I spent most of January in an escapist headspace, burrowing down into several subjects, my fascination with which have taken me by surprise.

1) Richard Yates. I read Revolutionary Road in 2008 when the movie came out because my tween brain imprinted on Titanic-era Kate and Leo in 1997 and I’m pretty much subconsciously committed to following them in a space ship to Mars if they were featured as star-crossed lovers in its alien-infested bowels.

But. I never watched Revolutionary Road the movie for some reason? Probably because I read the book first and it was devastating; too devastating to see on screen right afterward. Fast forward almost 13 years later, the movie’s on HBO Max and with all this quarantine time on my hands, I gave it a crinoline-skirted whirl and… god damn. Devastating, yes indeed, but I was surprised at how differently I thought of the characters and the plot with some years as an adult under my belt. (APRIL, I KNOW, IT SUCKS YOU CAN’T SELF ACTUALIZE BECAUSE OF THINGS OUTSIDE YOUR CONTROL, BUT YOU LUCKY BITCH, JUST ENJOY YOUR HOUSE AND WORK-FREE LIFE OMFG.)

Perhaps my bleak outlook is quarantine related. Or could it be because the movie is different from the book? I bought a three-book tome of Richard Yates’ work and decided to find out. This turned out to be the biggest January 2021 gift of all! What a cynical, destructive, brutal, little worm Revolutionary Road is. 😍 Like the girl-smirking-at-house-fire meme in book form. I love it, and I find such unrepentant catharsis in how slowly but surely Yates dismantles each character with the kind of rage-eyed honesty no one wants to be in front of but, if you see the people the way he does, feels so rewarding and relieving to watch.

And how he does it is startling. Funny almost. You can’t even see it coming. Example: The following savory paragraph about how the children can sleep comfortably now that their parents have stopped fighting (because mom and dad are high on their unrealistic self-deluded fantasy that will eventually kill someone but we’ll get there soon enough!).

“They could lie drowsing now under the sound of kindly voices in the living room, a sound whose intricately rhythmic rise and fall would slowly turn into the shape of their dreams. And if they came awake later to turn over and reach with their toes for new cool places in the sheets, they knew the sound would still be there—one voice very deep and the other soft and pretty, talking and talking, as substantial and soothing as a blue range of mountains seen from far away.”

Then, next paragraph, like a slap in the face from a surly sugar plum fairy:

“This whole country’s rotten with sentimentality,” Frank said one night…

HA!

2) Dennis Rodman. I know, girl! I don’t know! Whyyy?

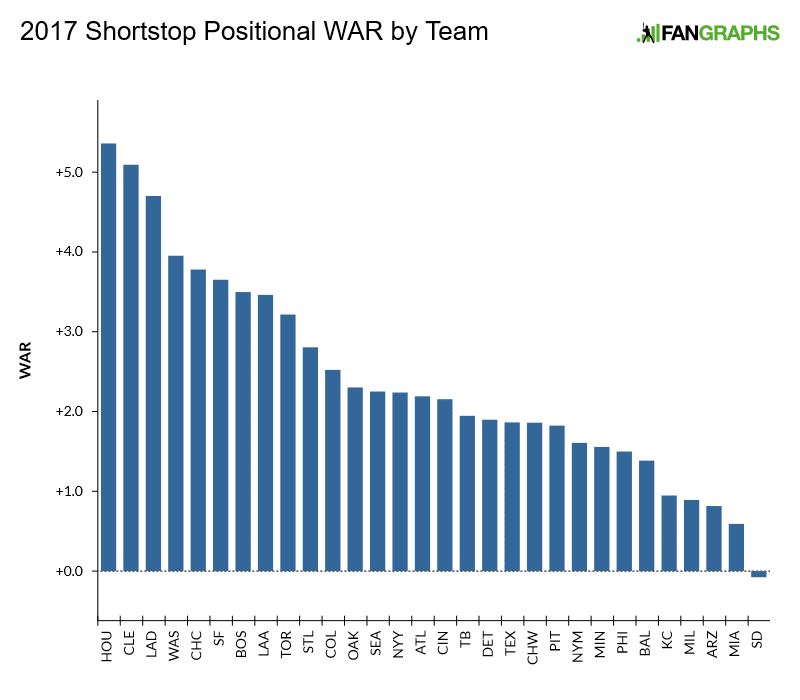

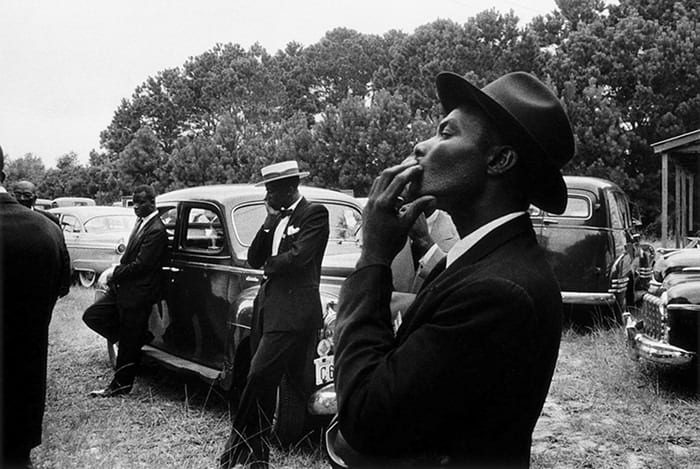

This minor obsession was inspired by another thing we finally watched: The Last Dance docu-series, which chronicles the 1990s Chicago Bulls as they went for their sixth and final title. At first I was really grooving on Scottie Pippen, learning about his playing style, often relegated to the second paragraph (rightfully so) behind Michael Jordan (GOAT). Then I met Dennis “The Worm” Rodman. Like, basketball Dennis Rodman. I’m so compelled by him! I’m trying to figure out why? I love the way he played basketball, I know that much. Gutter ball go-getter, beast hunter of the rankest of rebounds, trash-talking trash man king of the trash can people…

