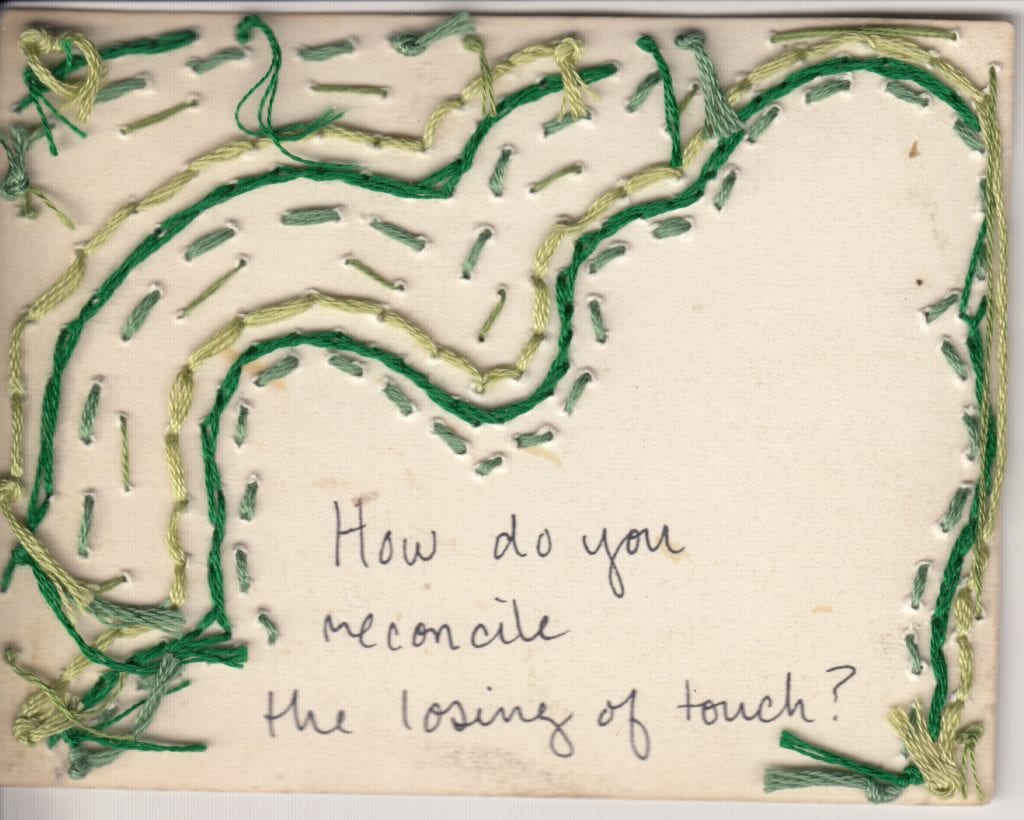

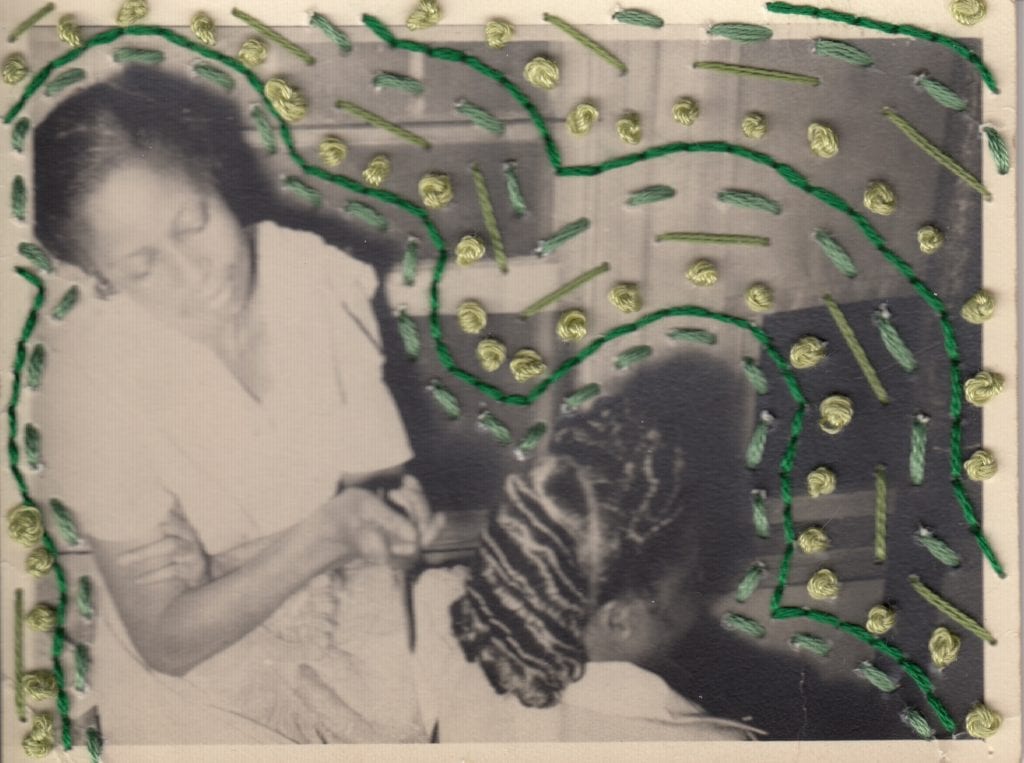

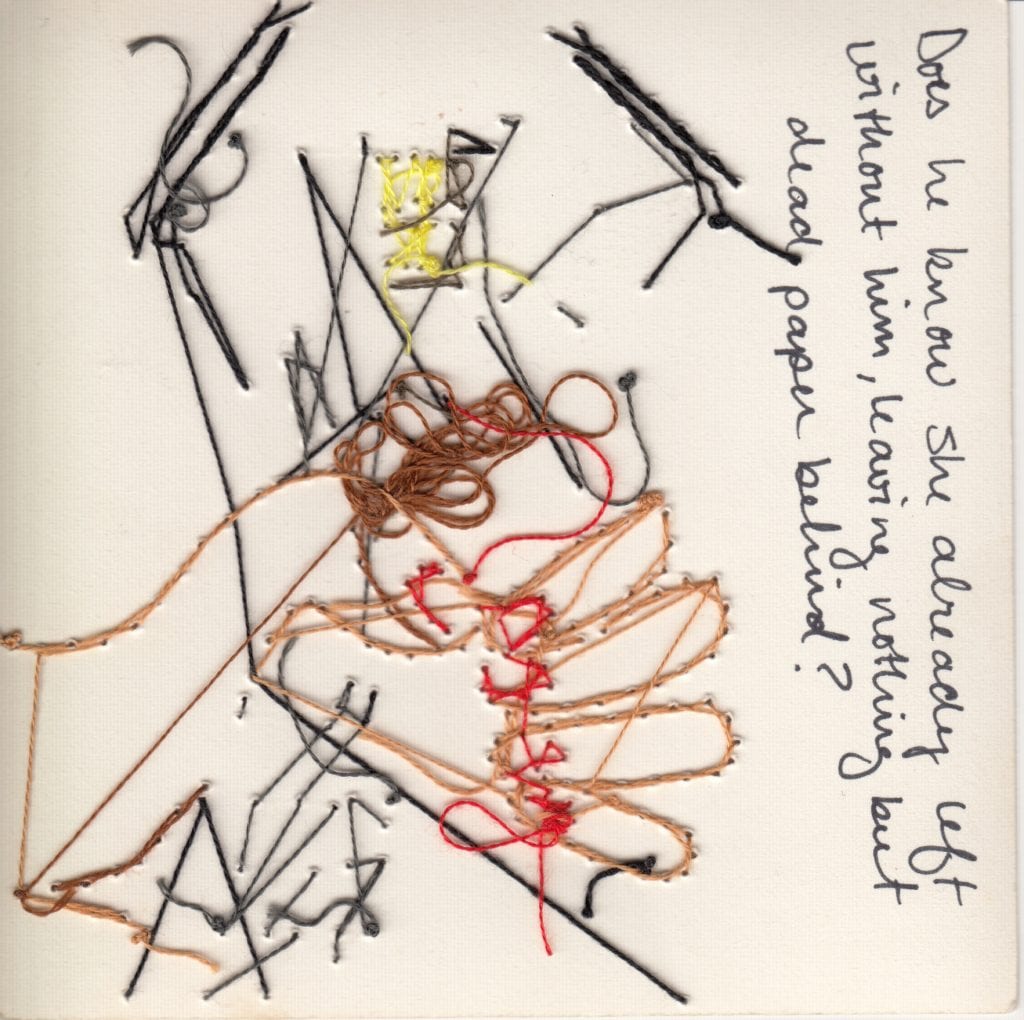

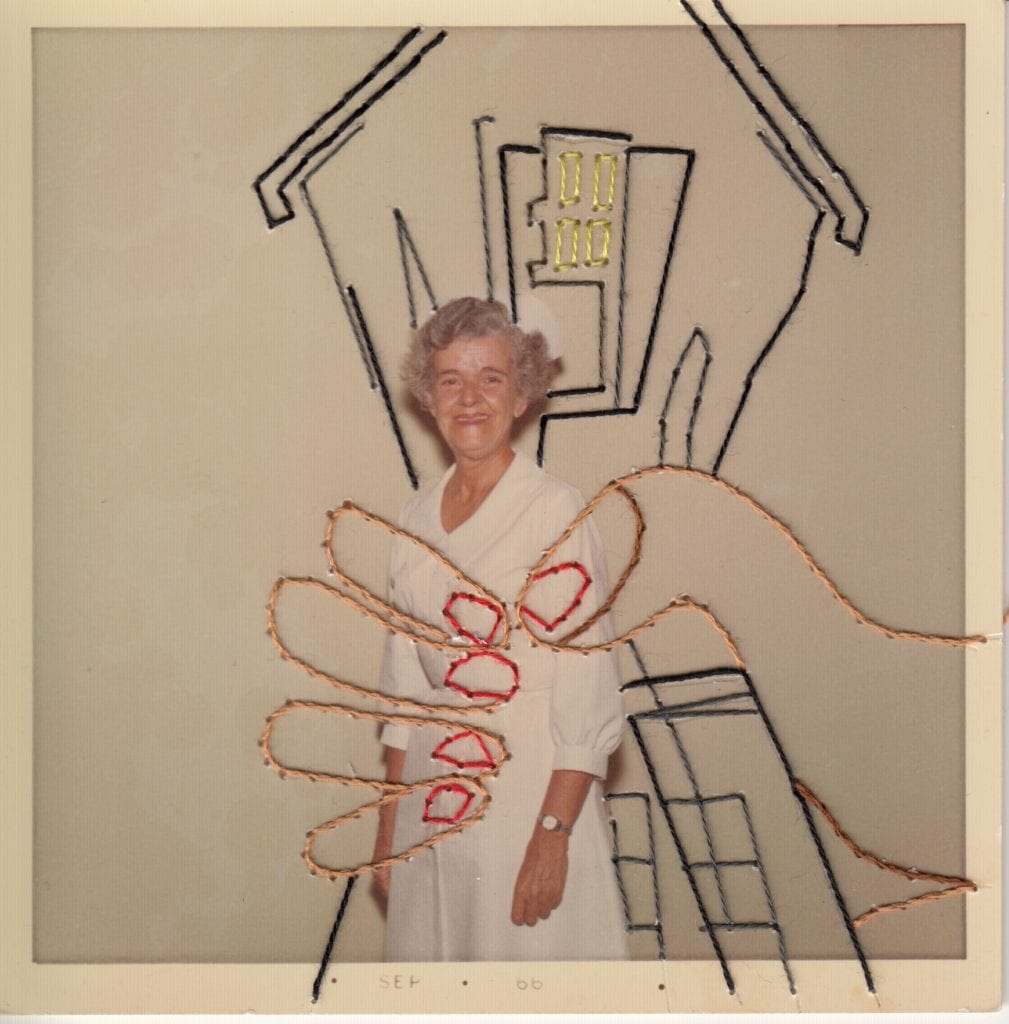

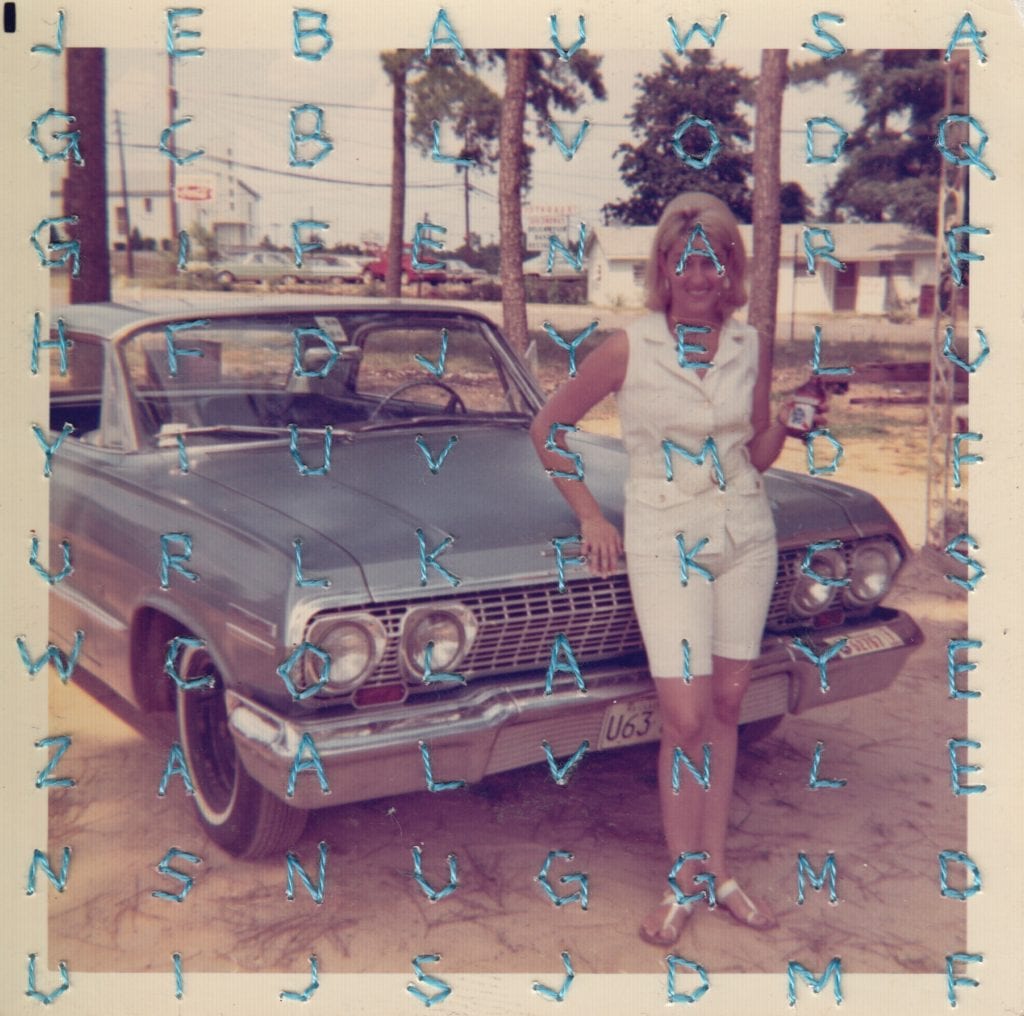

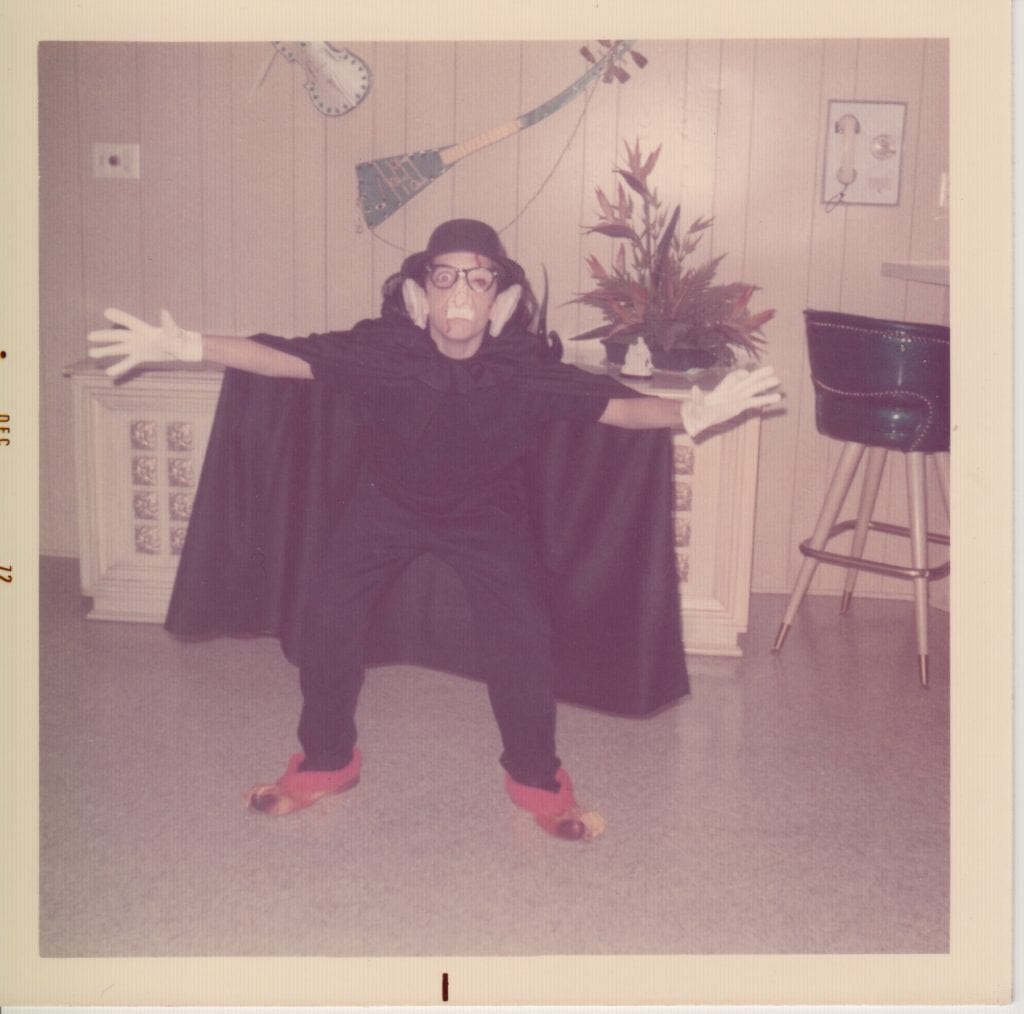

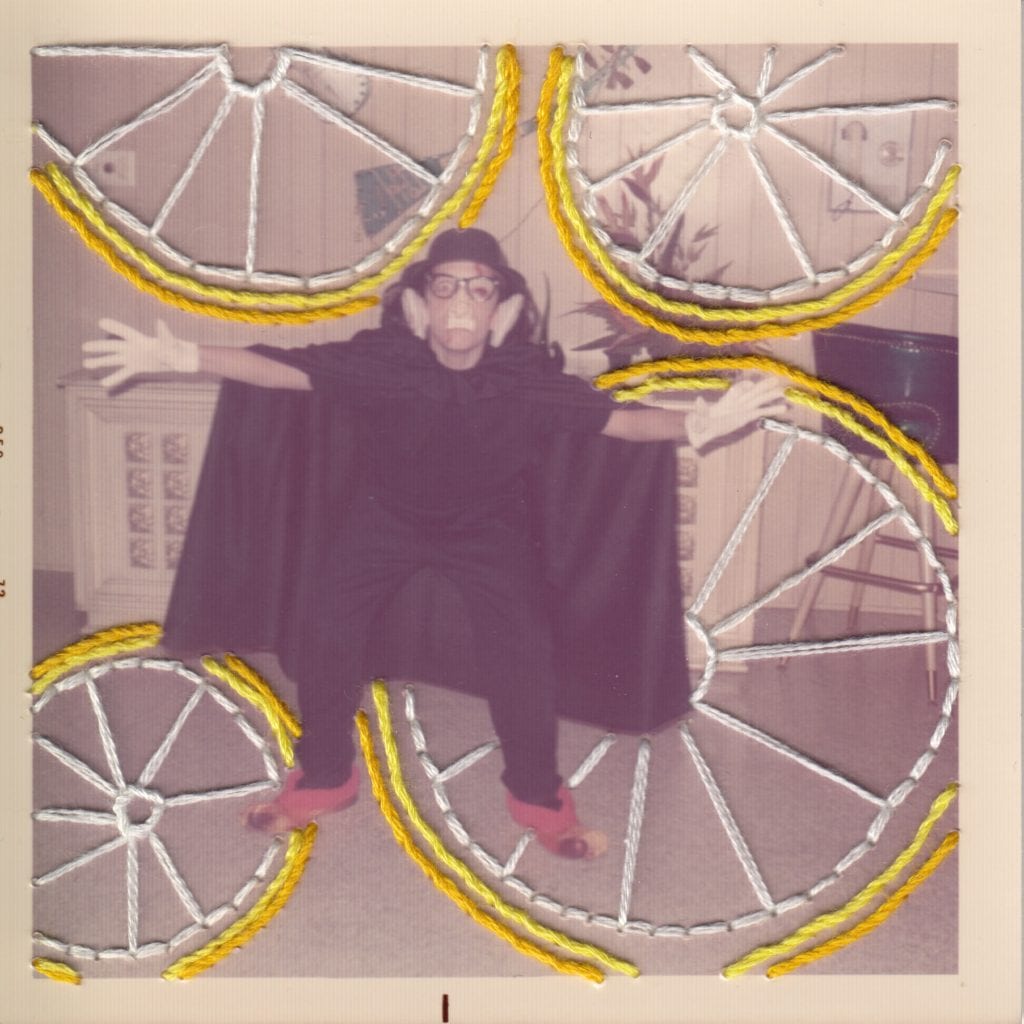

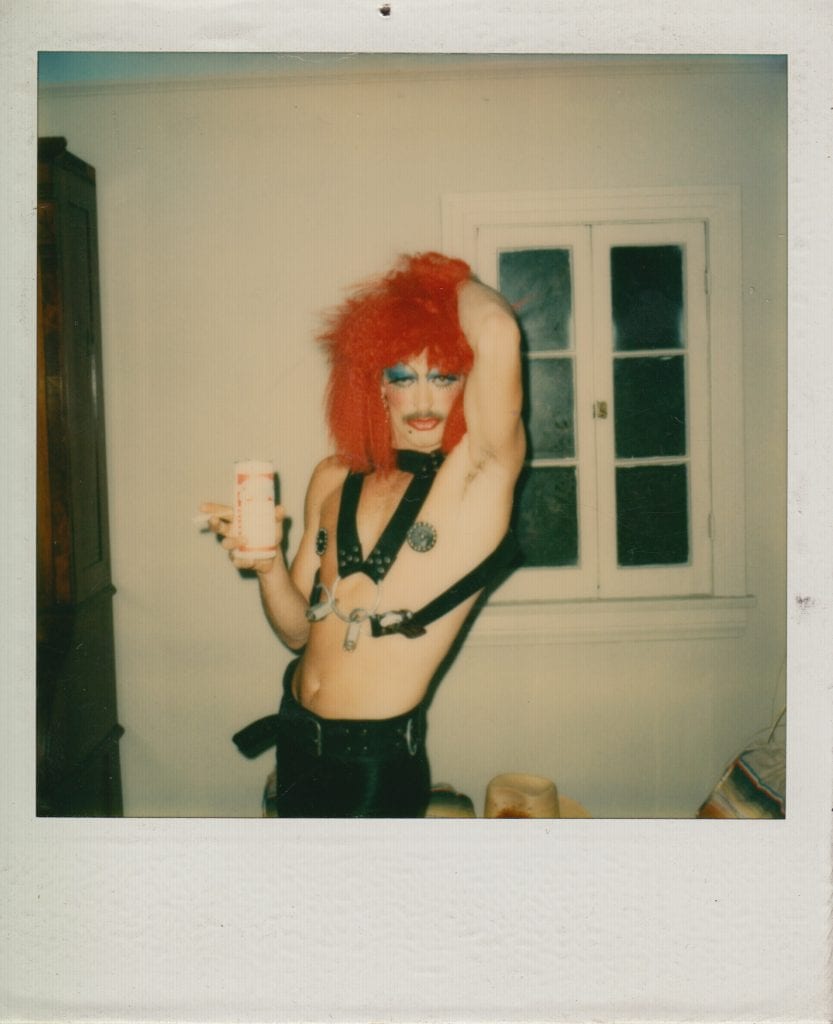

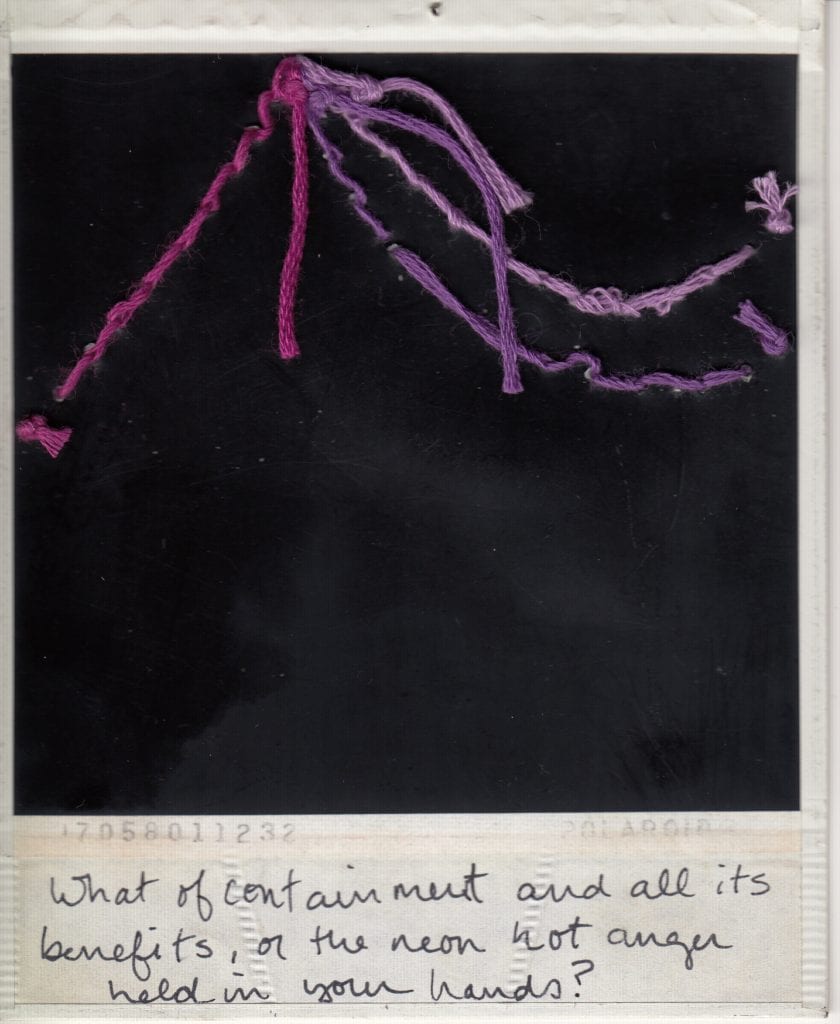