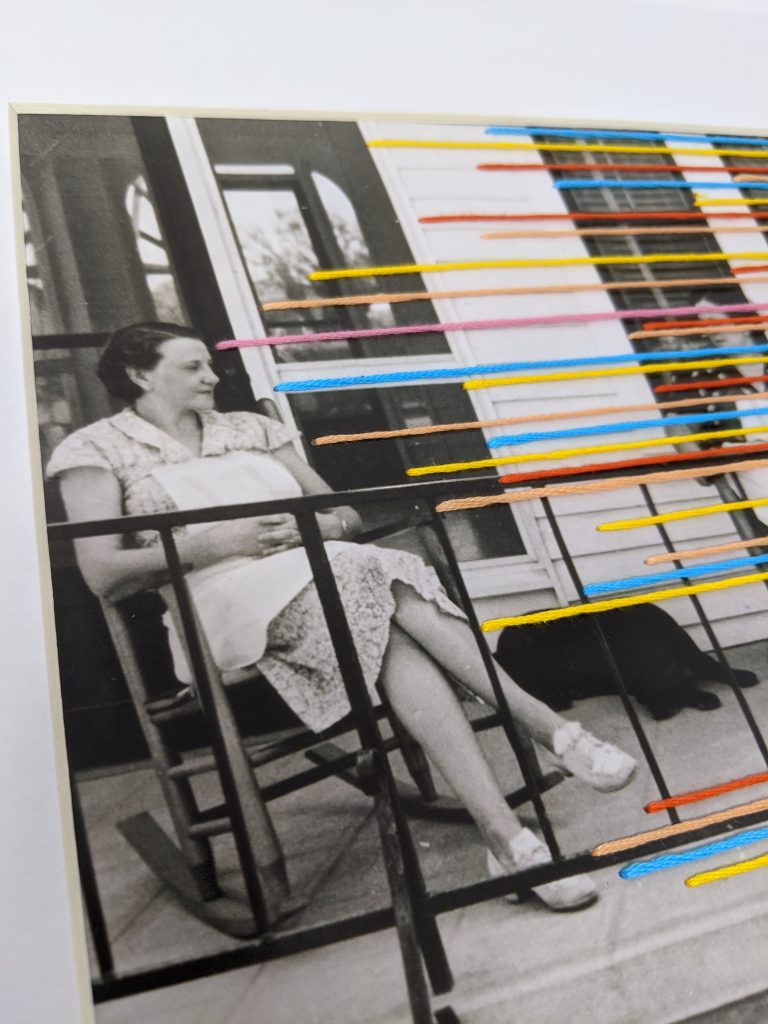

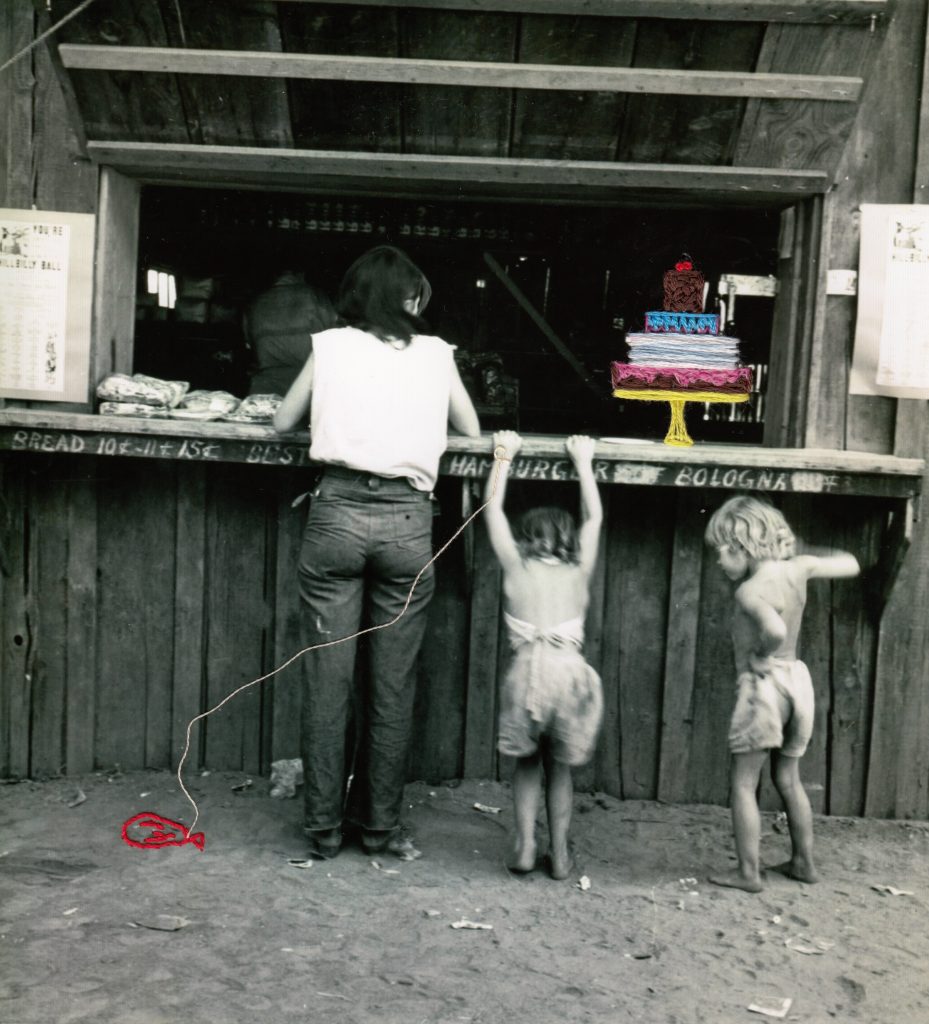

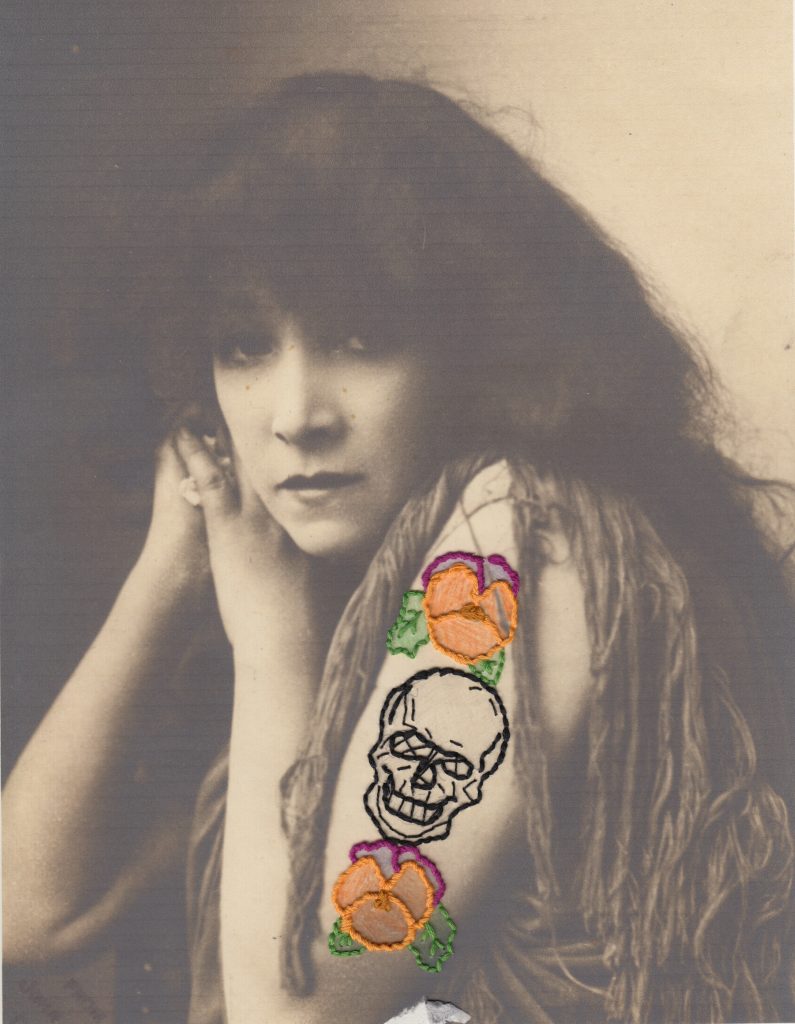

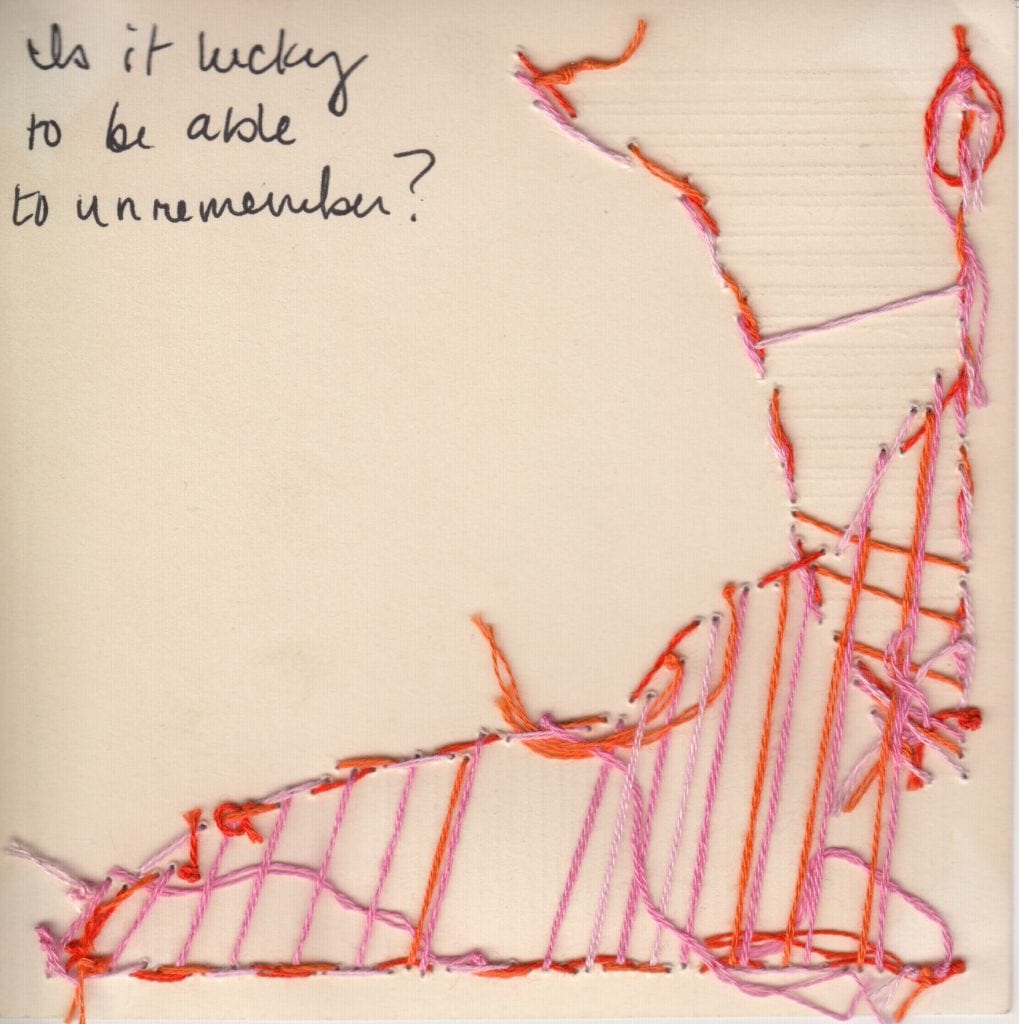

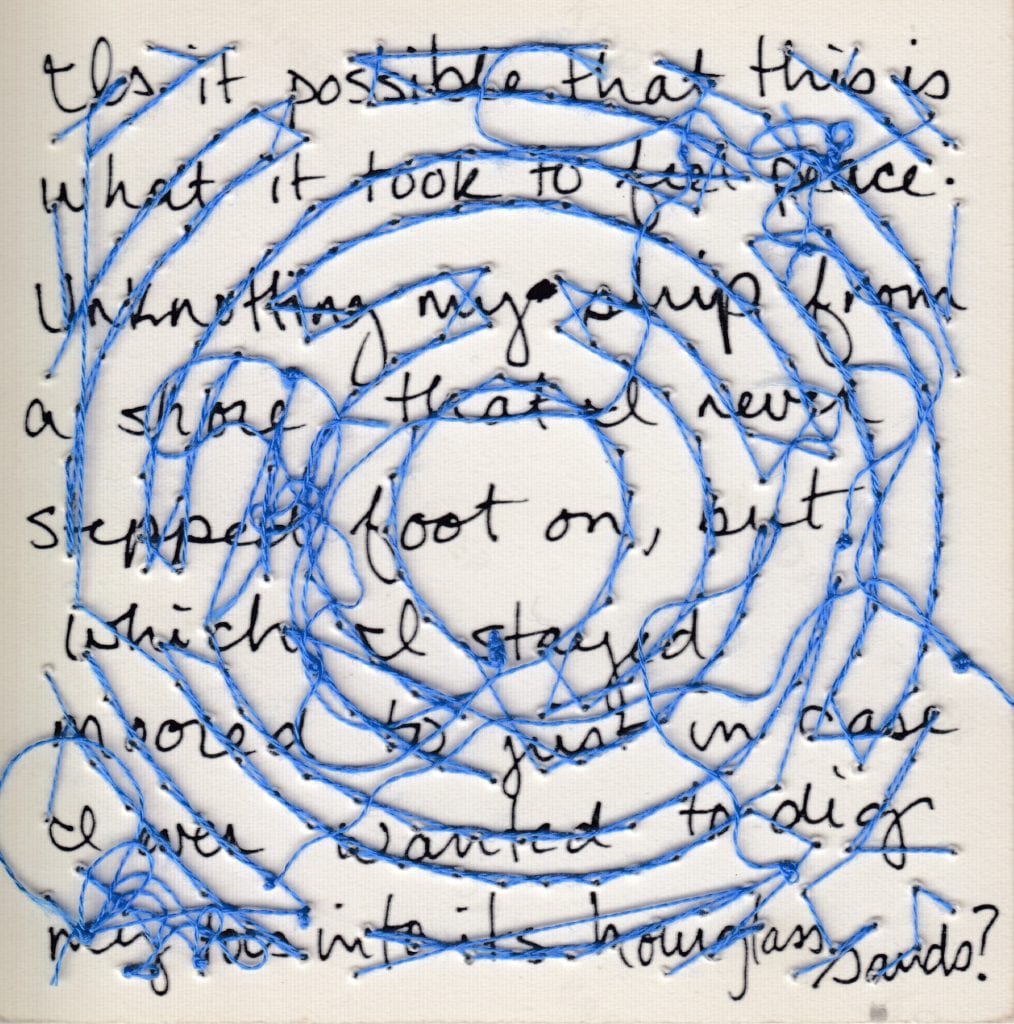

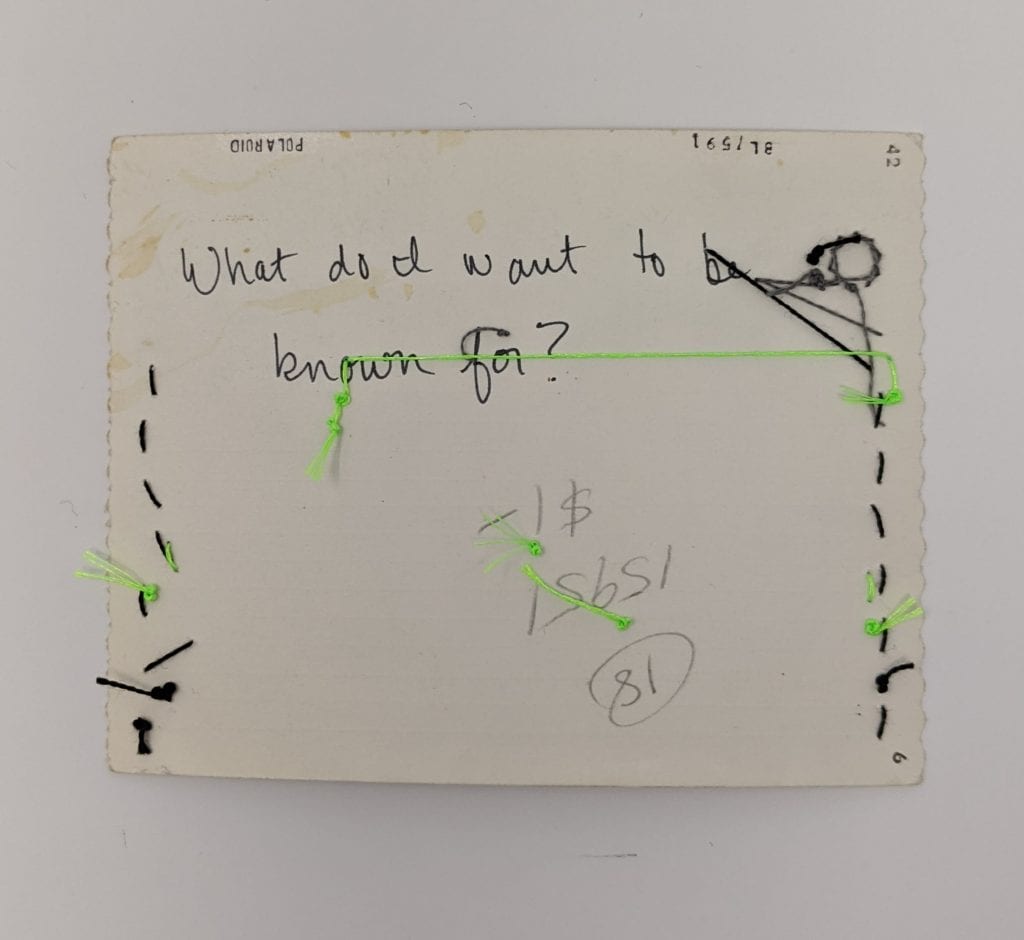

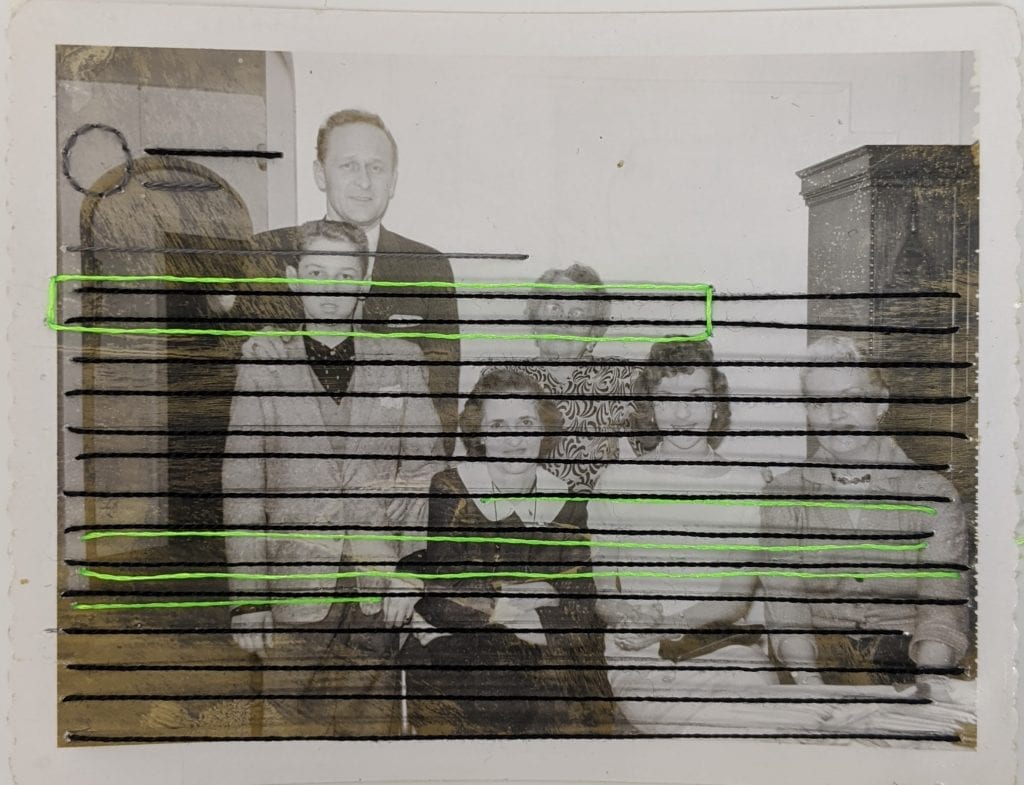

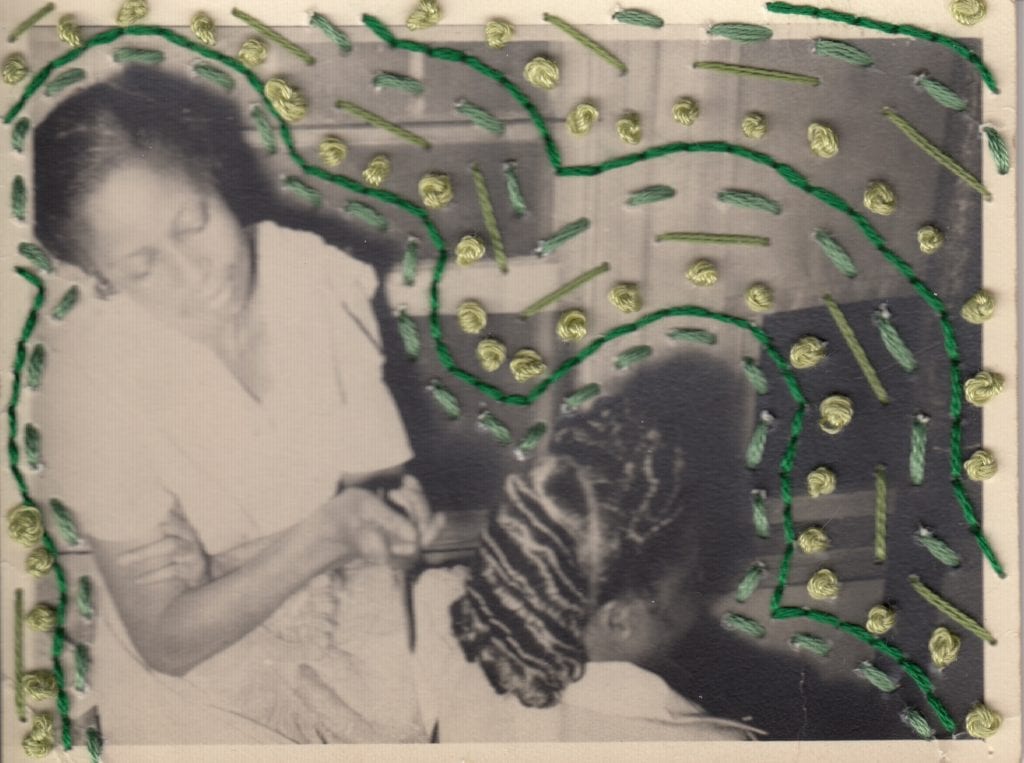

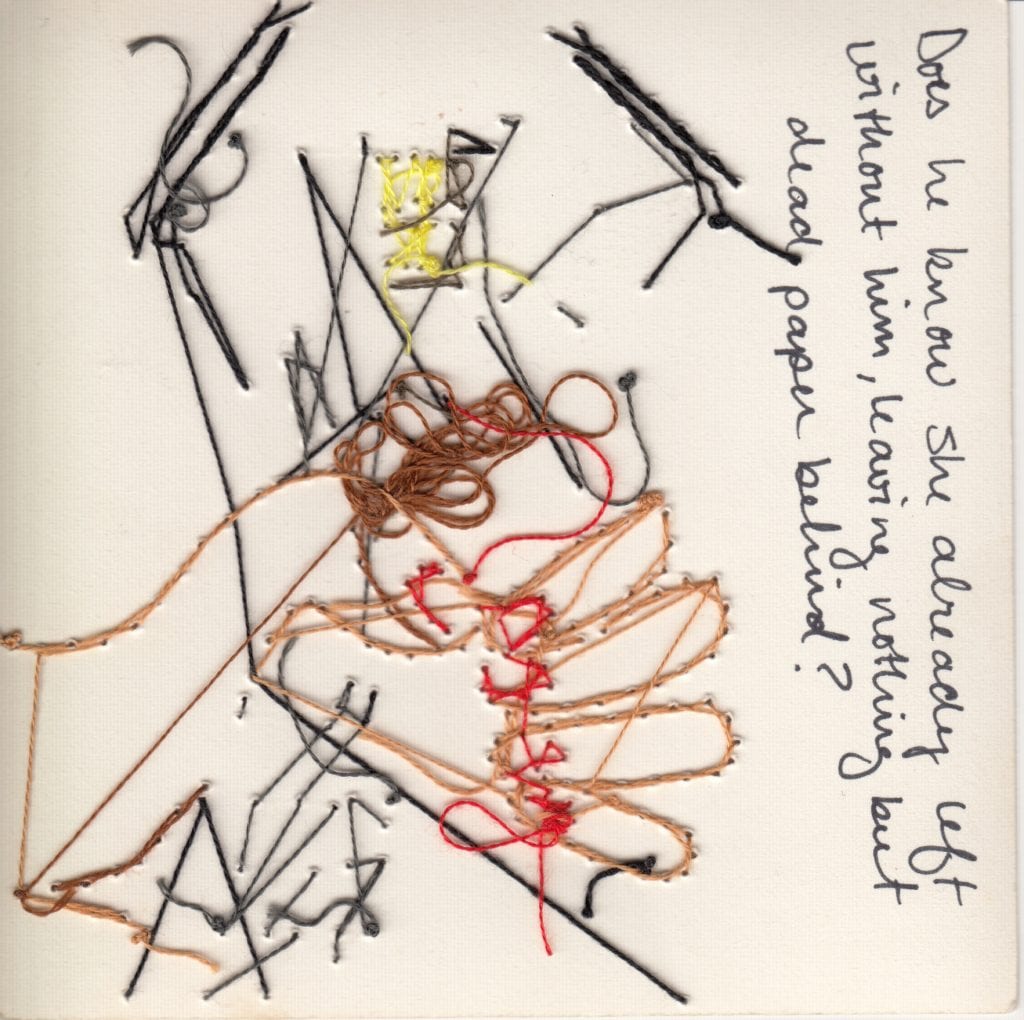

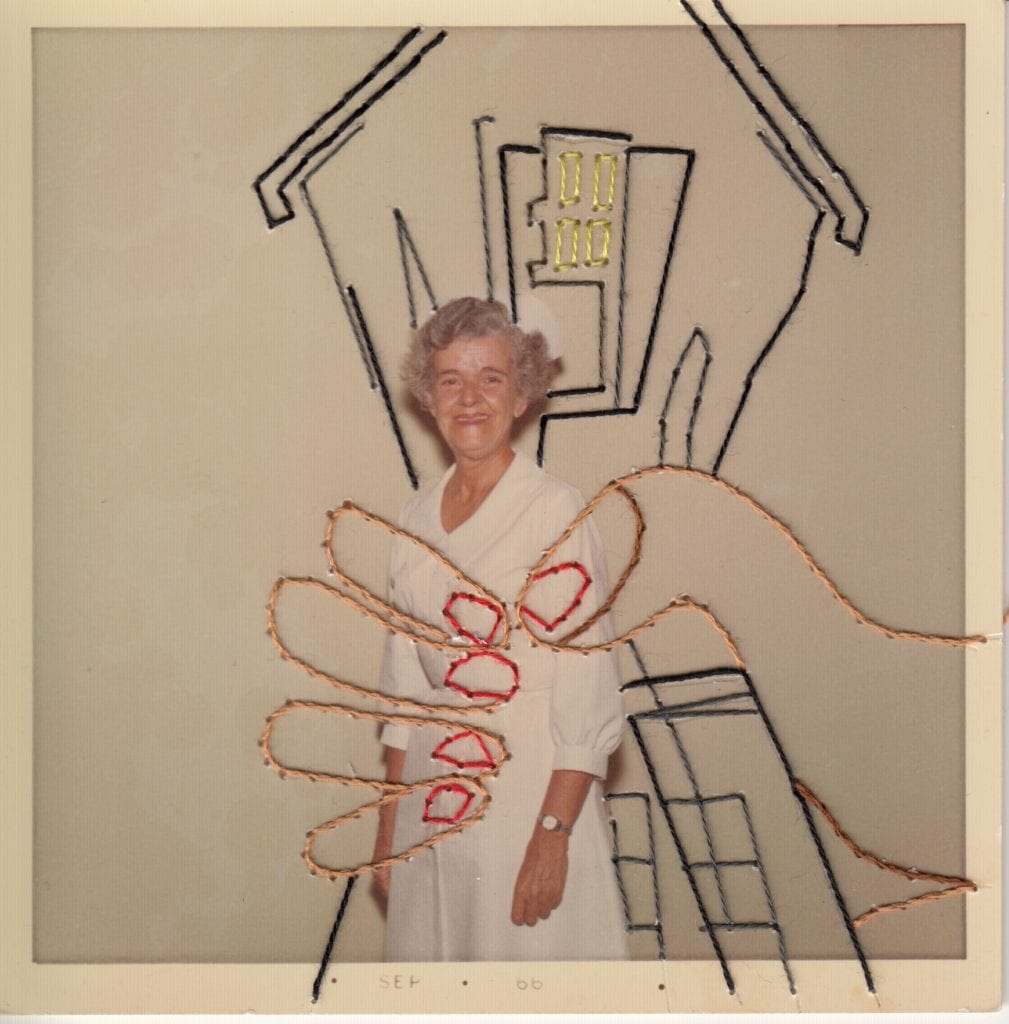

3) Art as self-authorization. That both of the angry, broken-hearted people listed above struggled with addiction issues all their lives, is the only thing not surprising to me.