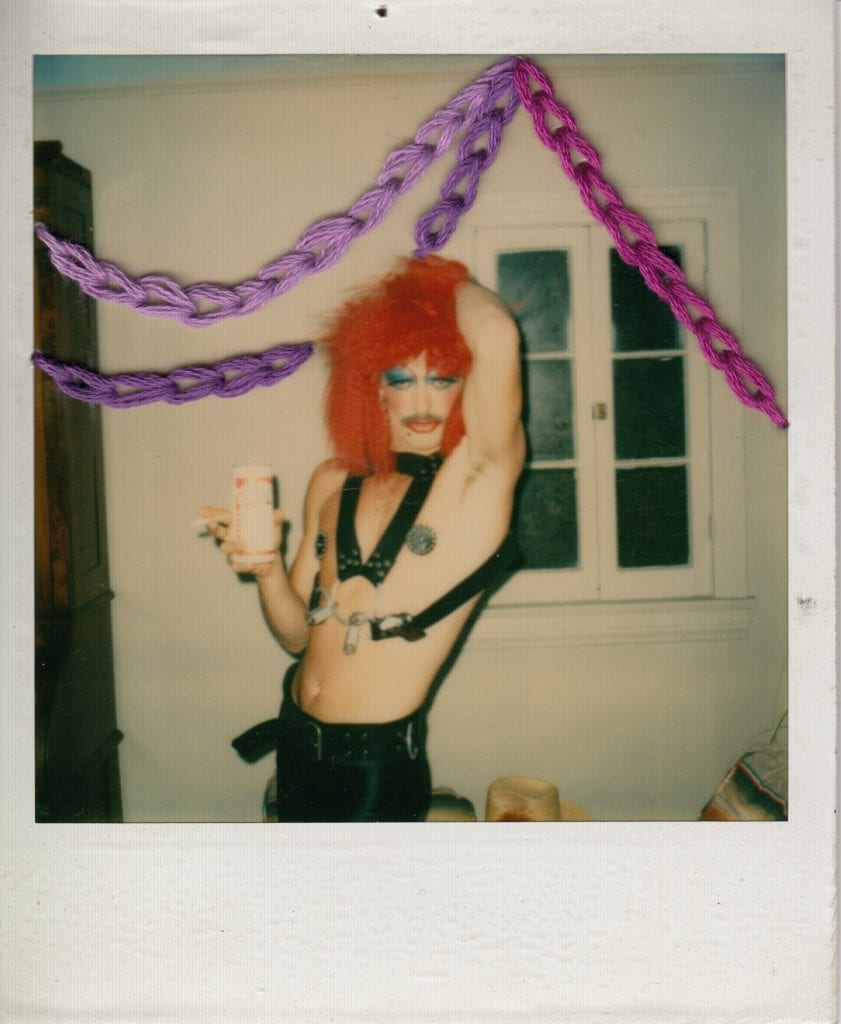

The Show Your Work series considers the human tendency to impose our own narratives on another’s truth, as well as the layered and complicated process of rewriting the present by reconsidering the past. Each image in the Show Your Work series is a previously discarded photograph dug up at an antique store or on a found-photo resale site.

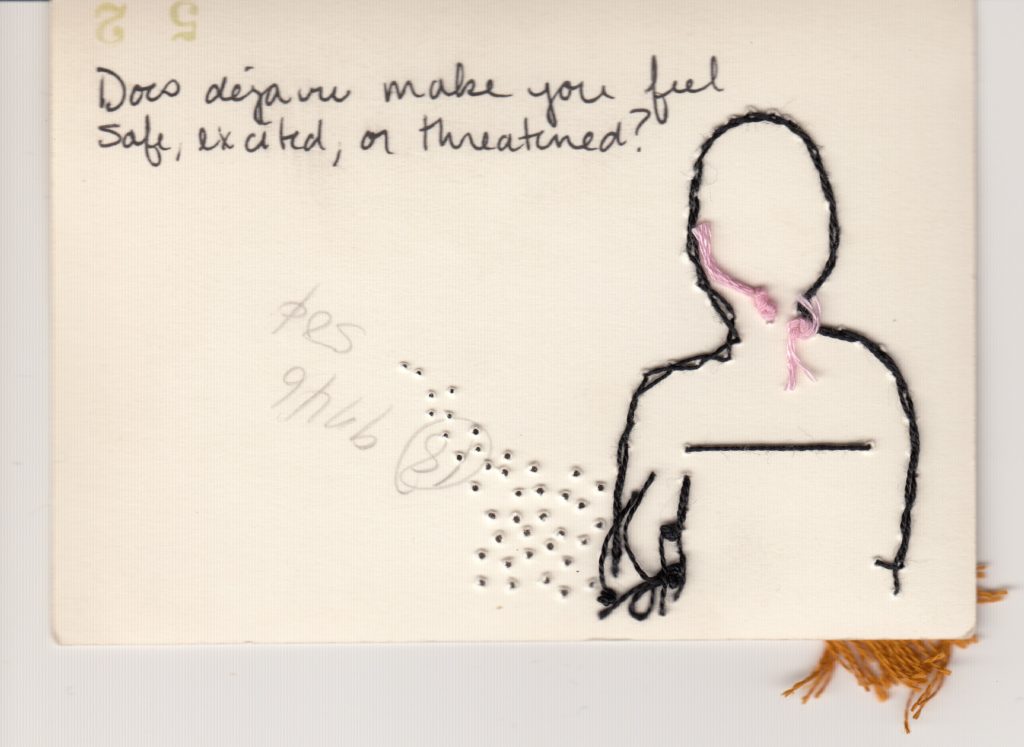

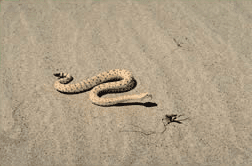

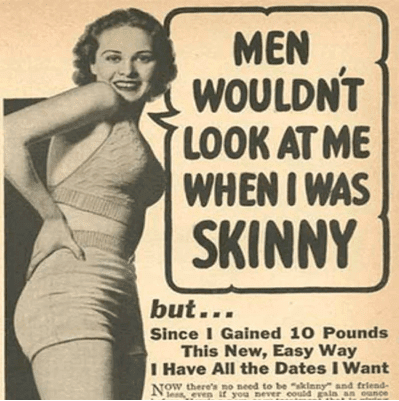

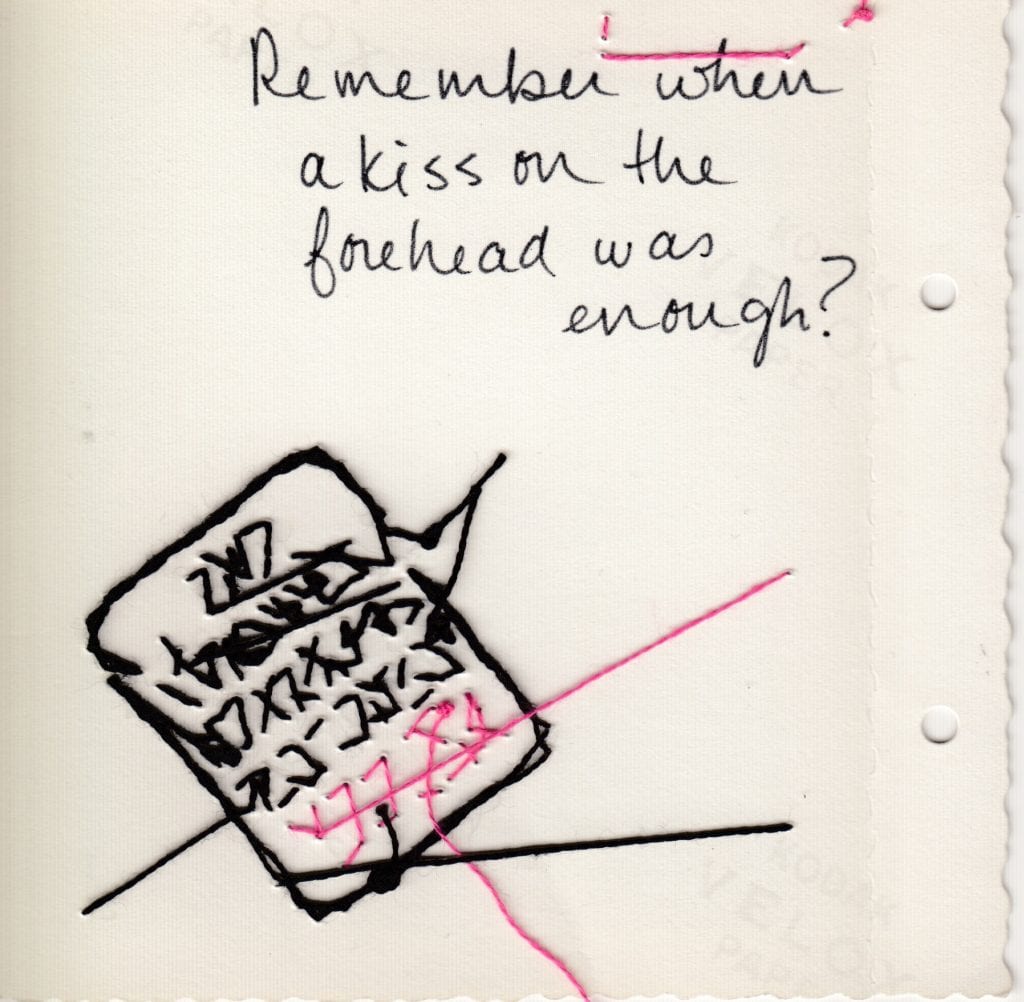

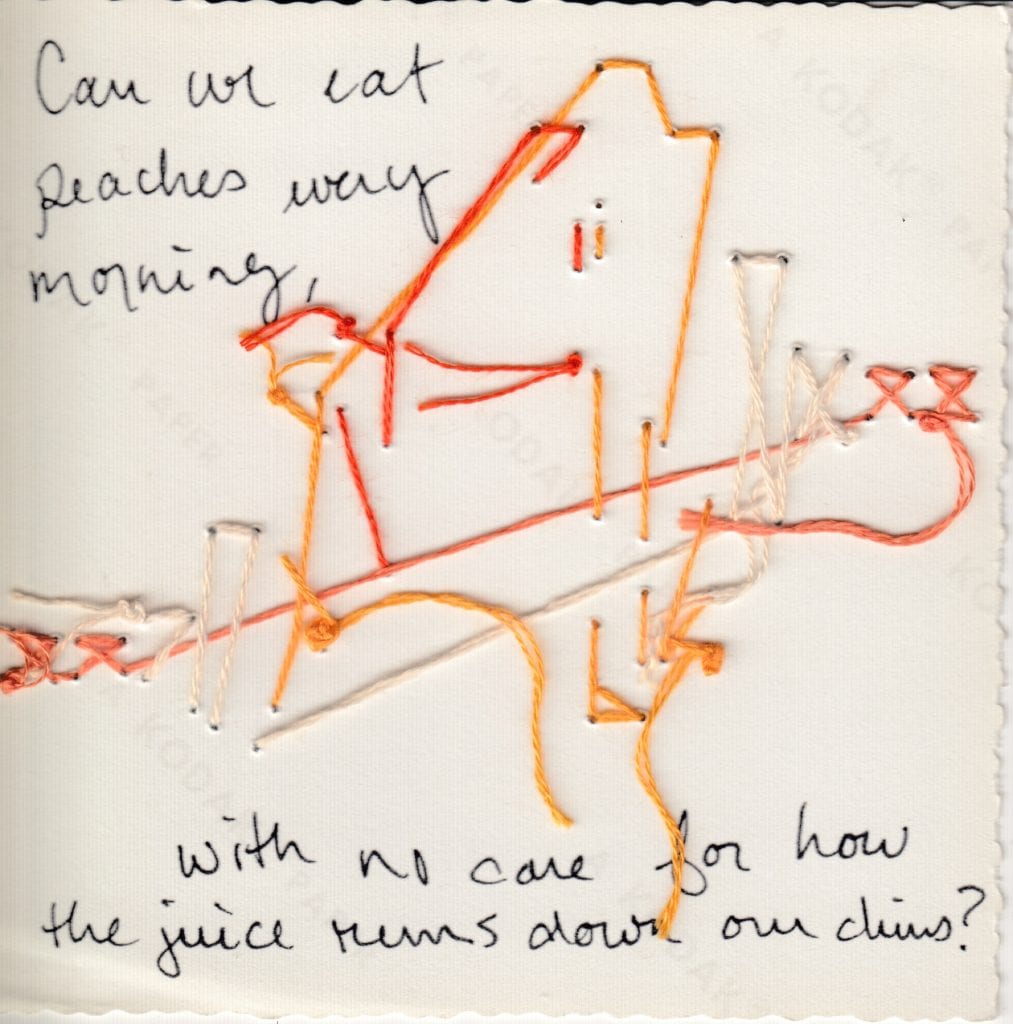

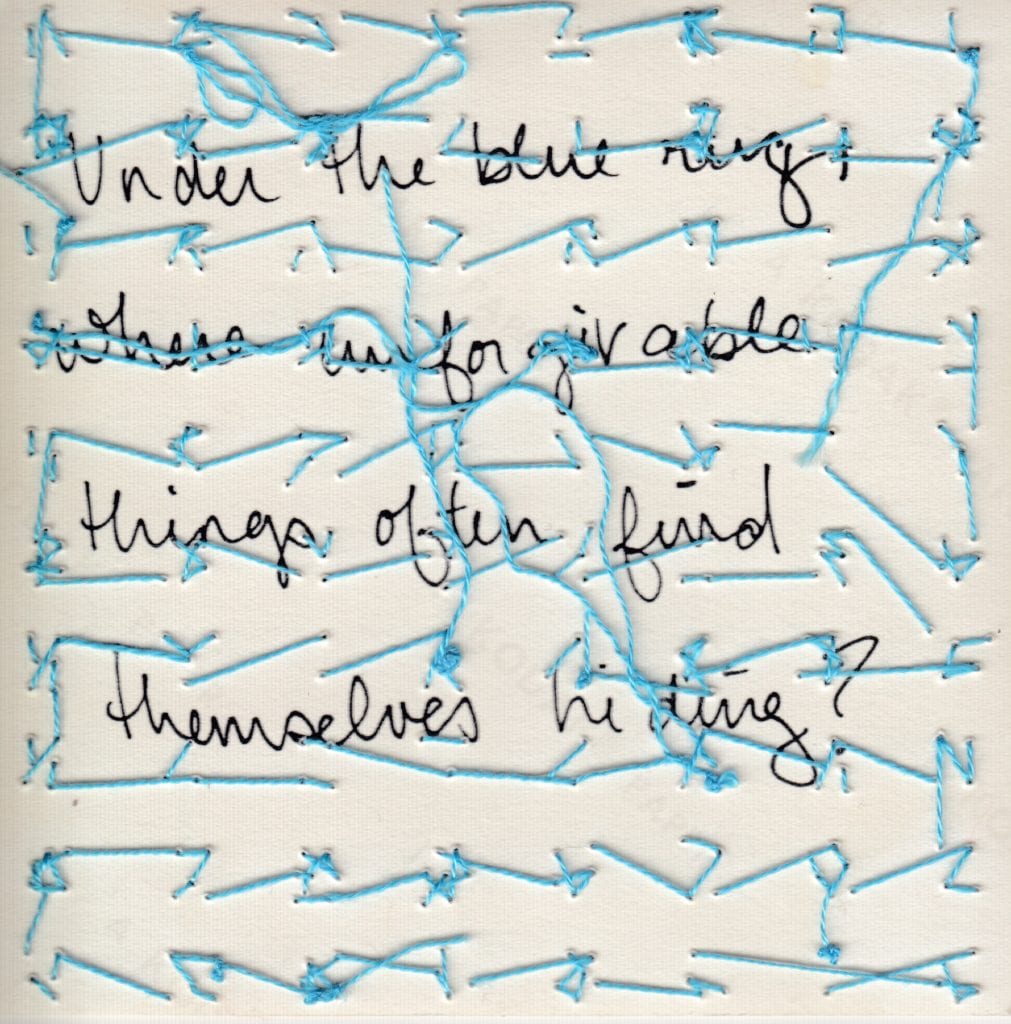

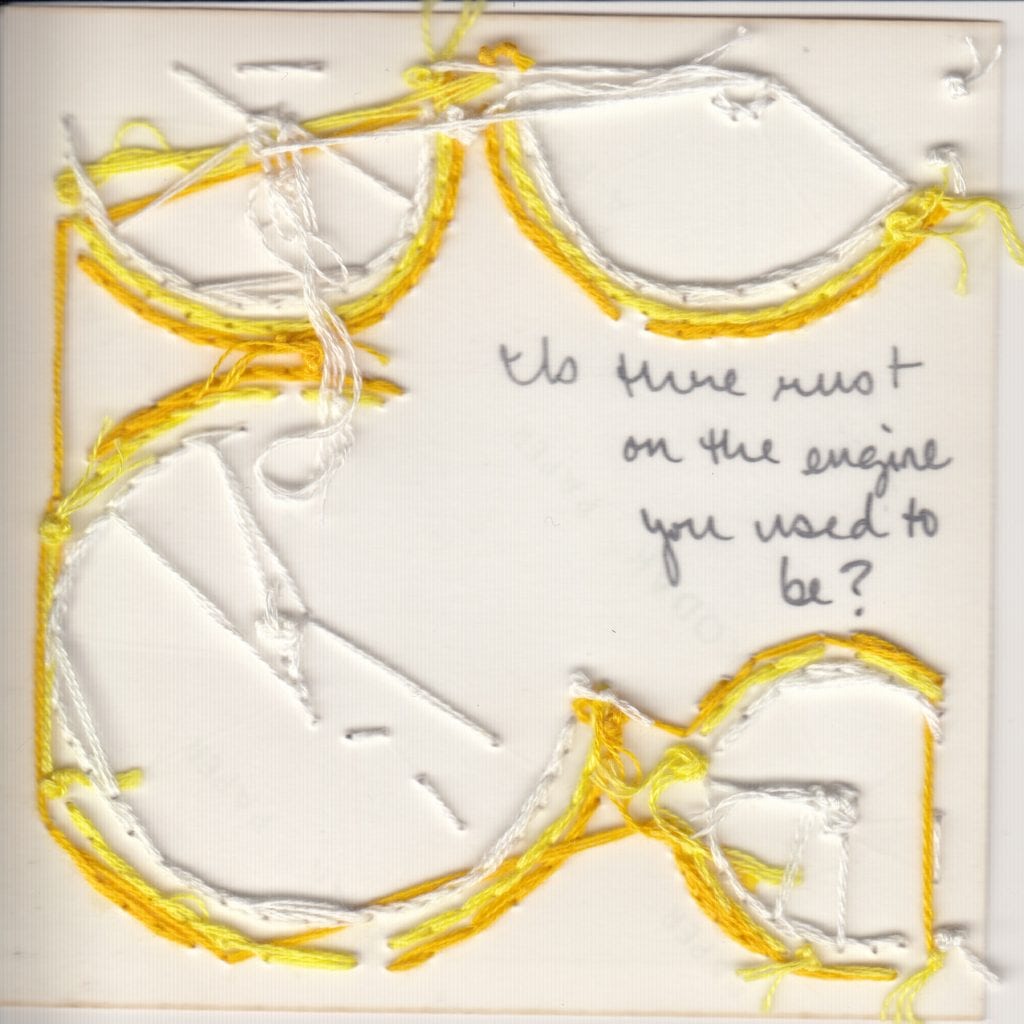

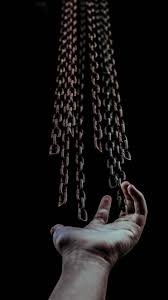

To determine what to embroider on each image, I Google-searched a question sparked by the original photograph, selected the most intriguing image that showed up in the Google results, and then embroidered that web-found image onto the original photograph.