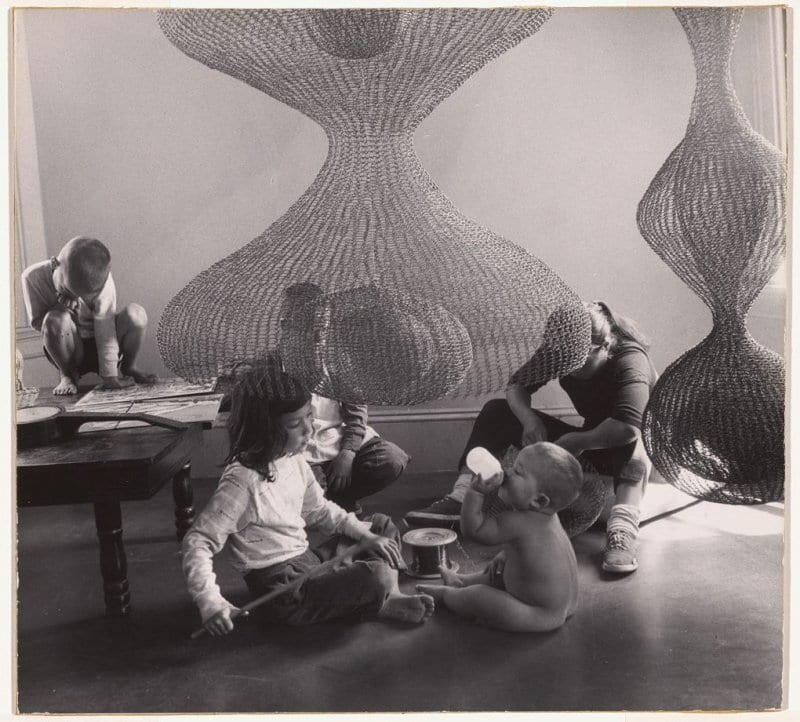

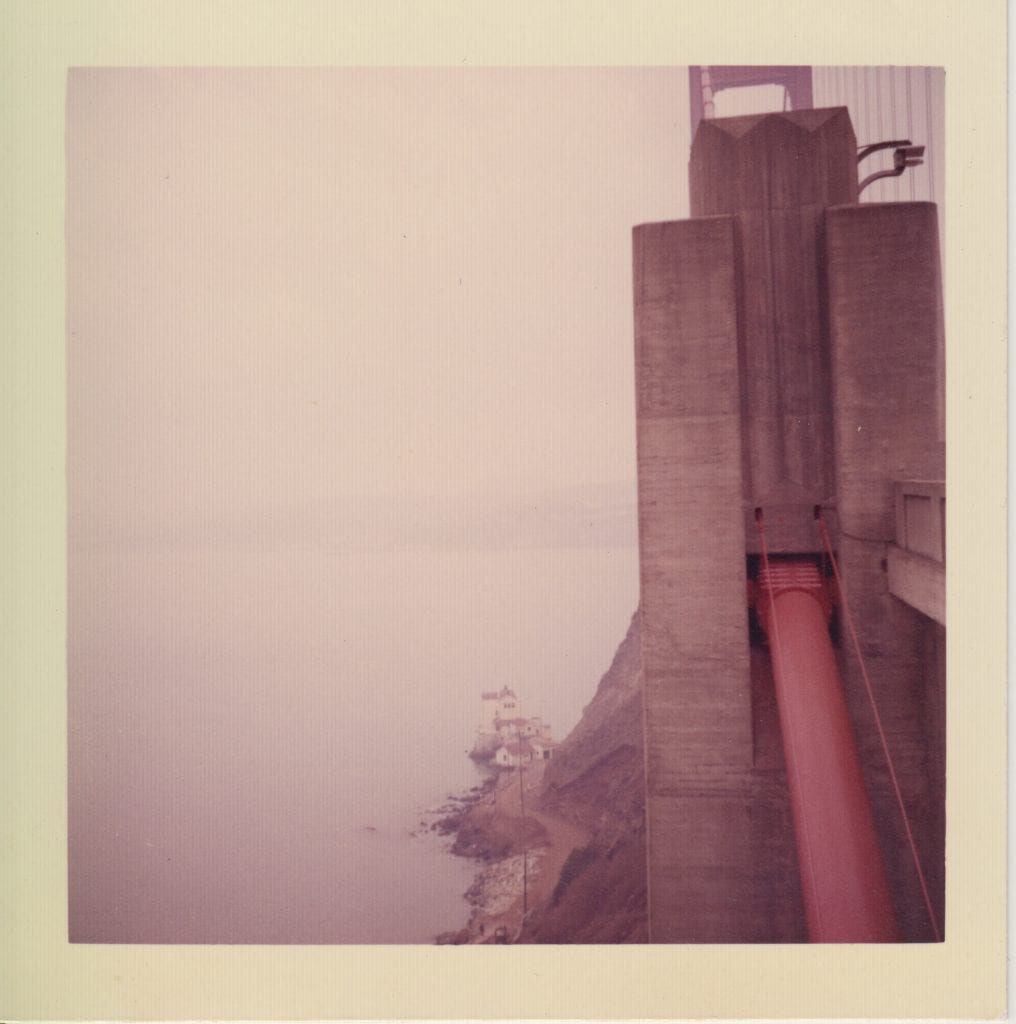

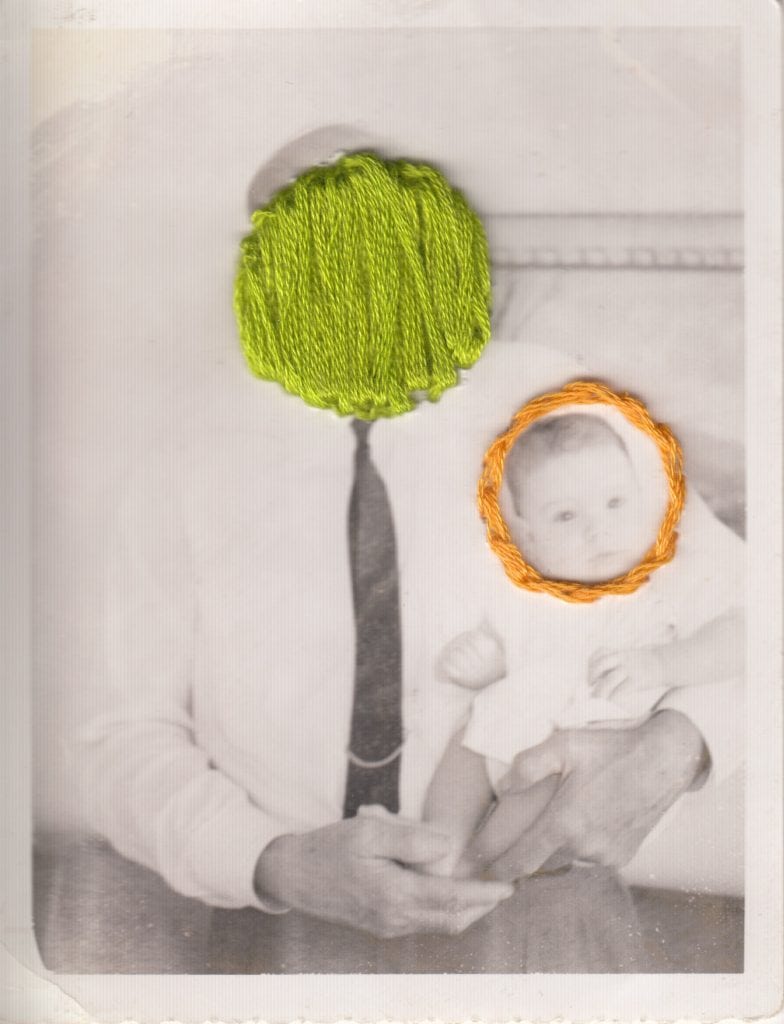

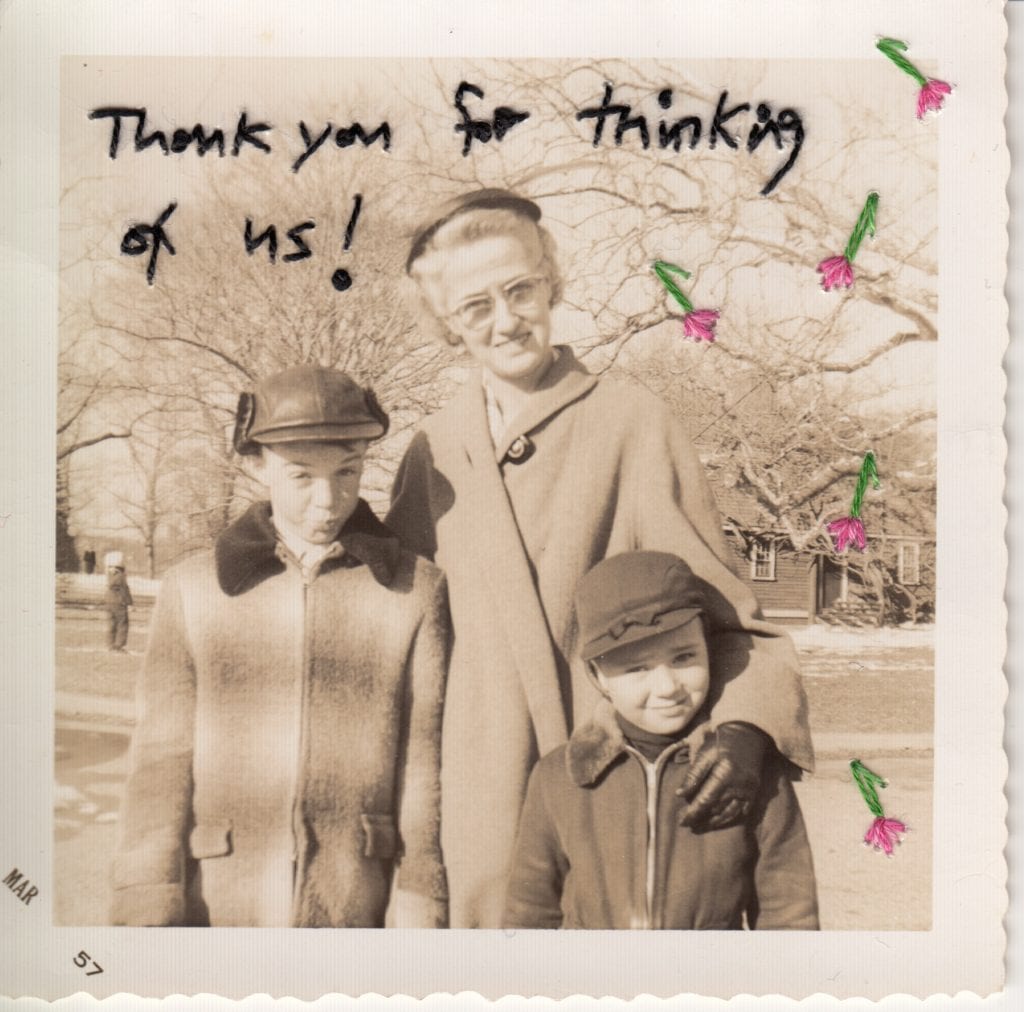

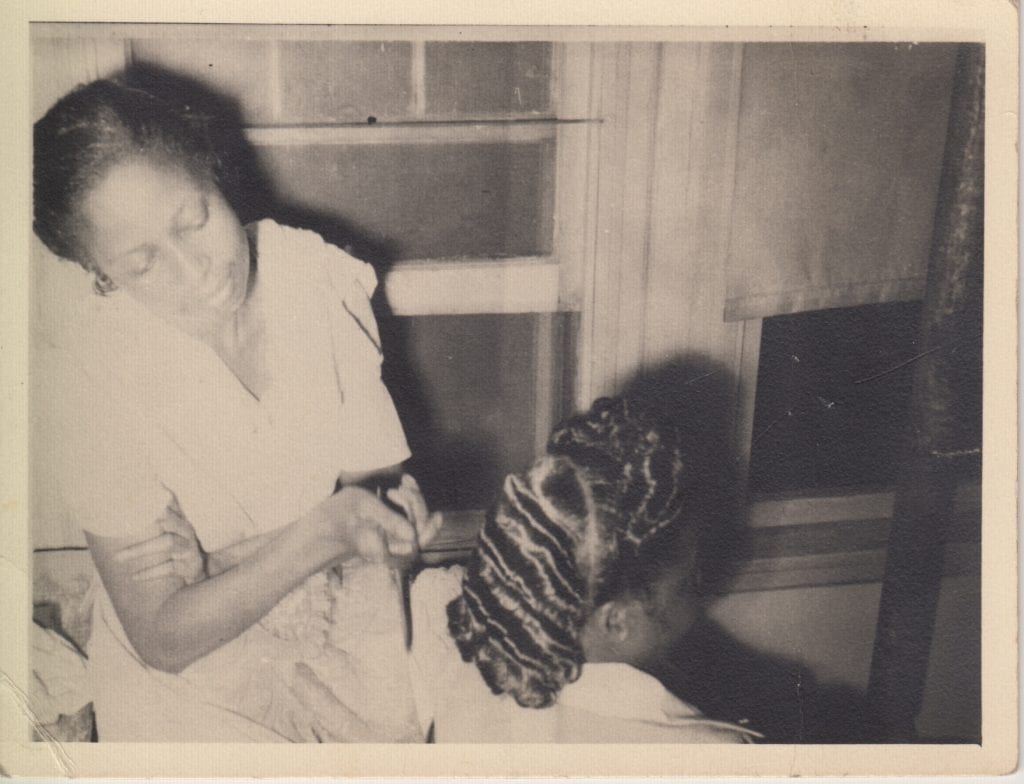

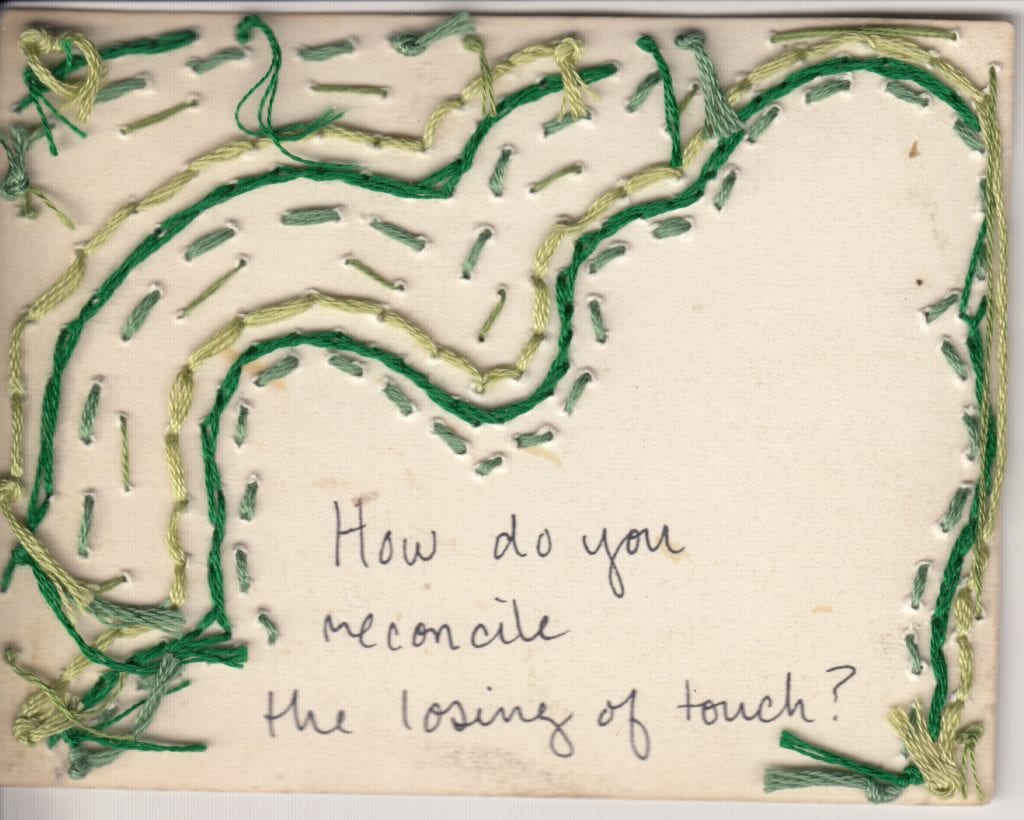

I’m interested in people who have channeled extraordinary pain into something else and then turned that “something else” into a brand new something else. Something only they could do or make or be. And if it’s got a little dash of rebellious, self-supporting stank on it, even better. Dennis Rodman became his own performance art piece on the basketball court after accepting that the love/loyalty he thought existed in the world did not, in fact, exist; turning into Dennis Rodman as we now know and (I) love him was the alternative to suicide. For Yates, writing about loneliness, hopelessness, and self-dishonesty the way he did throbs with recognition; this is someone who lived most of their life feeling like a balloon within a balloon, disconnected from others and bumbling about in the void.