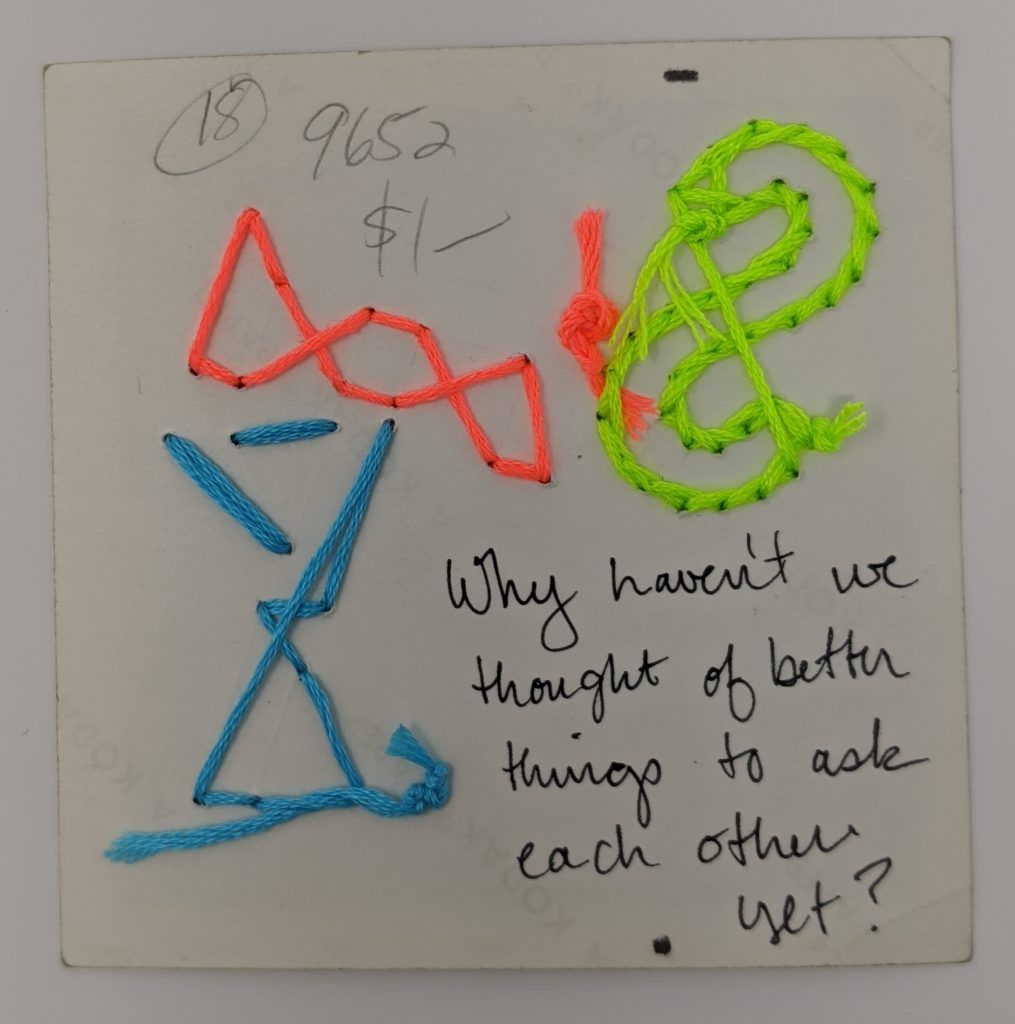

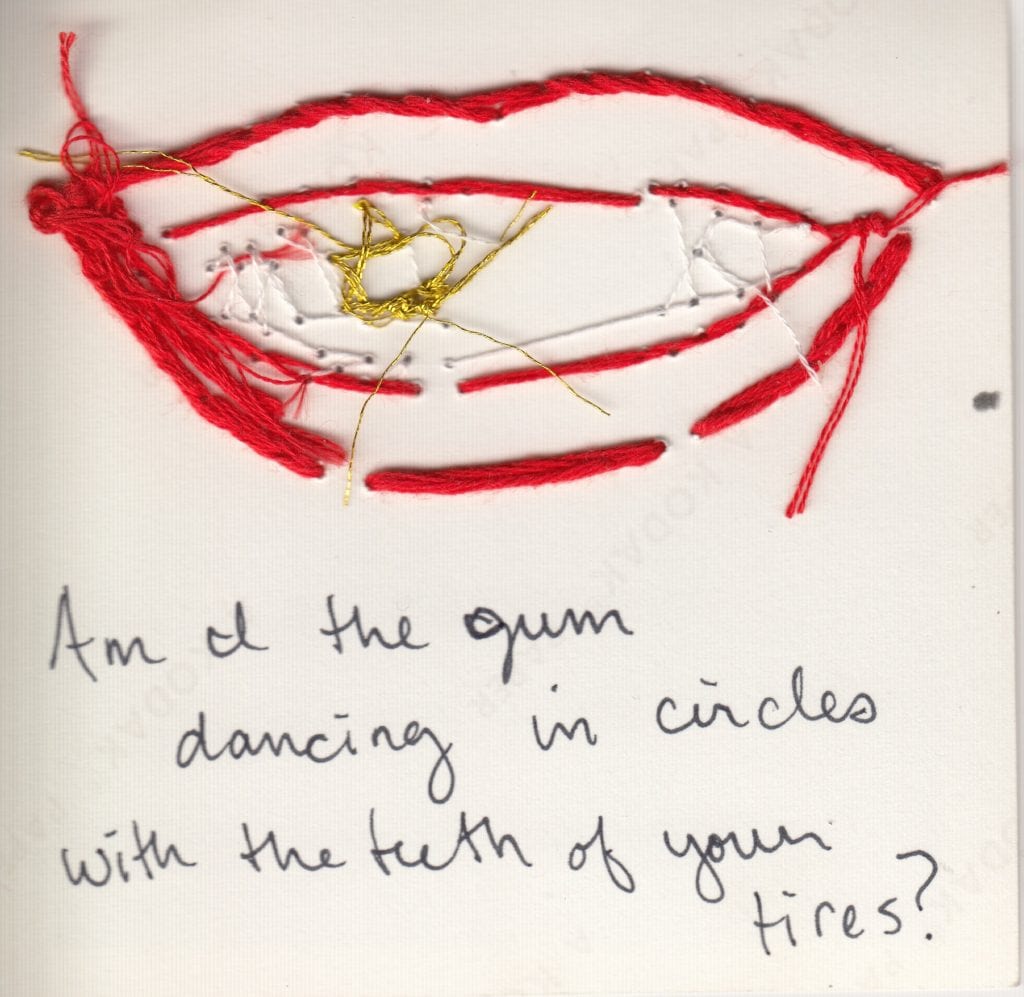

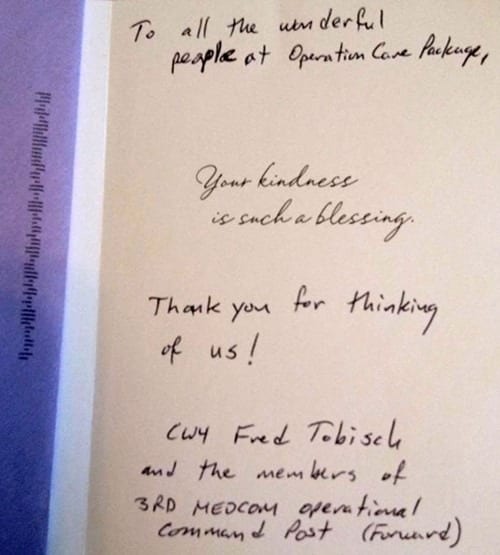

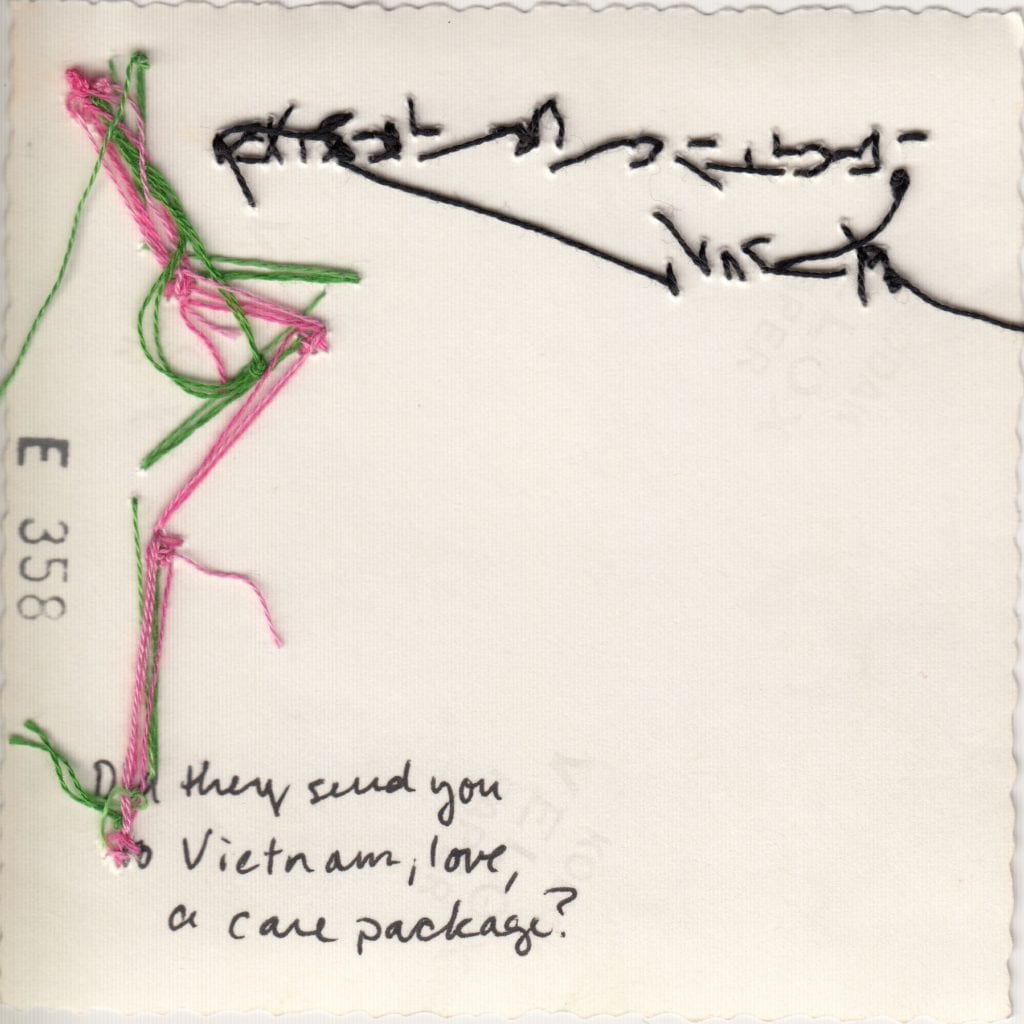

The framing methodology of double-sided glass frames encourages viewers to turn the frame around to see the back of each altered photograph—to see the work. The flip side of the photo can reveal the history of the photo, a pentimento of its years as a multi-purpose object, and hint at the many hands that have touched it. See the messy embroidery backside not often shown by artists and crafters, find the Googled question in my handwriting, and read any prior markings by previous owners of the photograph (including years, names, notes, and/or antique store sales information).

In a time that’s all about content generation, what do we do with the “content” that’s already here? This work also engages contemporary culture’s historically profound ability to divine answers almost immediately, as well as the tension and confusion that results from our very mortal inability to find the answers we are most often in search of.

This presumptuous layering work was partly inspired by photographer Cindy Sherman’s famous 1981 photograph “Untitled #93,” which, though technically not titled, she calls “The Black Sheets.” Sherman is purposefully ambiguous, leaving the viewer to make their own assumptions about the image—often vastly different from her own intent when staging the portrait. She says, “I think of that character as having just woken up from a night out on the town and she’s just gone to bed like five minutes before and the sun is waking her up and she’s got the worst hangover and she’s about to pull the sheets over her head or something and go to sleep. And other people look at that [photograph] and think she’s a rape victim.” Why do we see what we see? How does our perspective get it wrong? What does it get it right? Is there a space in between these extremes and, if so, how do we hold that space for ourselves and others?