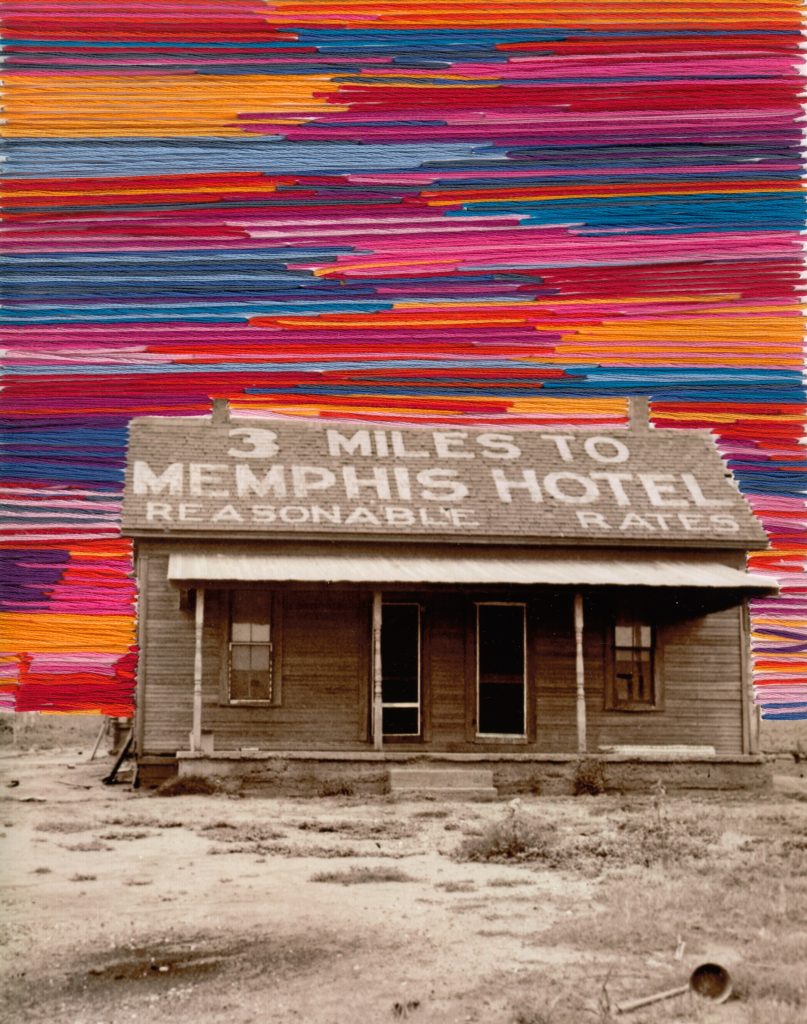

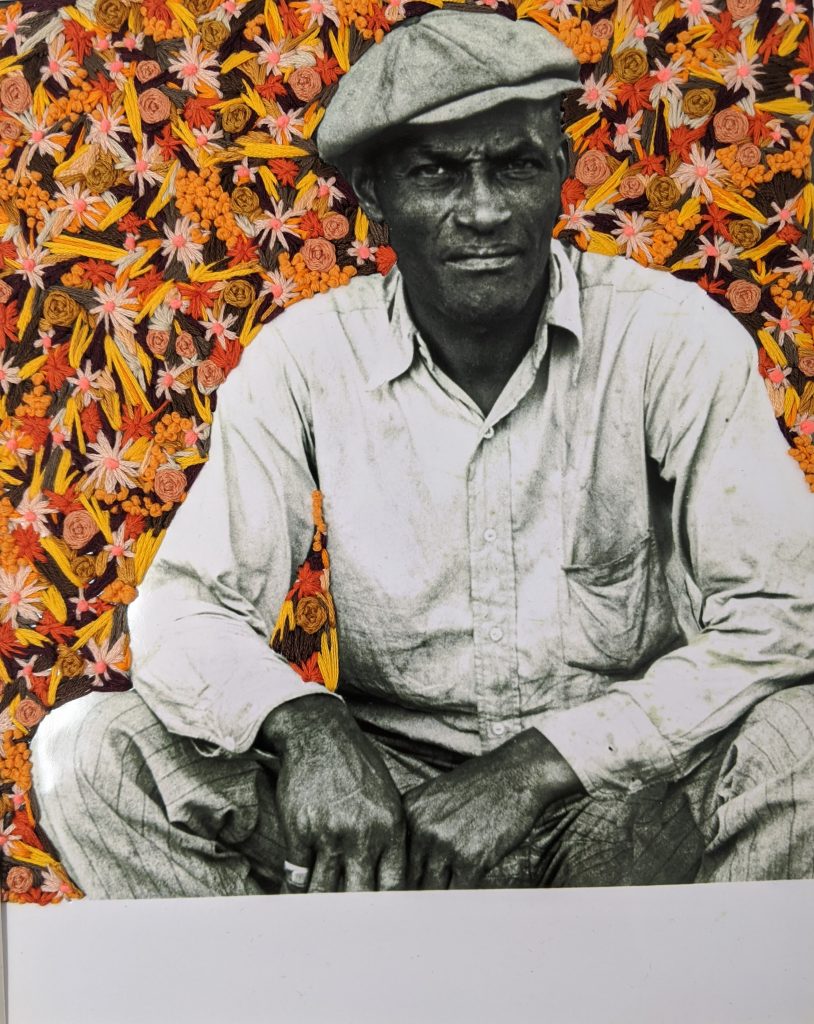

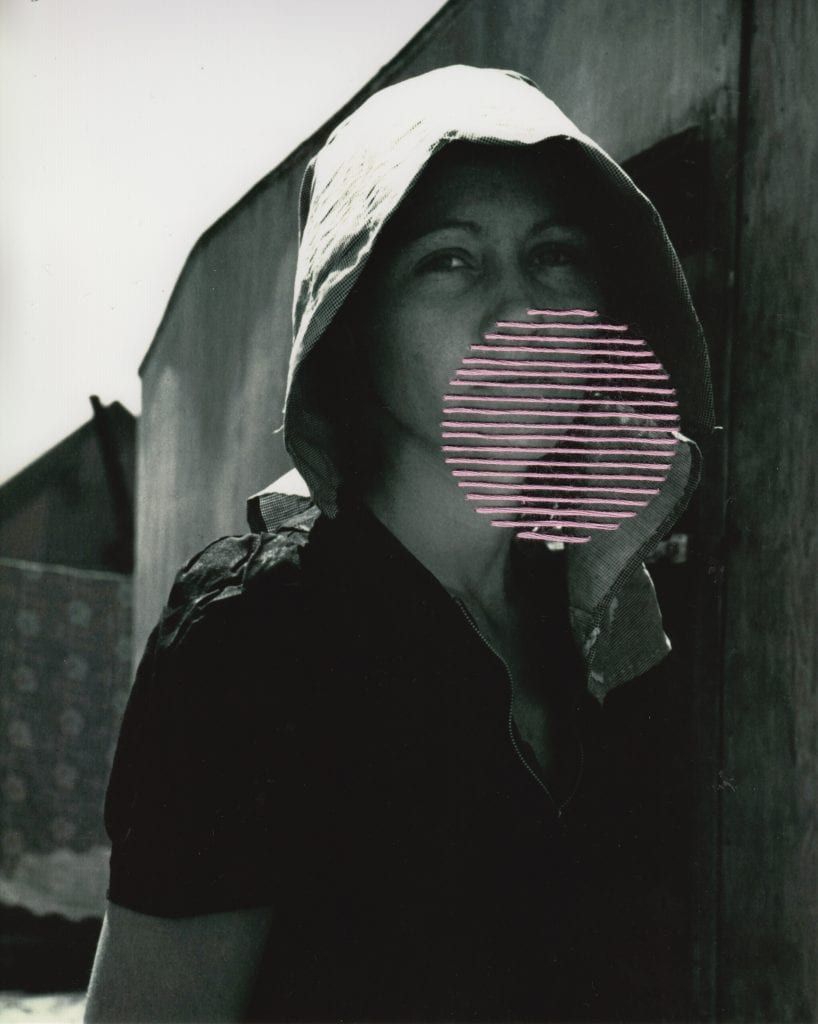

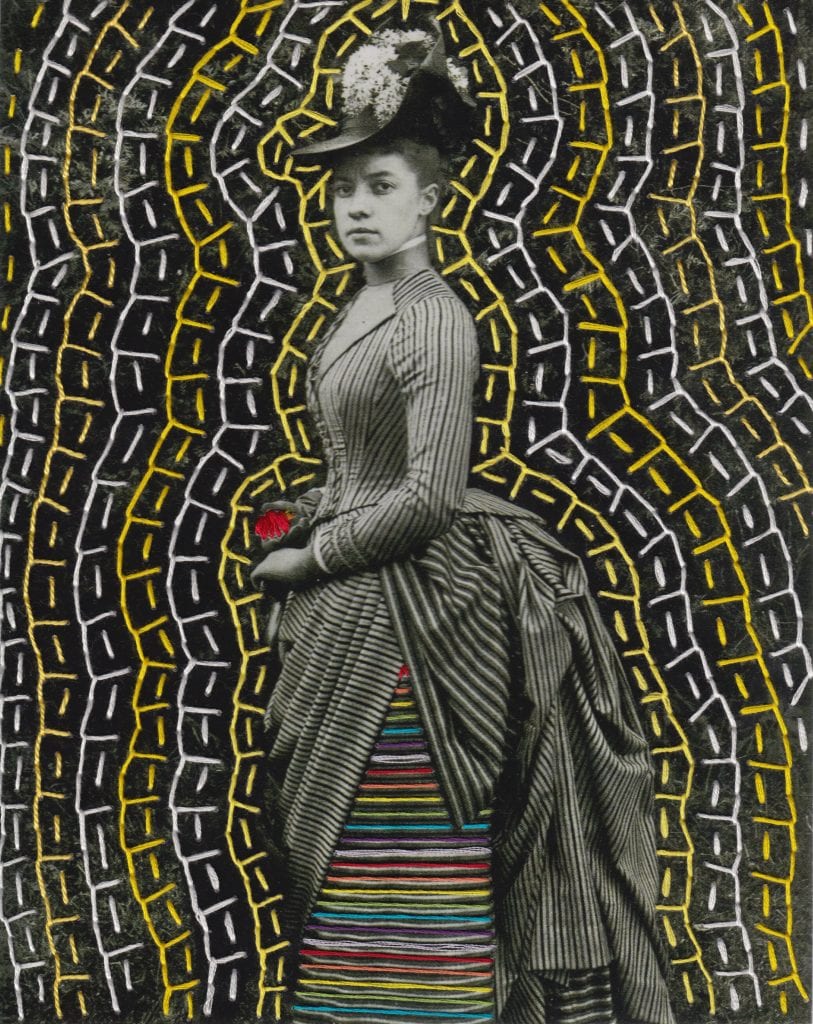

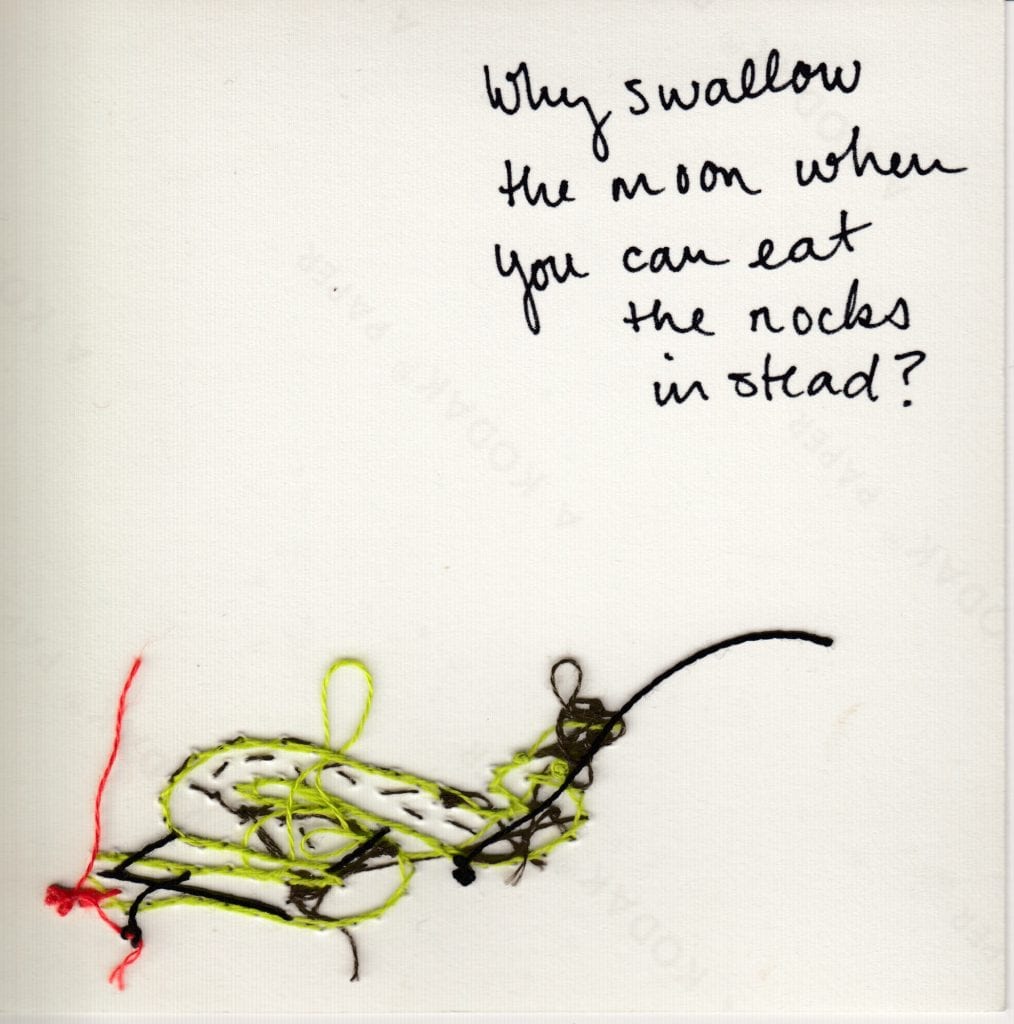

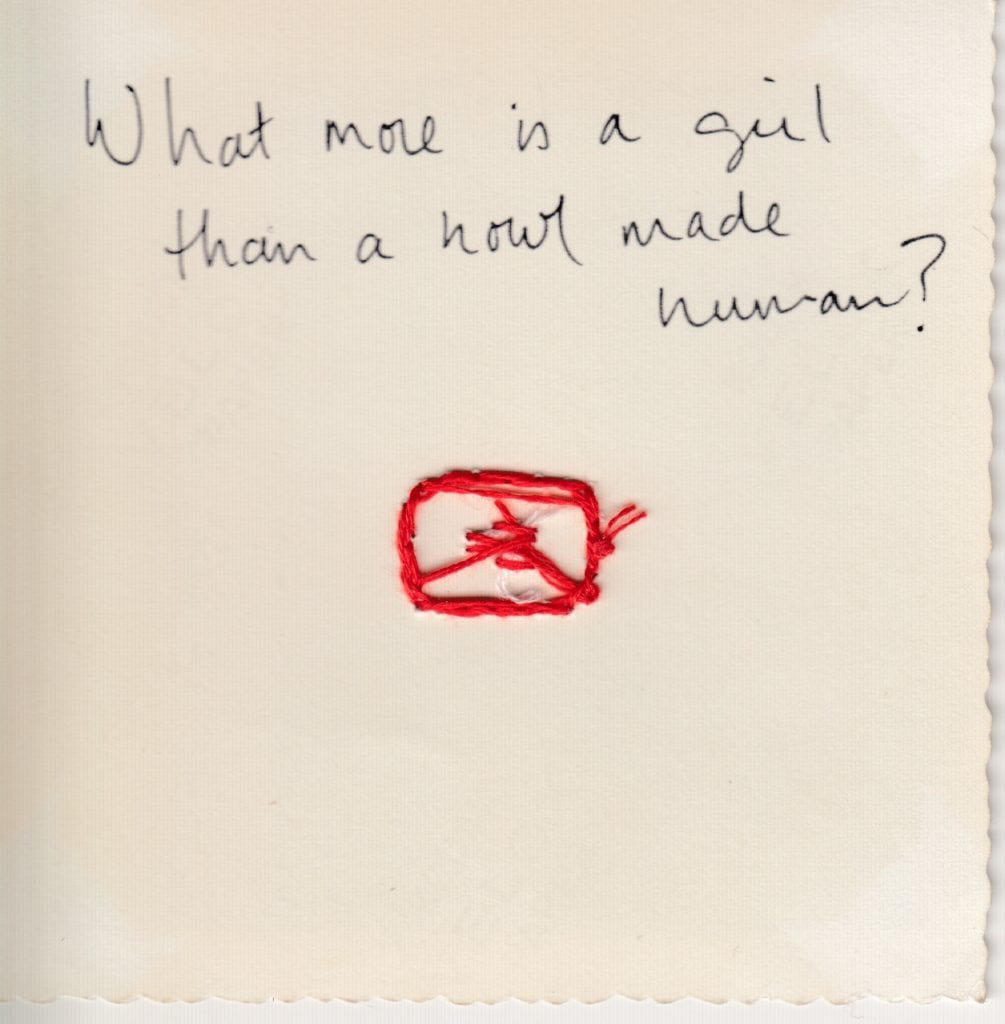

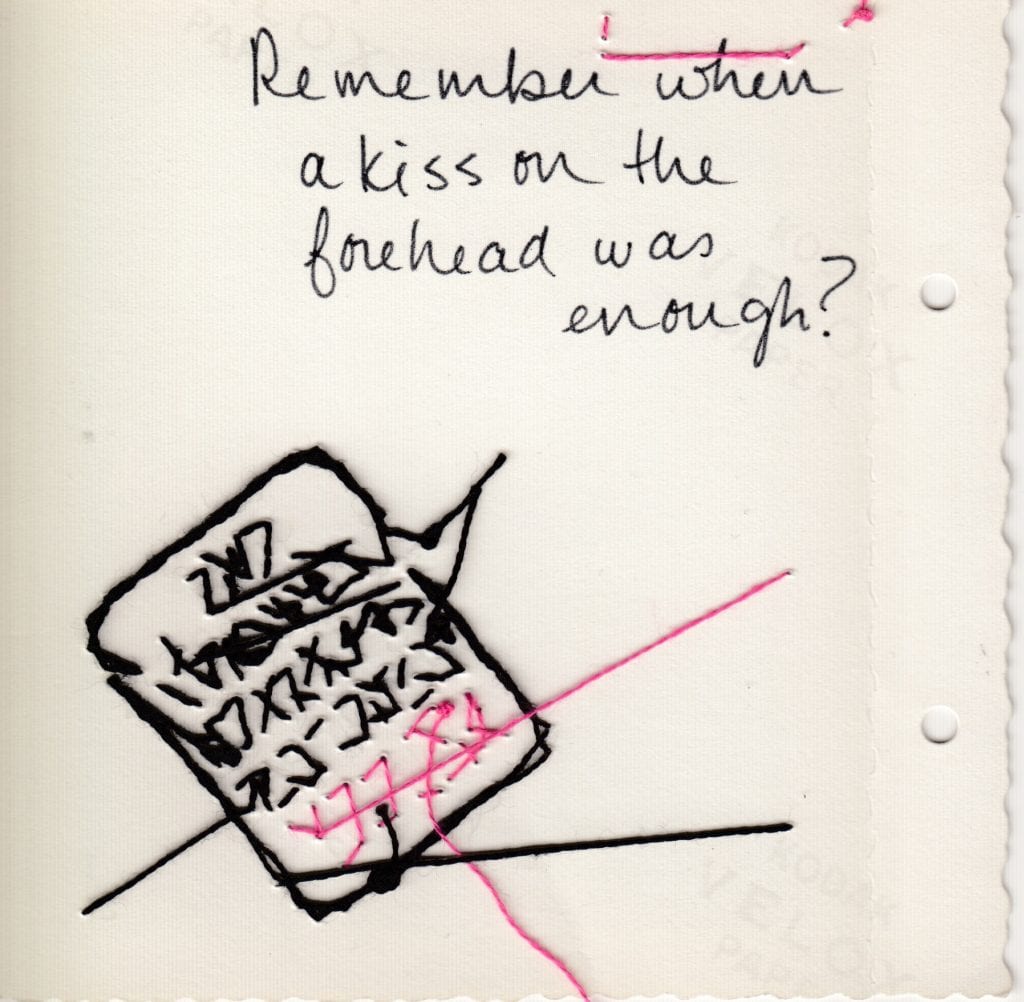

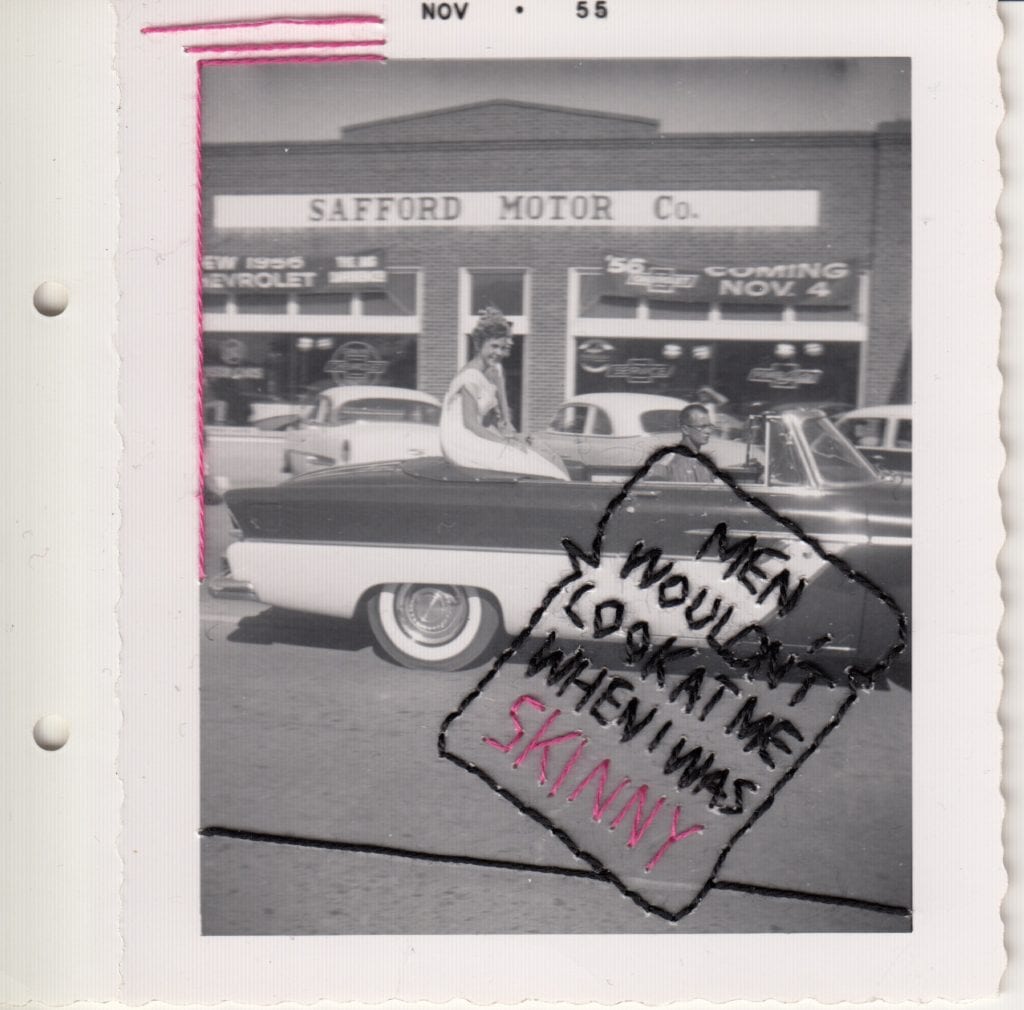

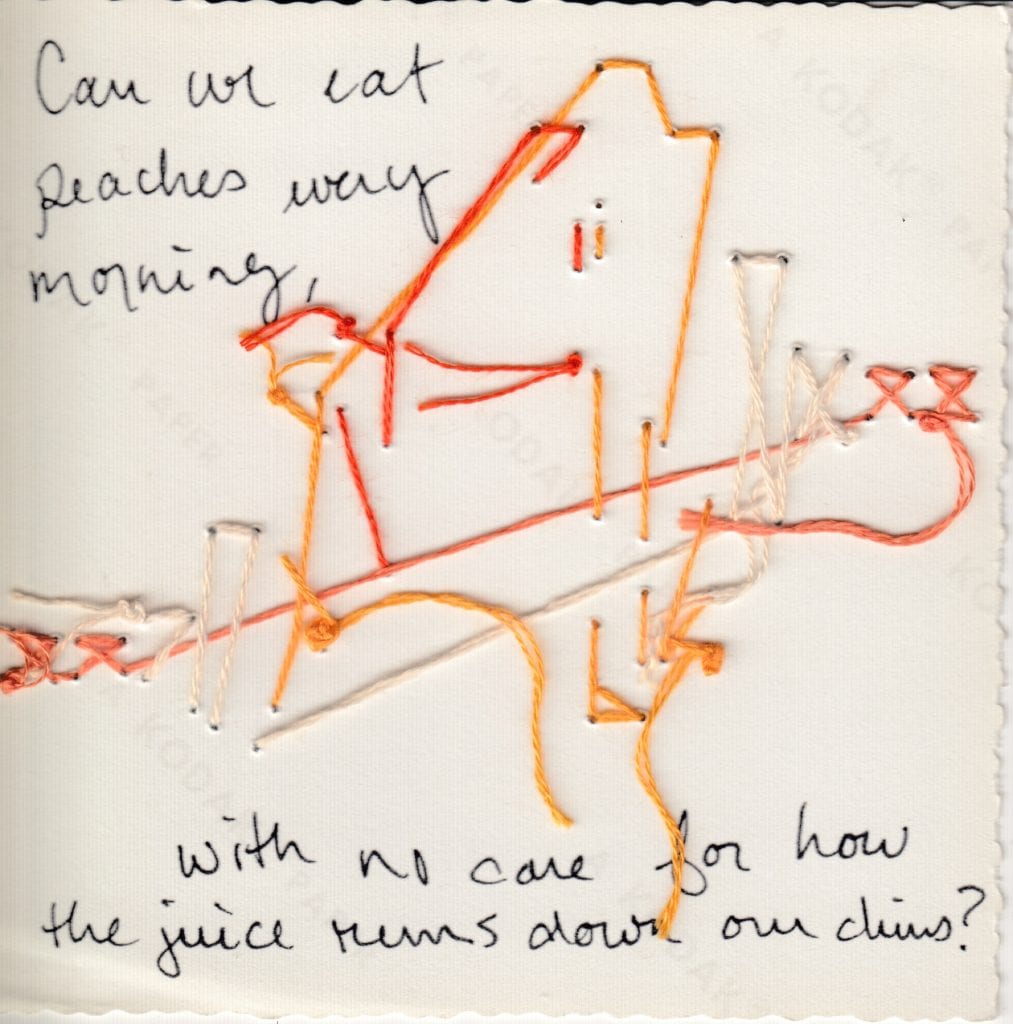

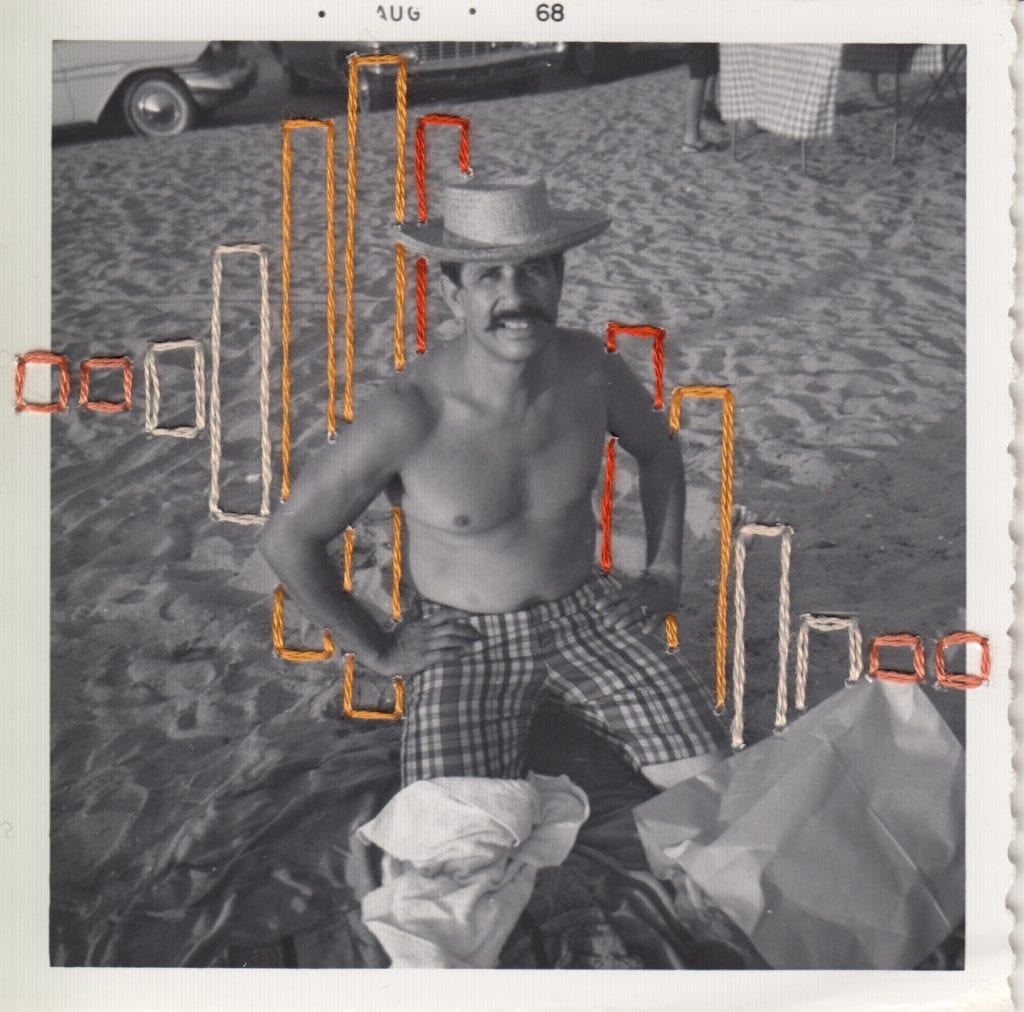

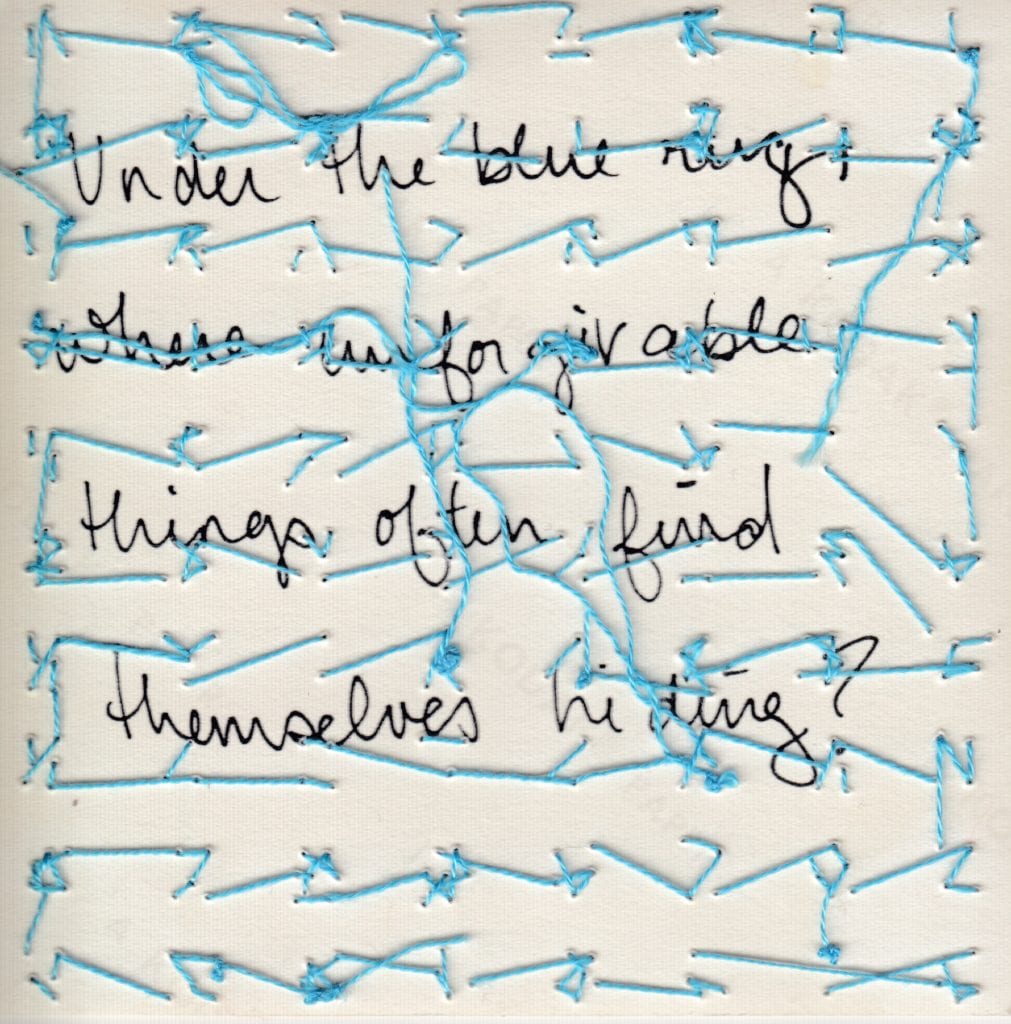

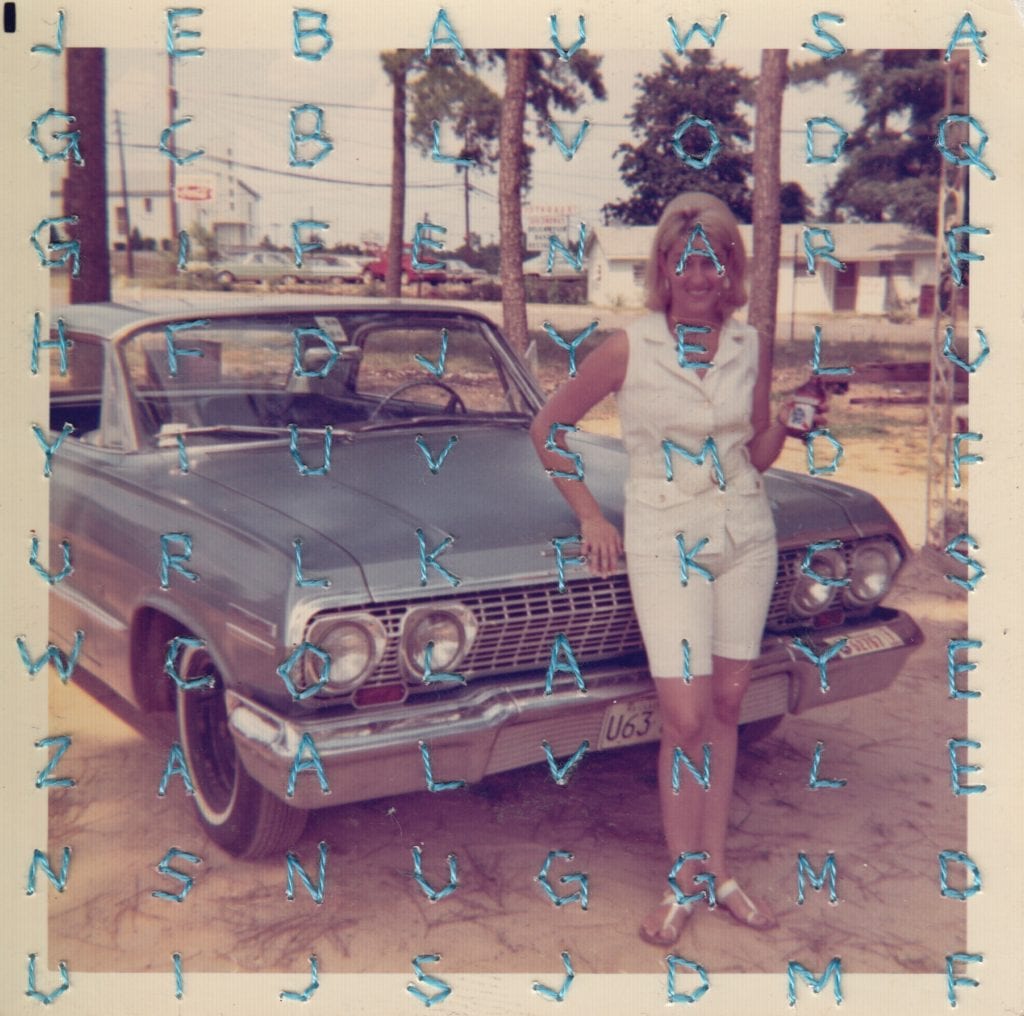

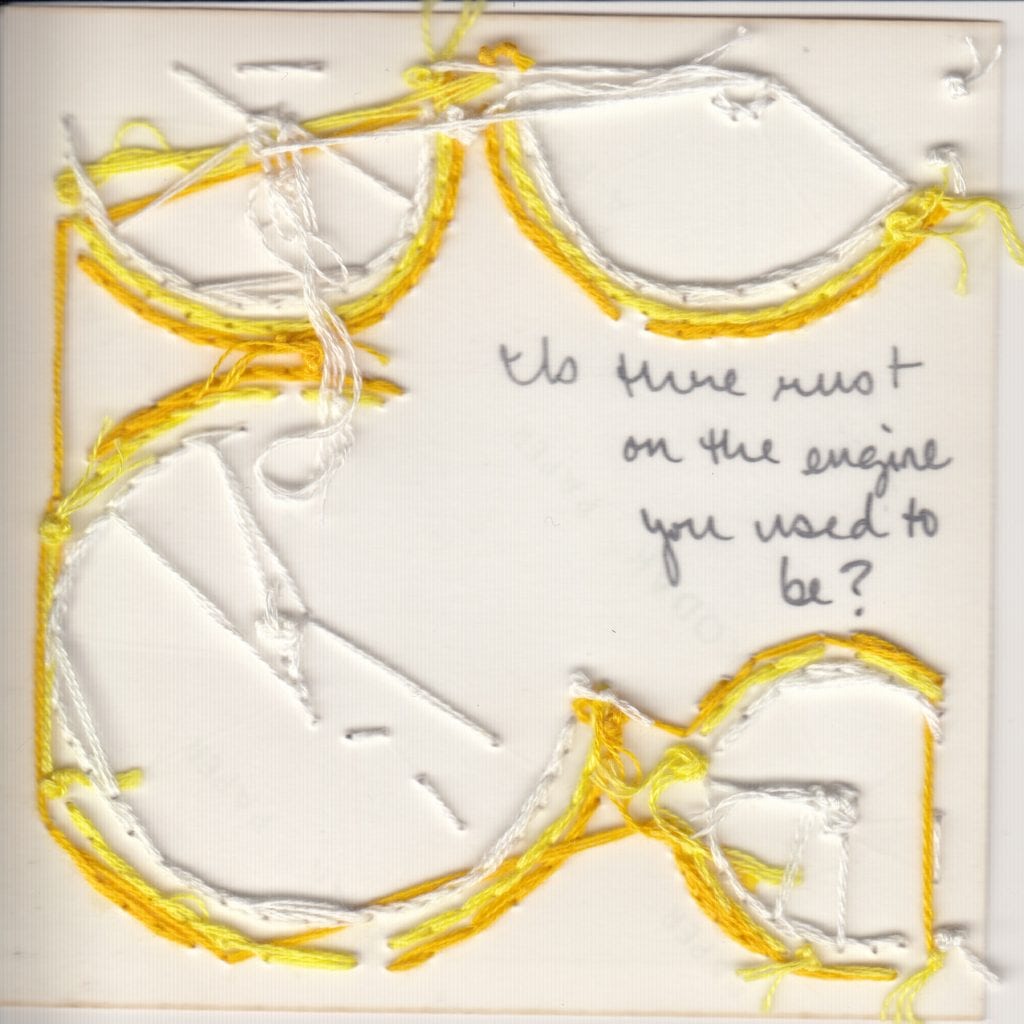

Maybe what’s appealing to me about Yates and Rodman right now relates to the third thing I thought about a lot this past month: the idea that being an artist is simply a matter of self-authorization—authorizing yourself to see what you see and express it however you see fit, then move on. I dig that. Feel inspired by it. Even when it comes from deeply flawed sources. Especially when it comes from deeply flawed sources (who have tried and failed to redeem themselves over and over). For those artists I am “rotten with sentimentality.”

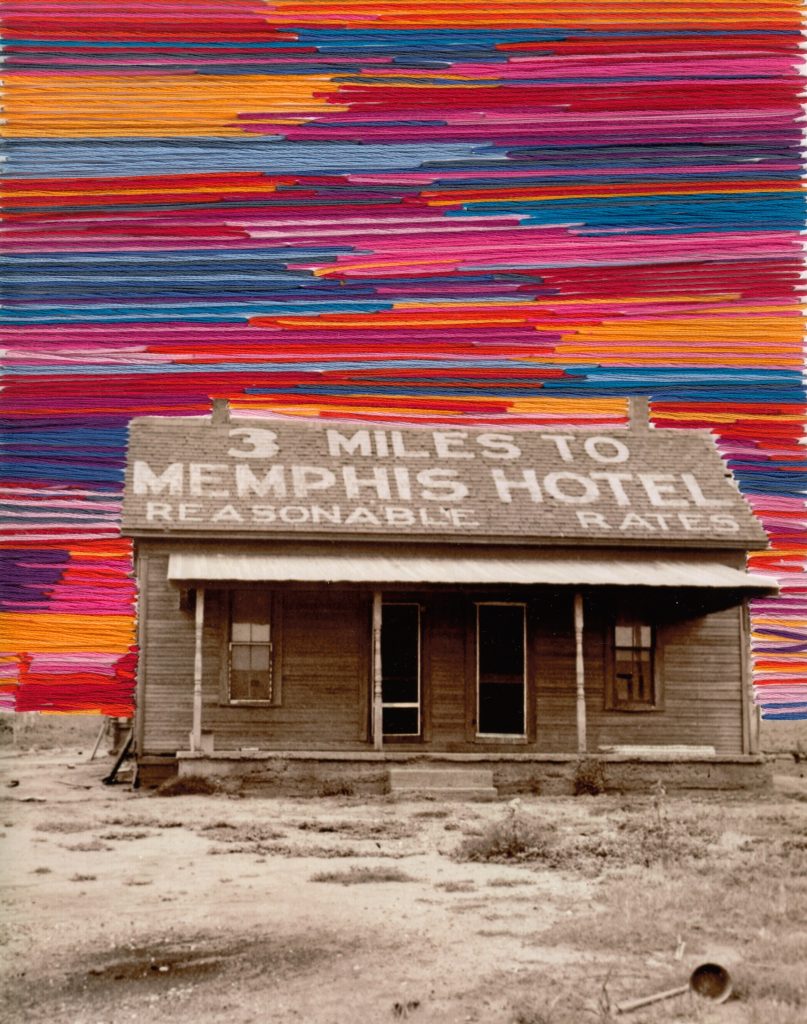

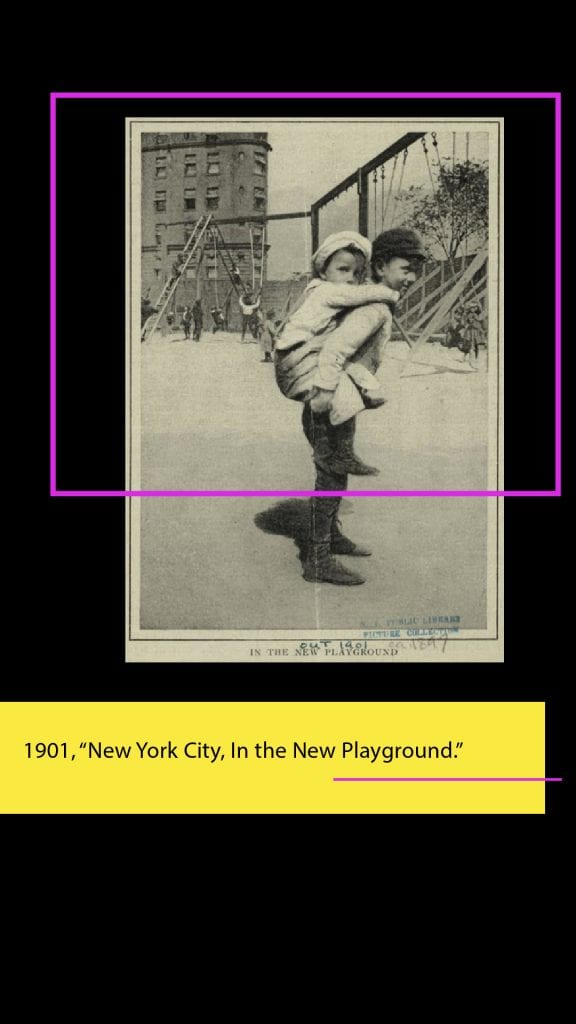

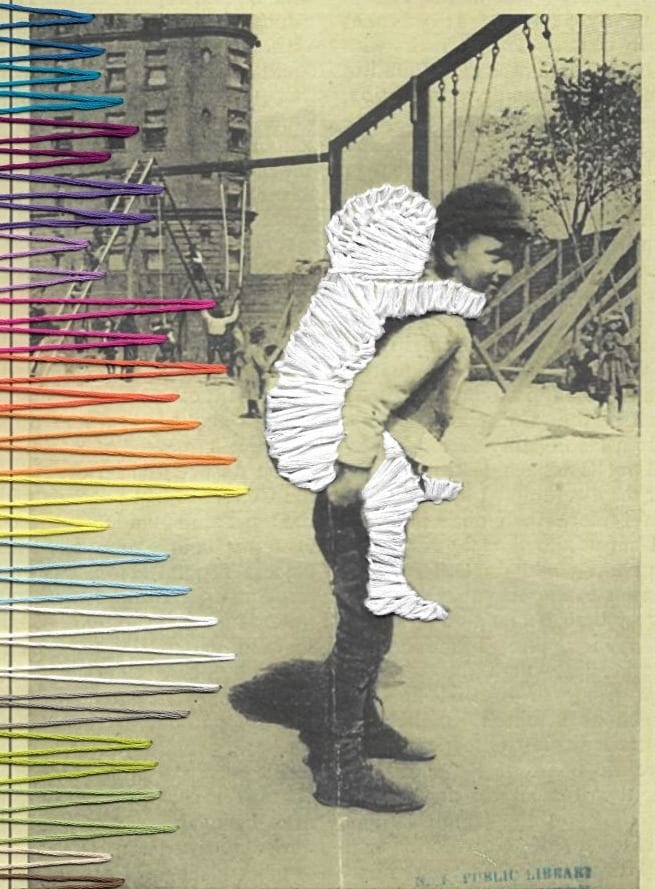

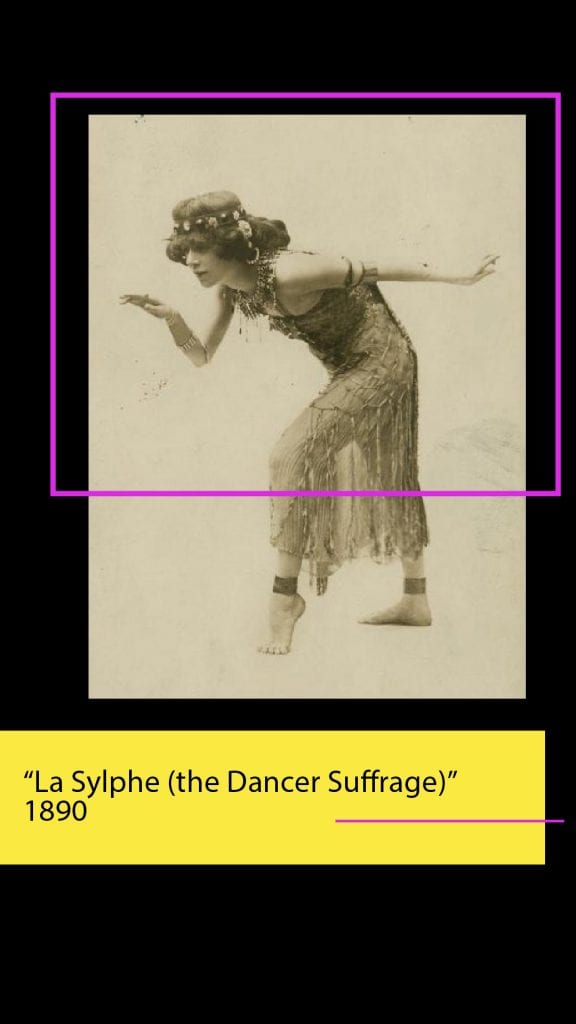

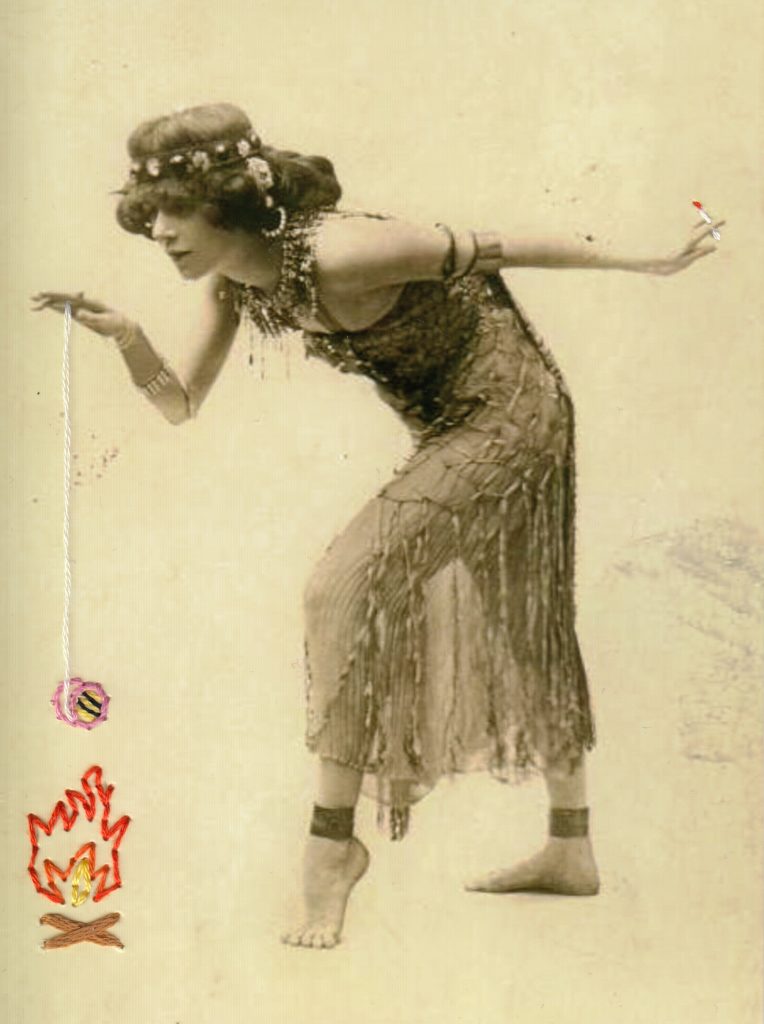

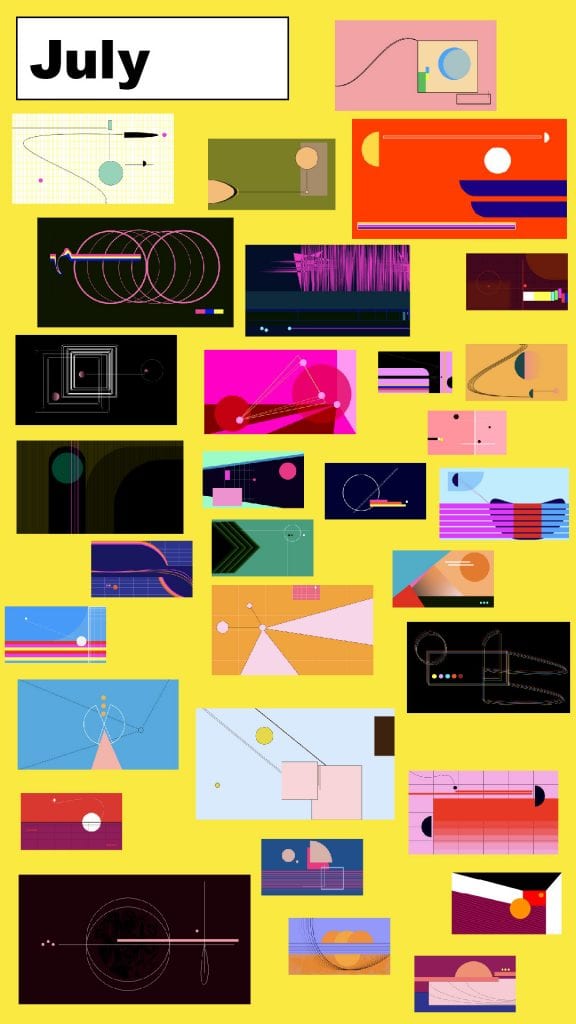

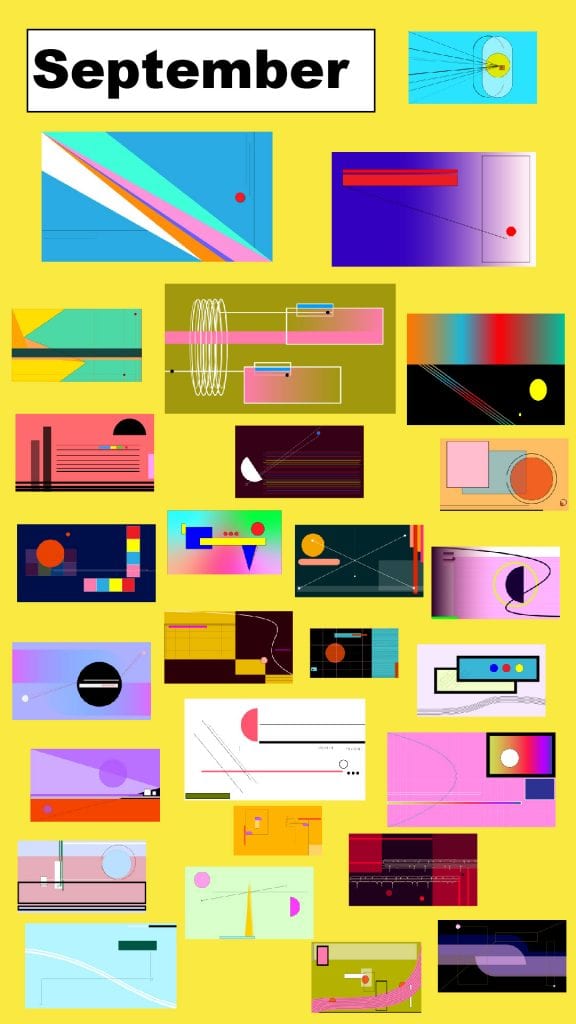

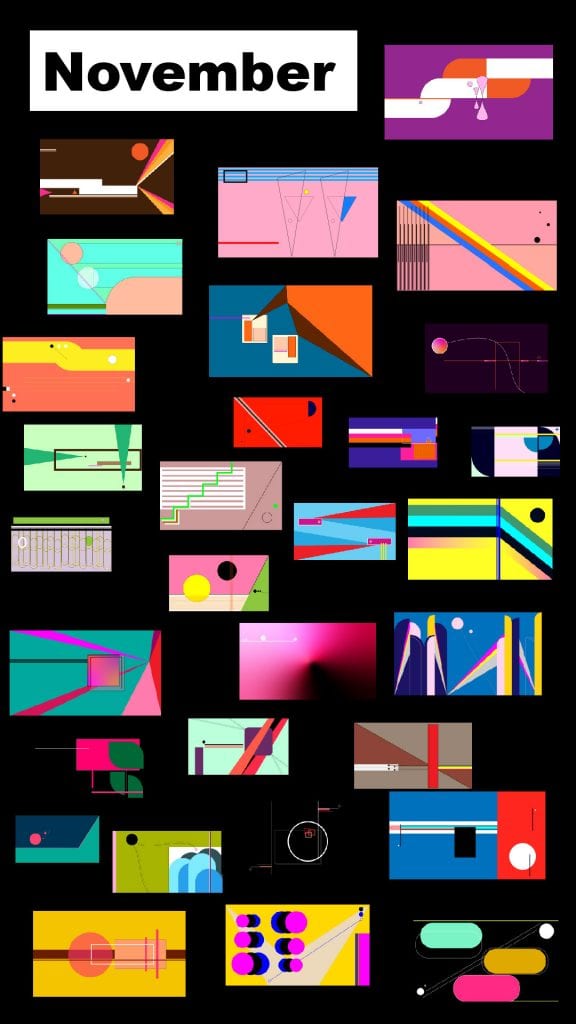

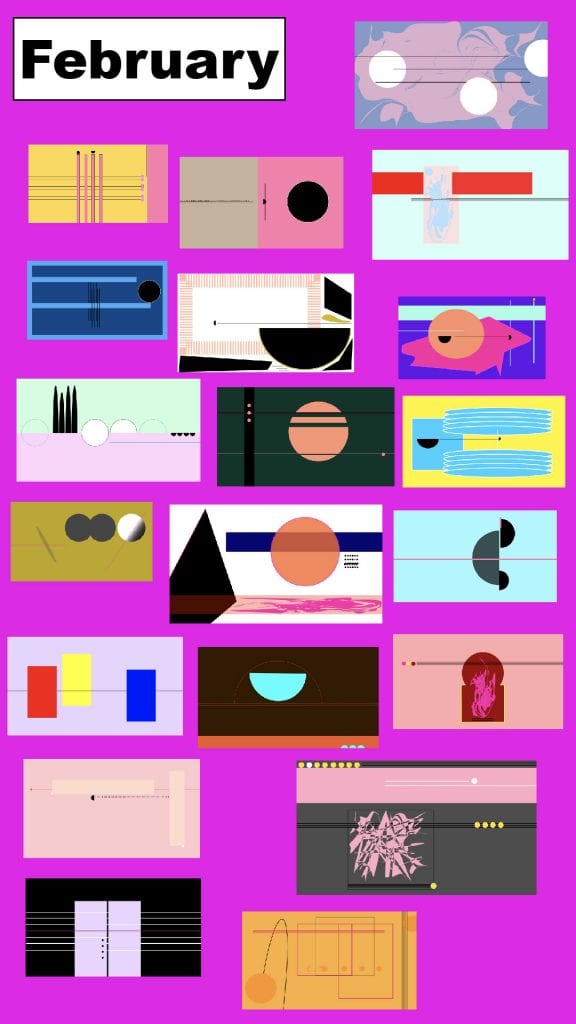

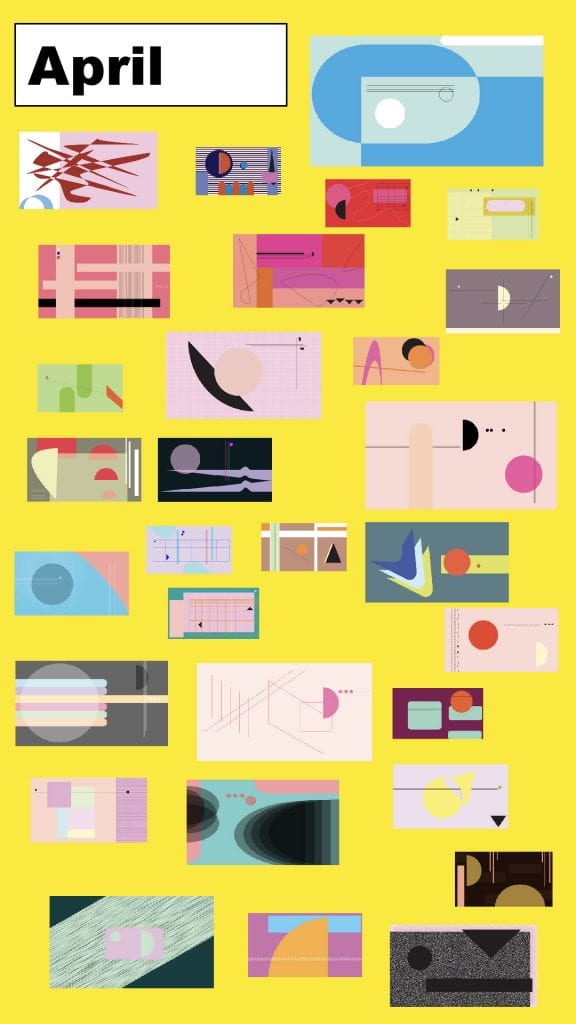

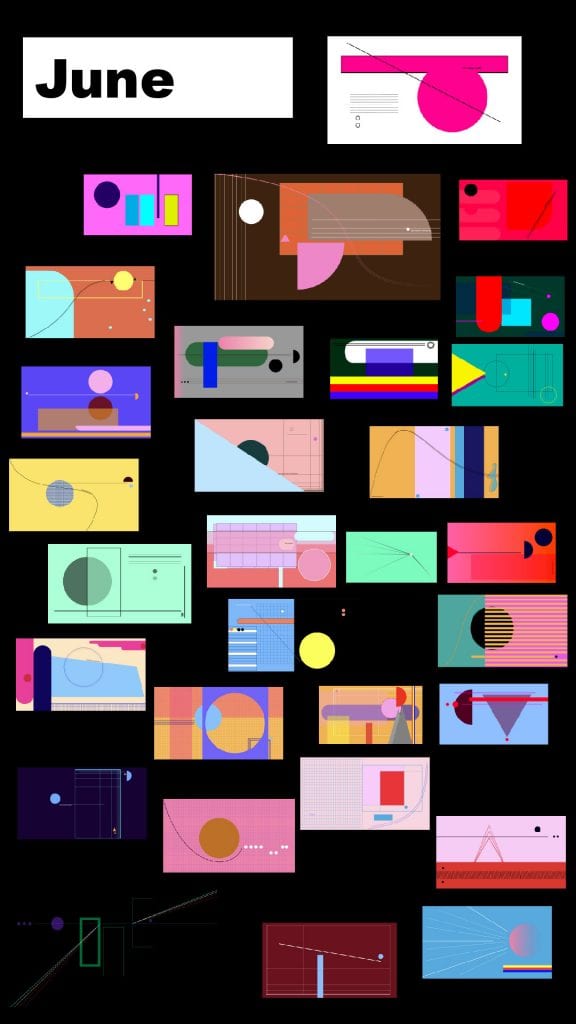

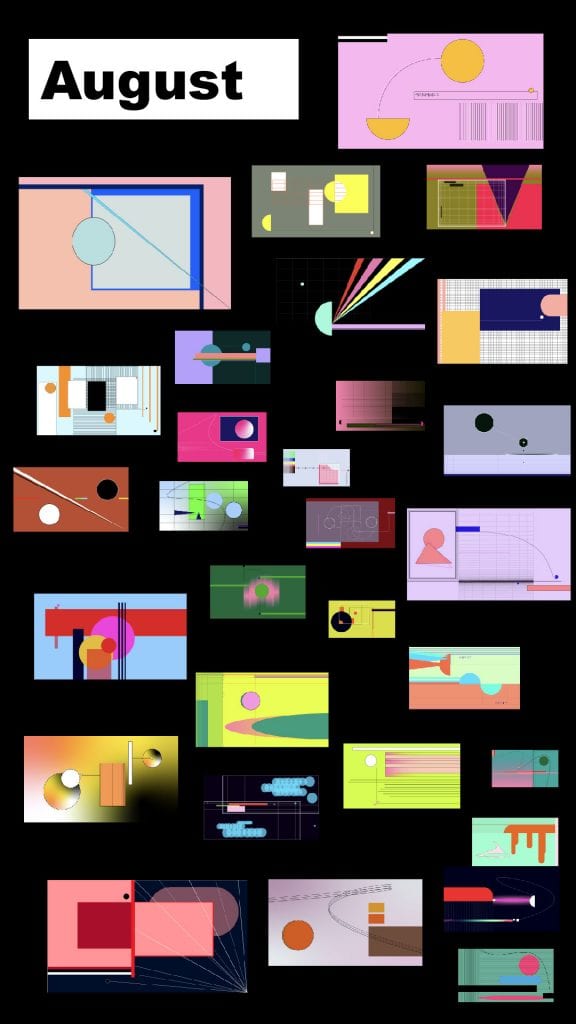

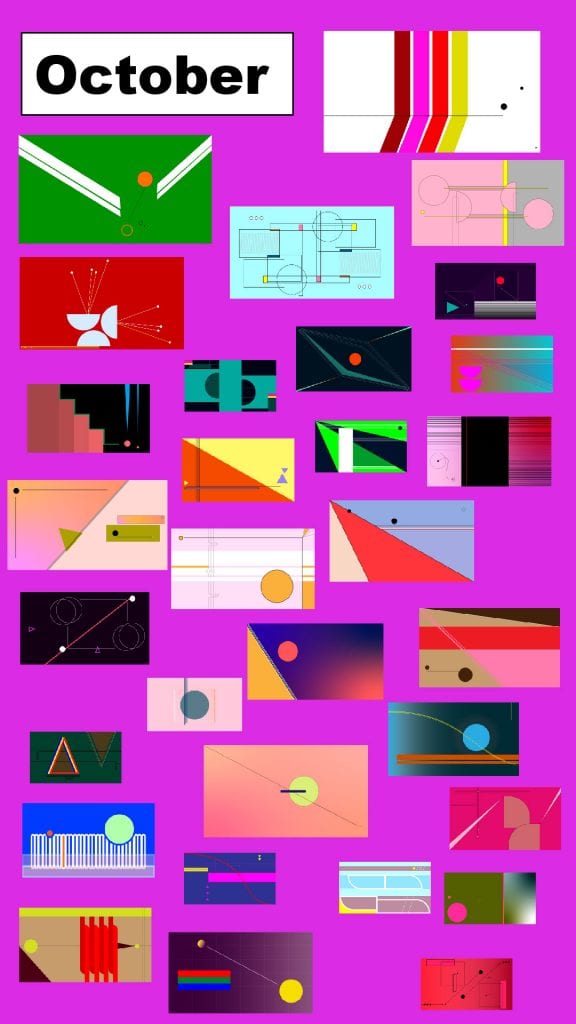

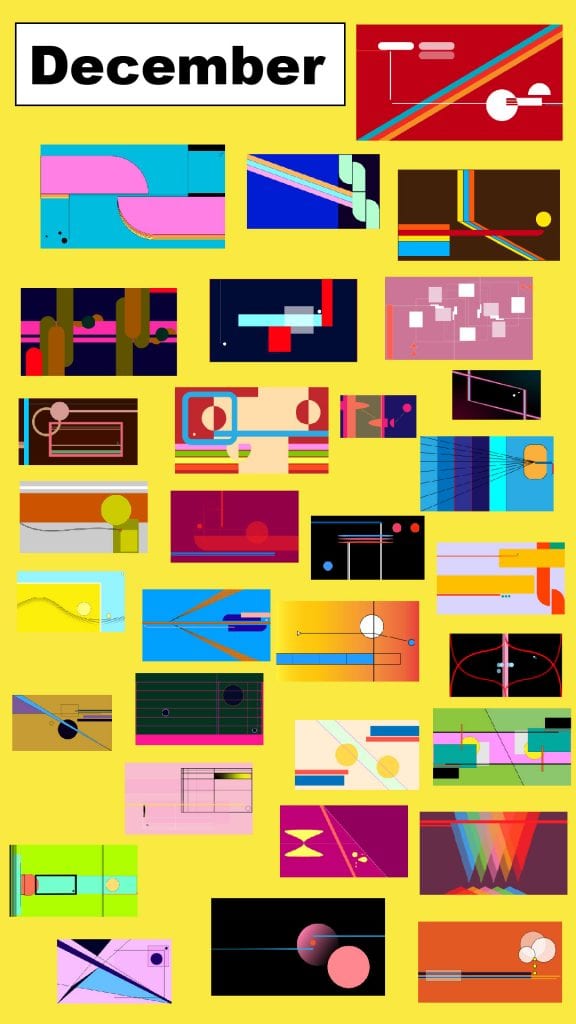

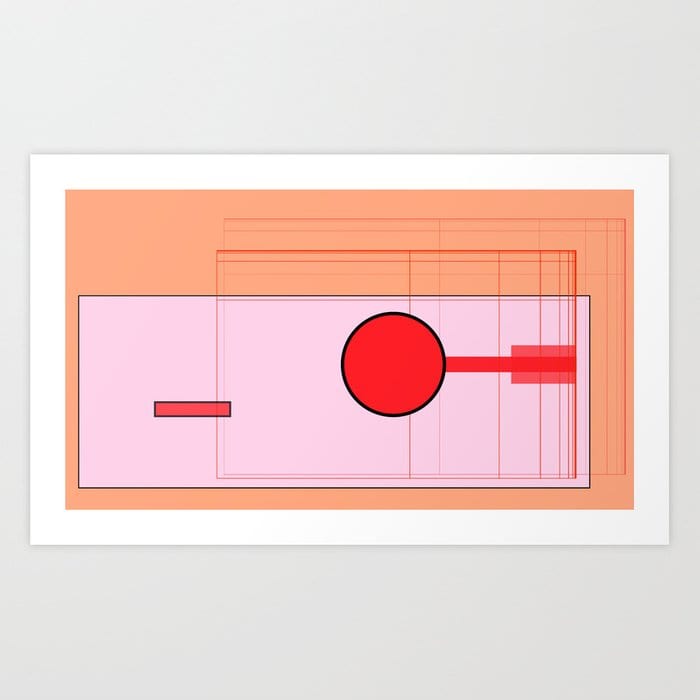

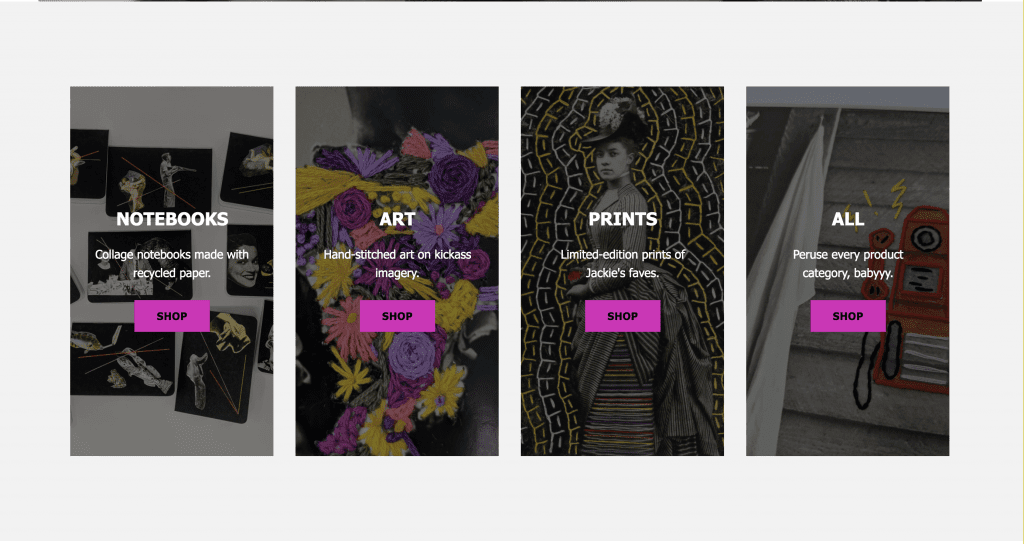

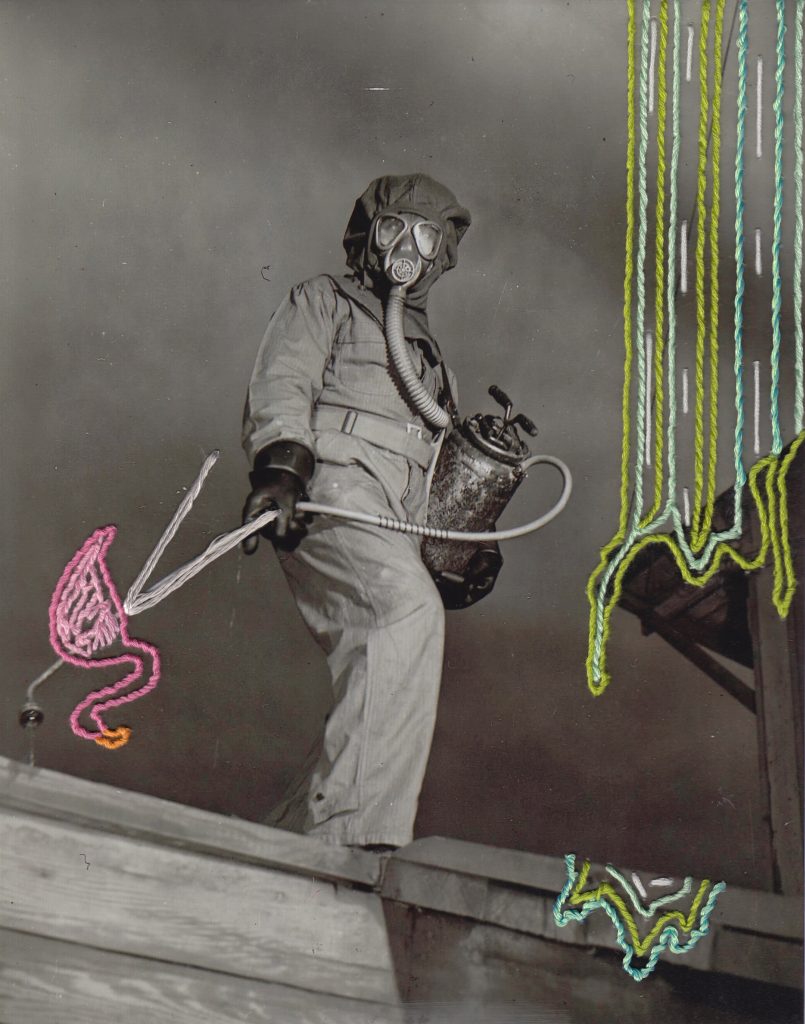

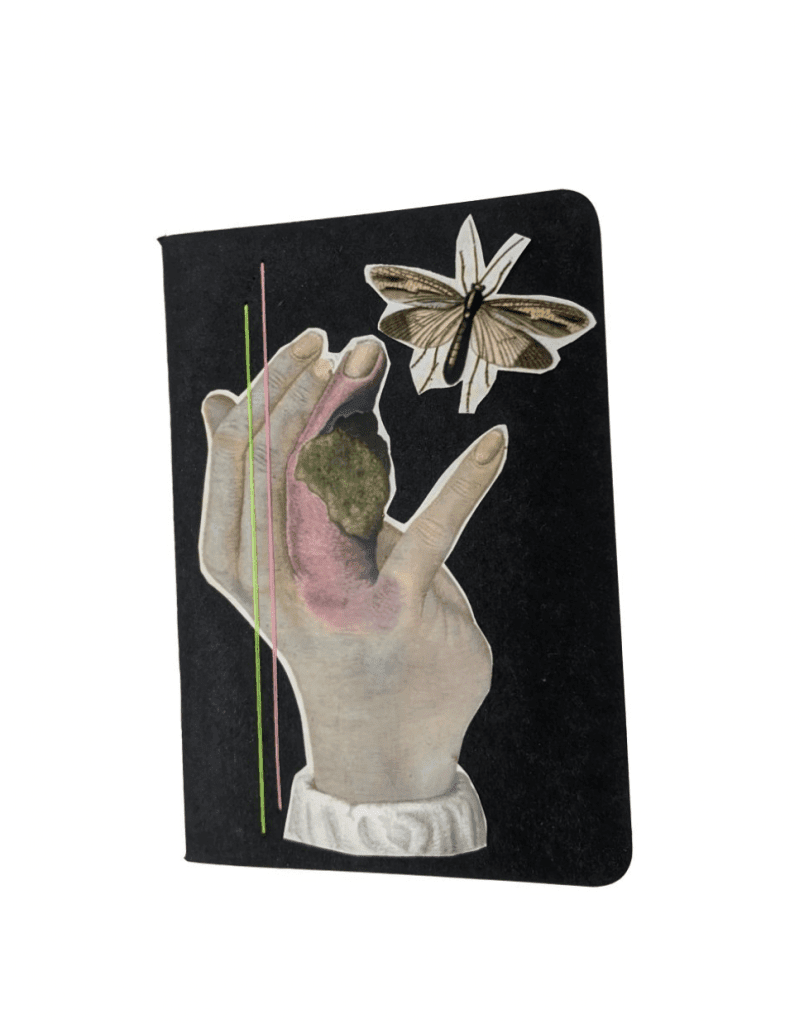

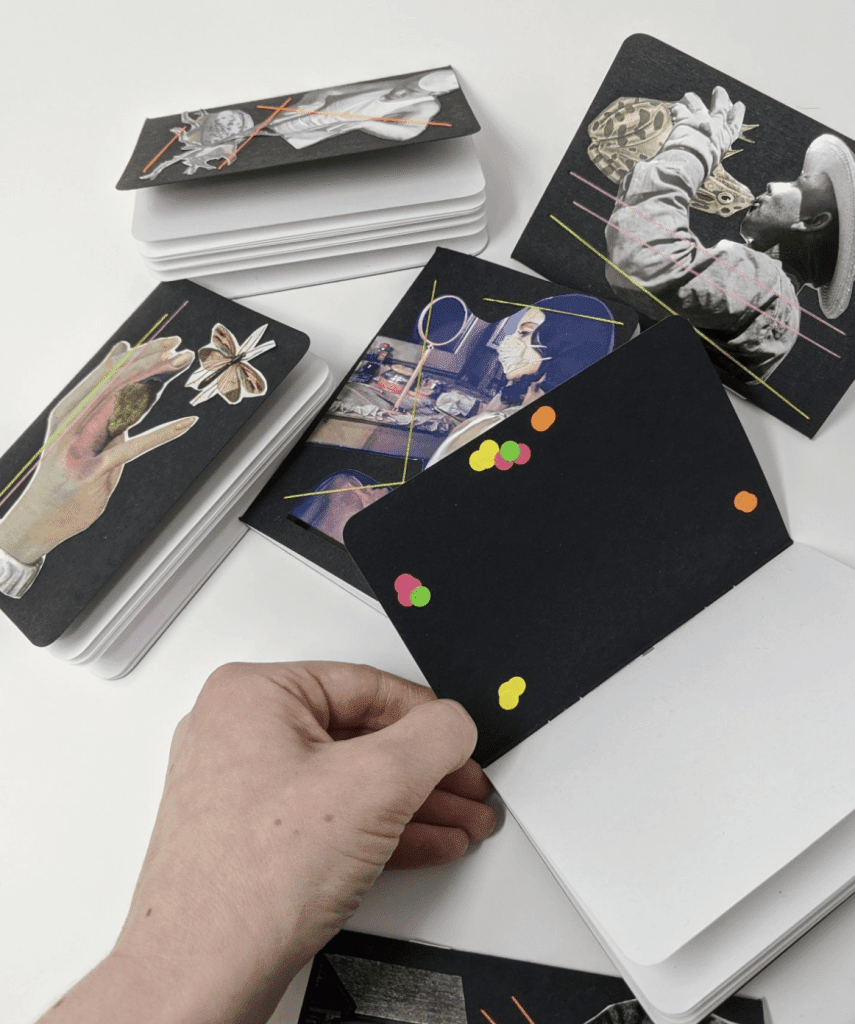

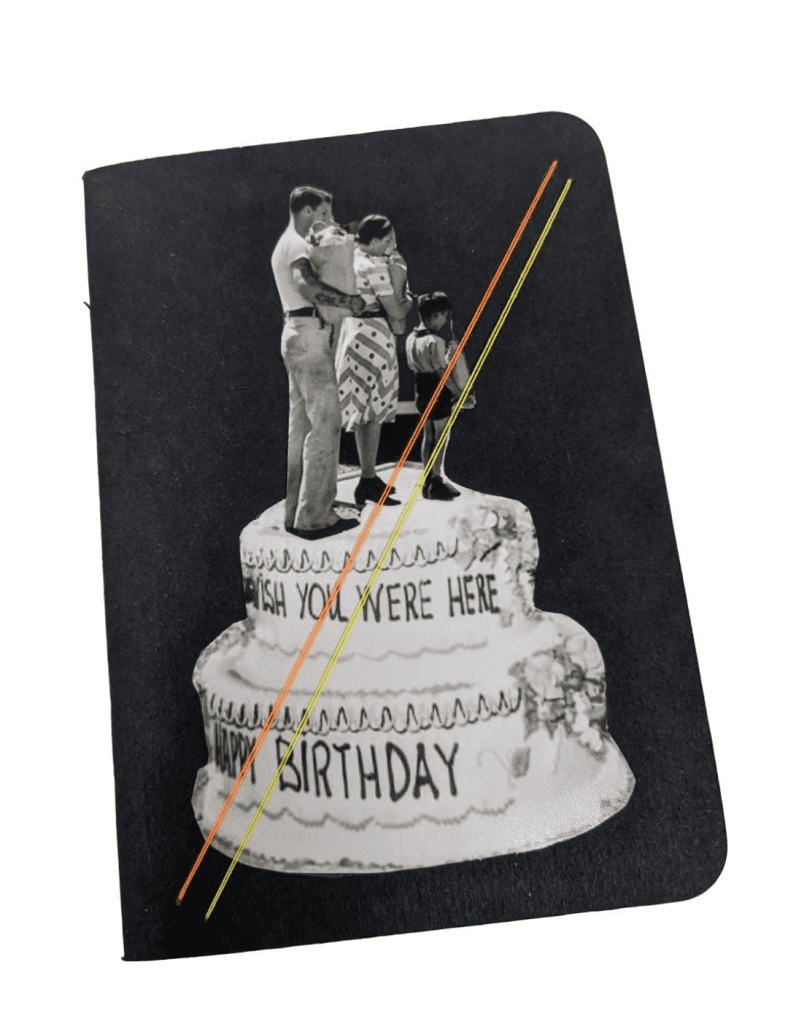

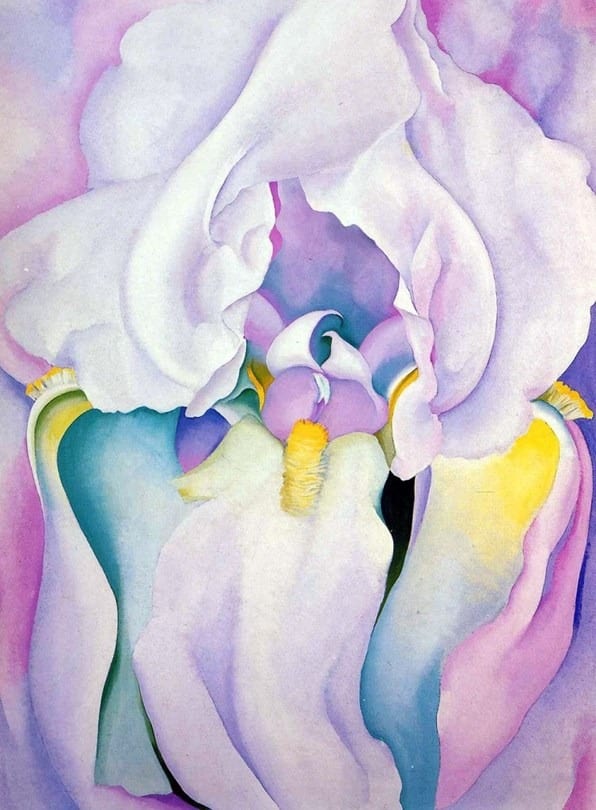

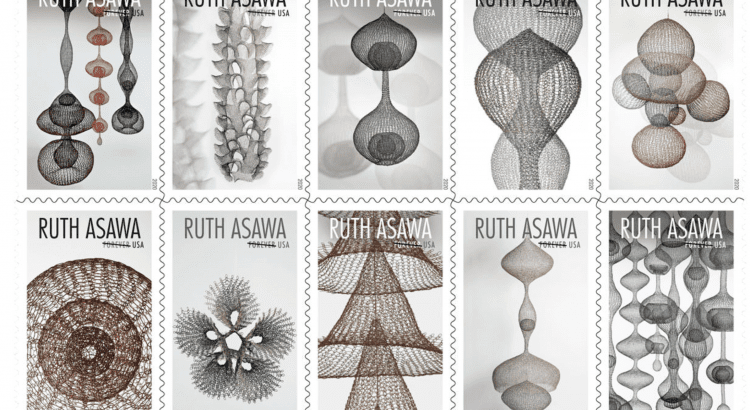

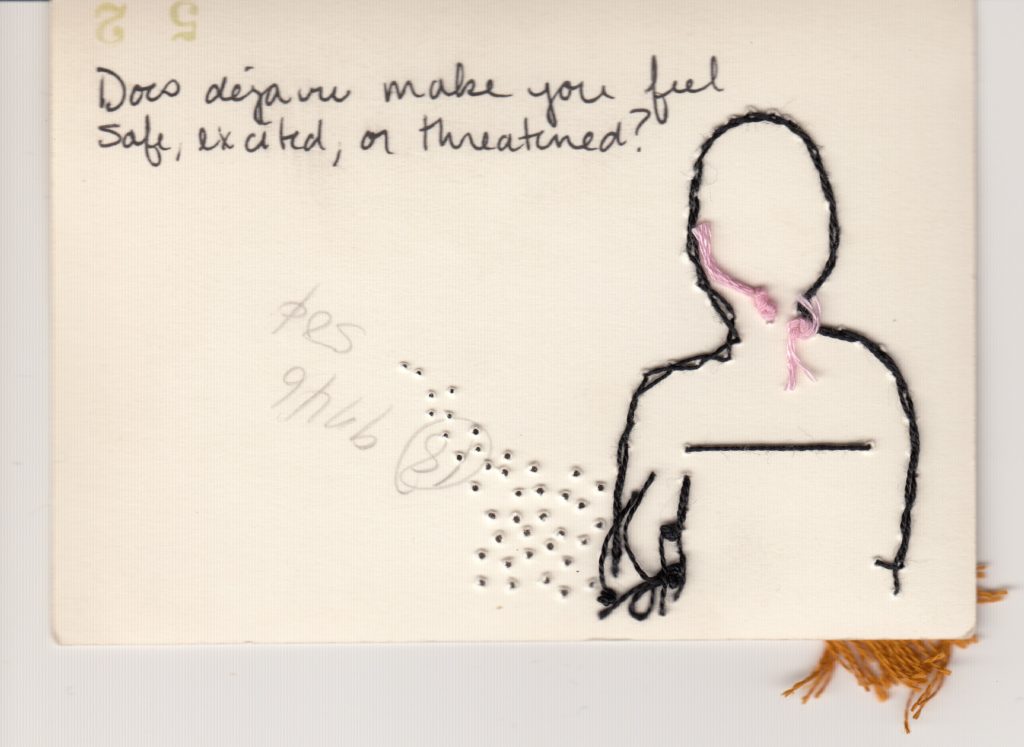

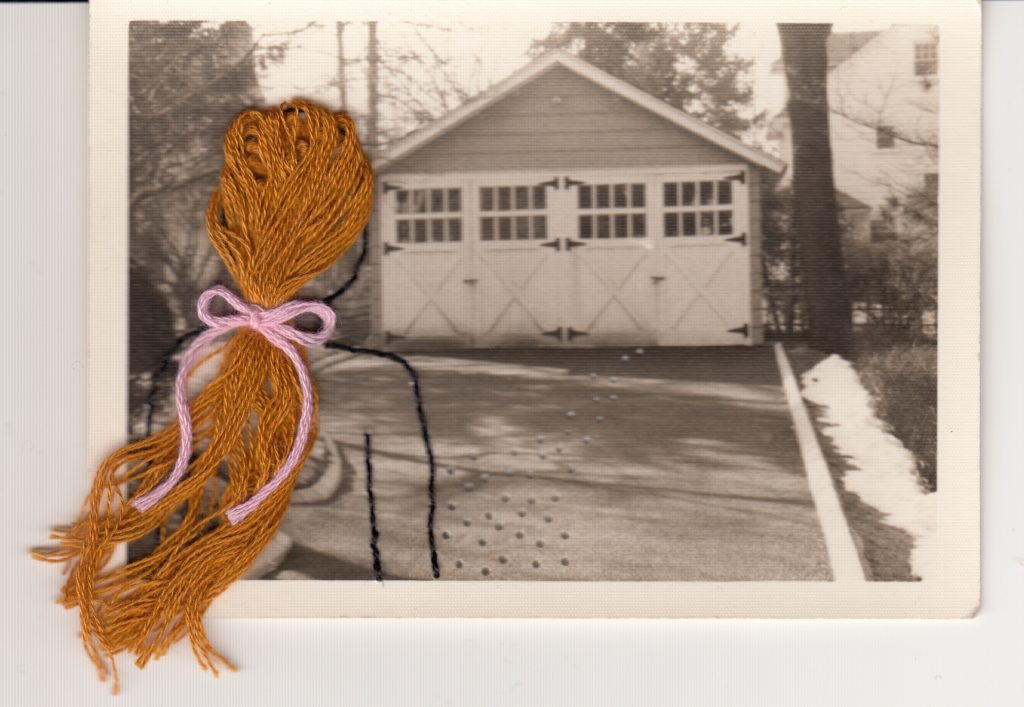

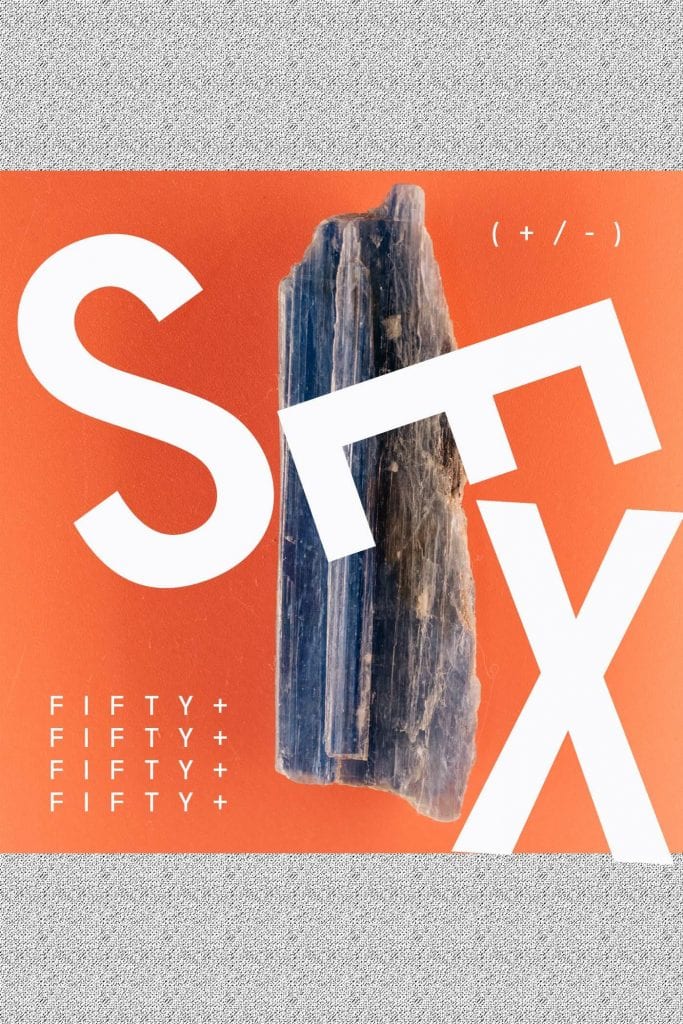

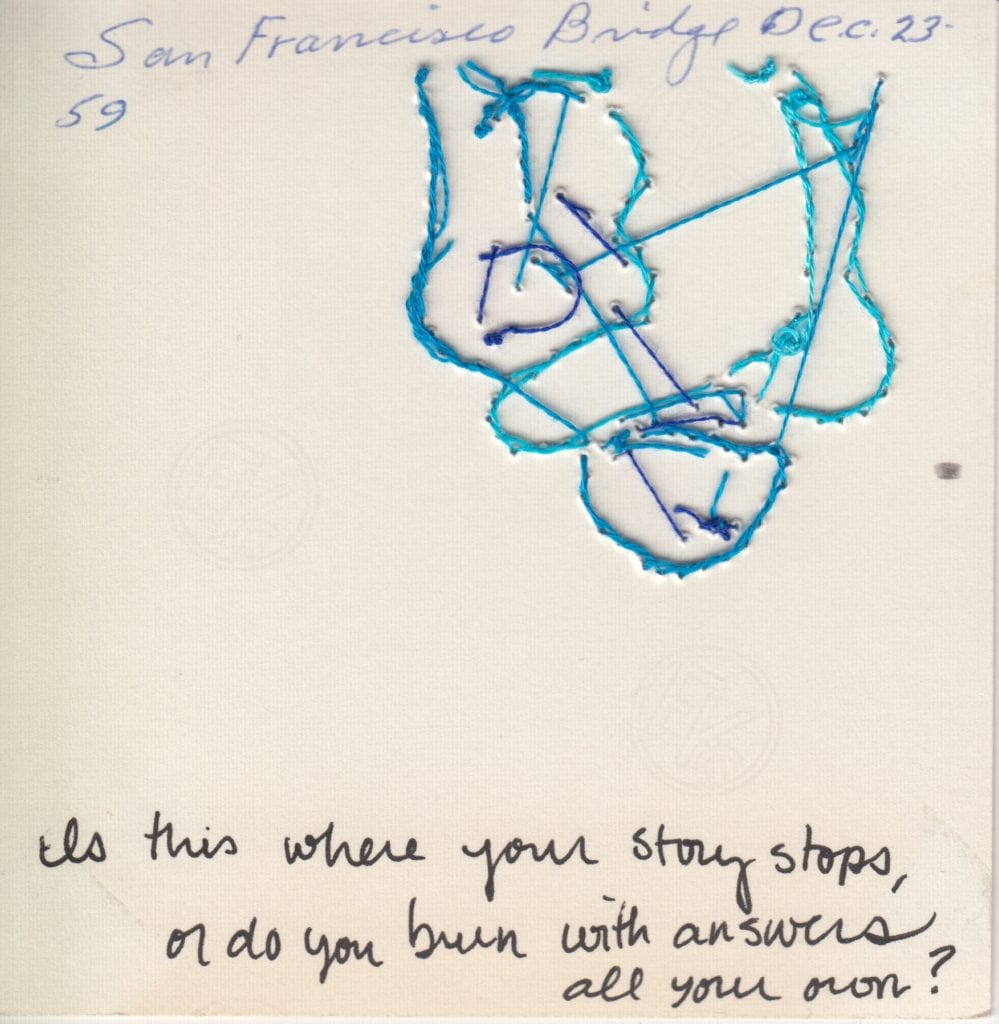

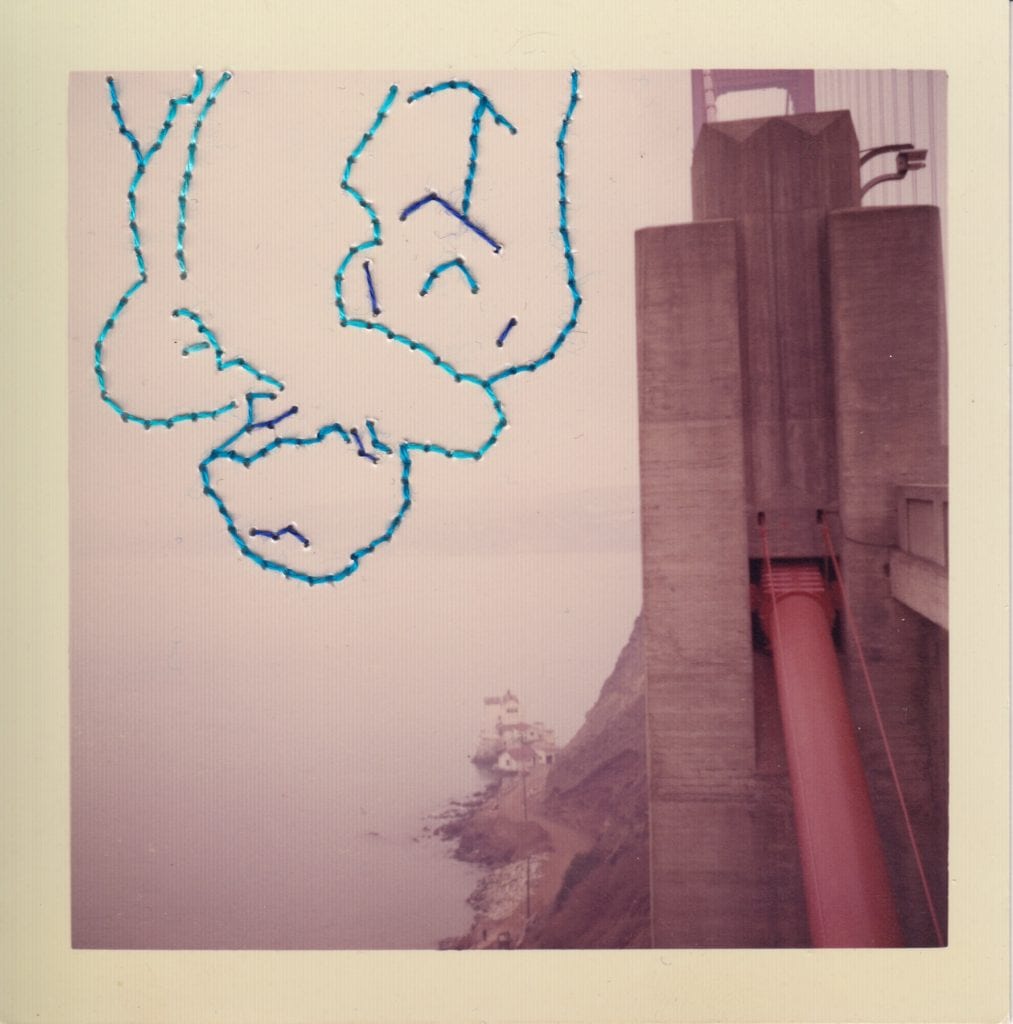

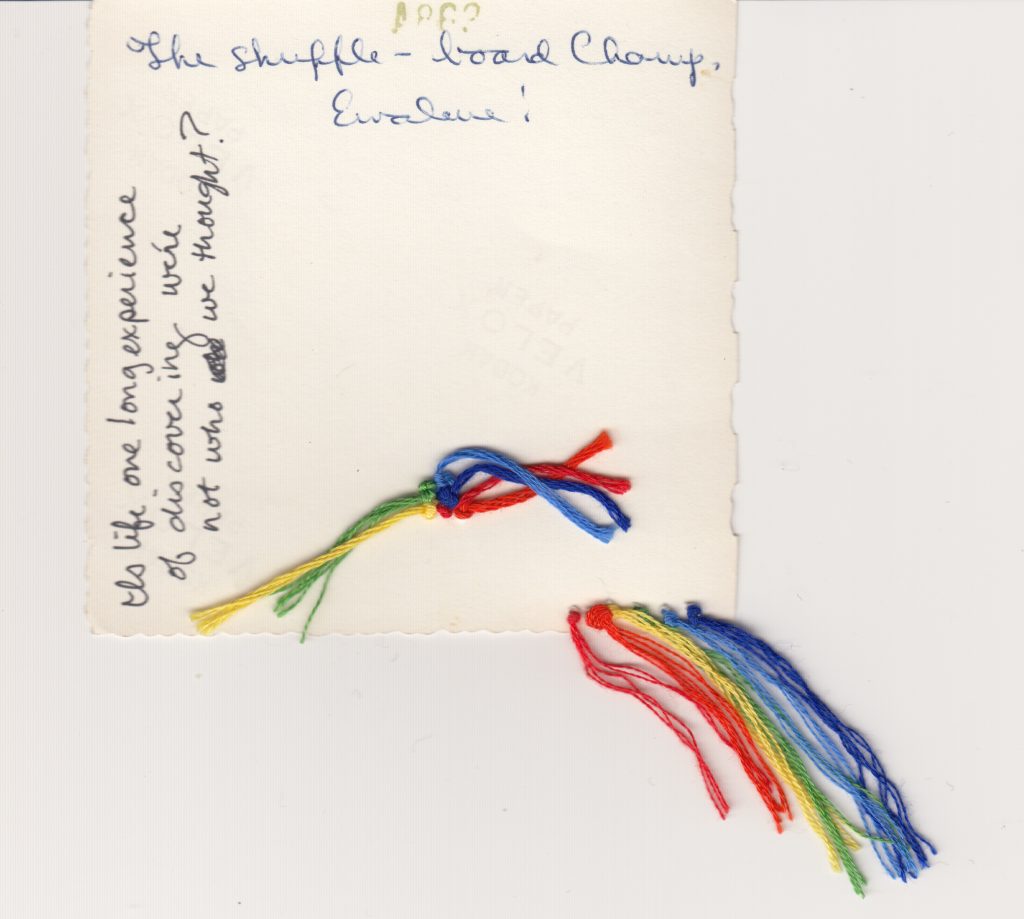

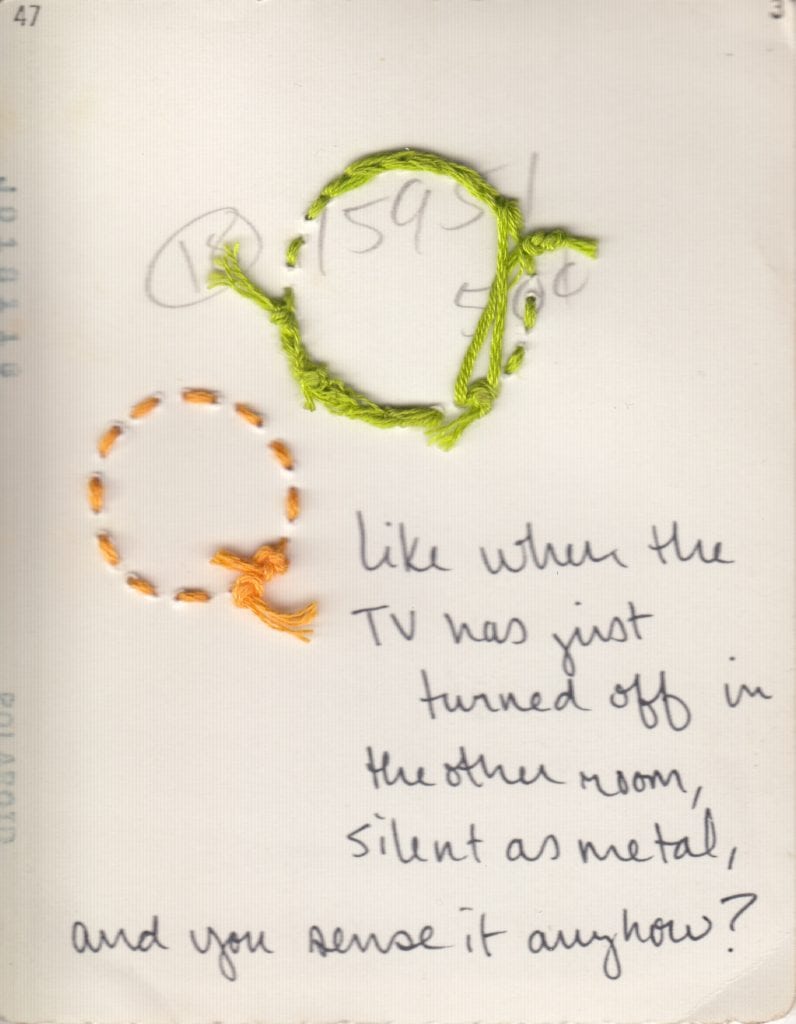

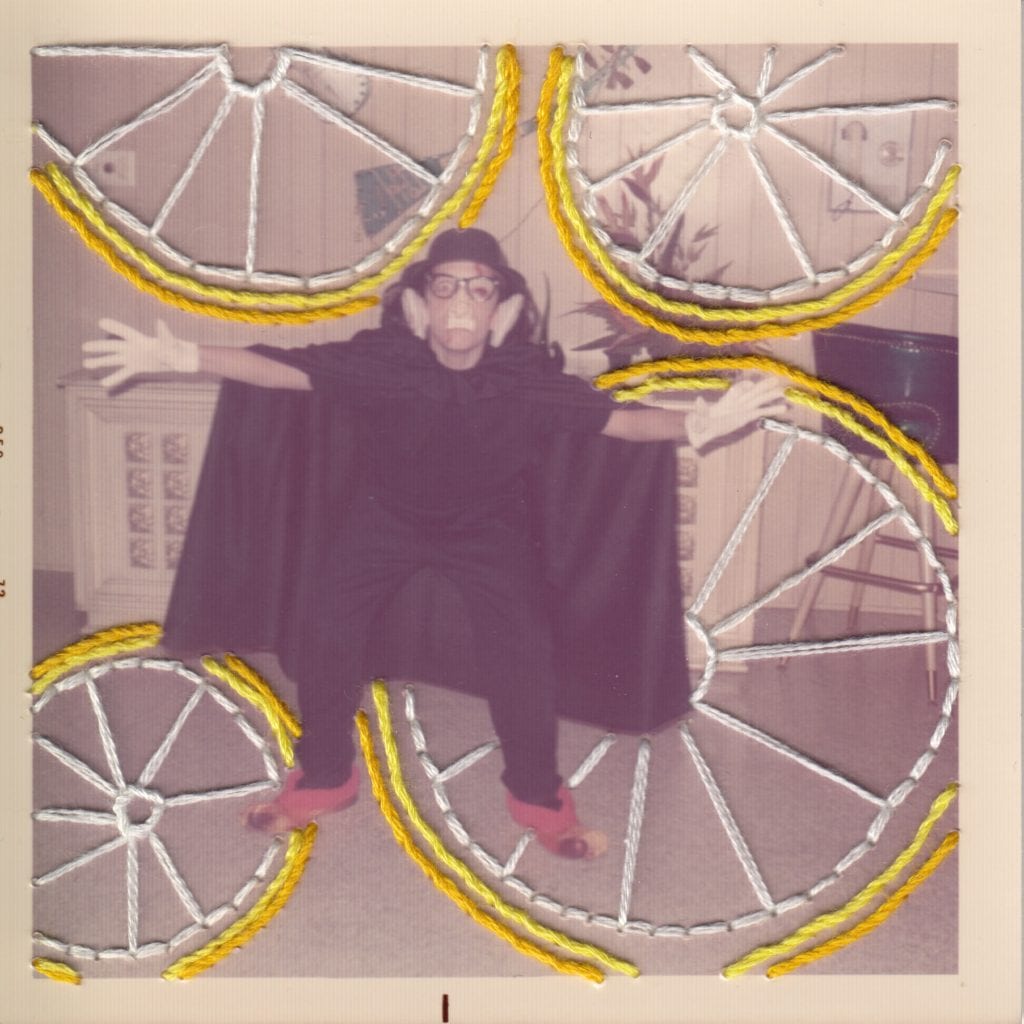

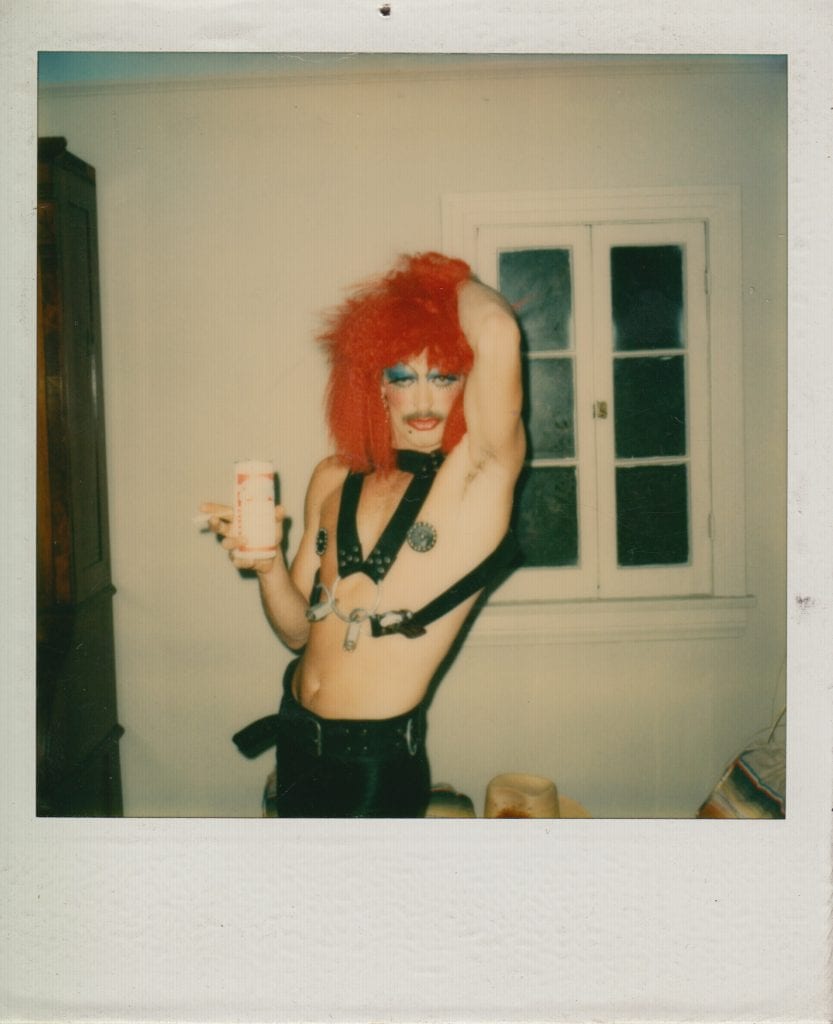

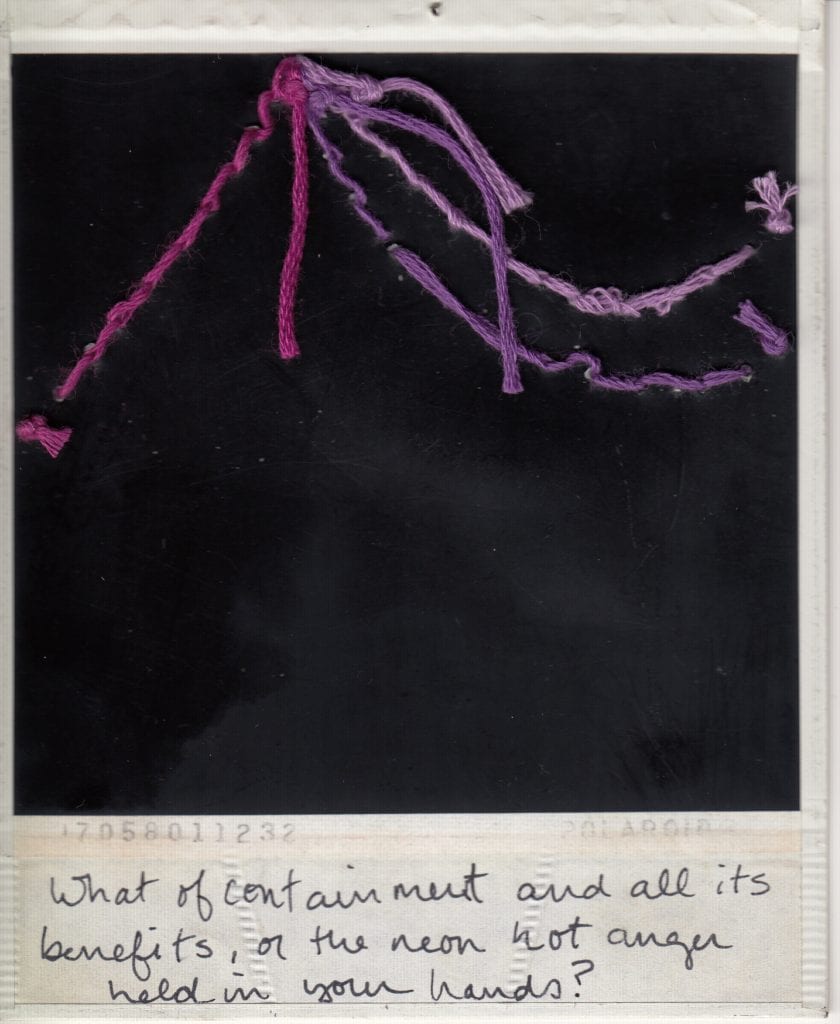

Related: Below are some videos I made for my gallery’s Instagram stories this month. I ~authorized~ myself to learn how to animate my work and post it even if I don’t think it’s perfect yet. Can’t wait to see what February brings. Stay healthy, friends.